TODAY

Washington faces a flood of administrative demands. He writes to Colonel Alexander McDougall in New York. The recent capture of the British ordnance ship Nancy has supplied his army with shells and shot, but he still lacks cannon. He urges McDougall to expedite the promised shipment of “twelve good iron four-pounders.”

To John Hancock, Washington reports the capture of the ship Concord and asks Congress how to handle its cargo of coal and goods. Recruiting is slow, supplies thin, gunpowder dangerously low. Washington holds this fragile army together.

In his General Orders, Washington expresses “surprise and astonishment” that several Connecticut soldiers could abandon their duty so close to the end of their enlistment. He sends an express to Governor Jonathan Trumbull with their names so they can be punished “in a manner suited to the ignominy of their behavior.”

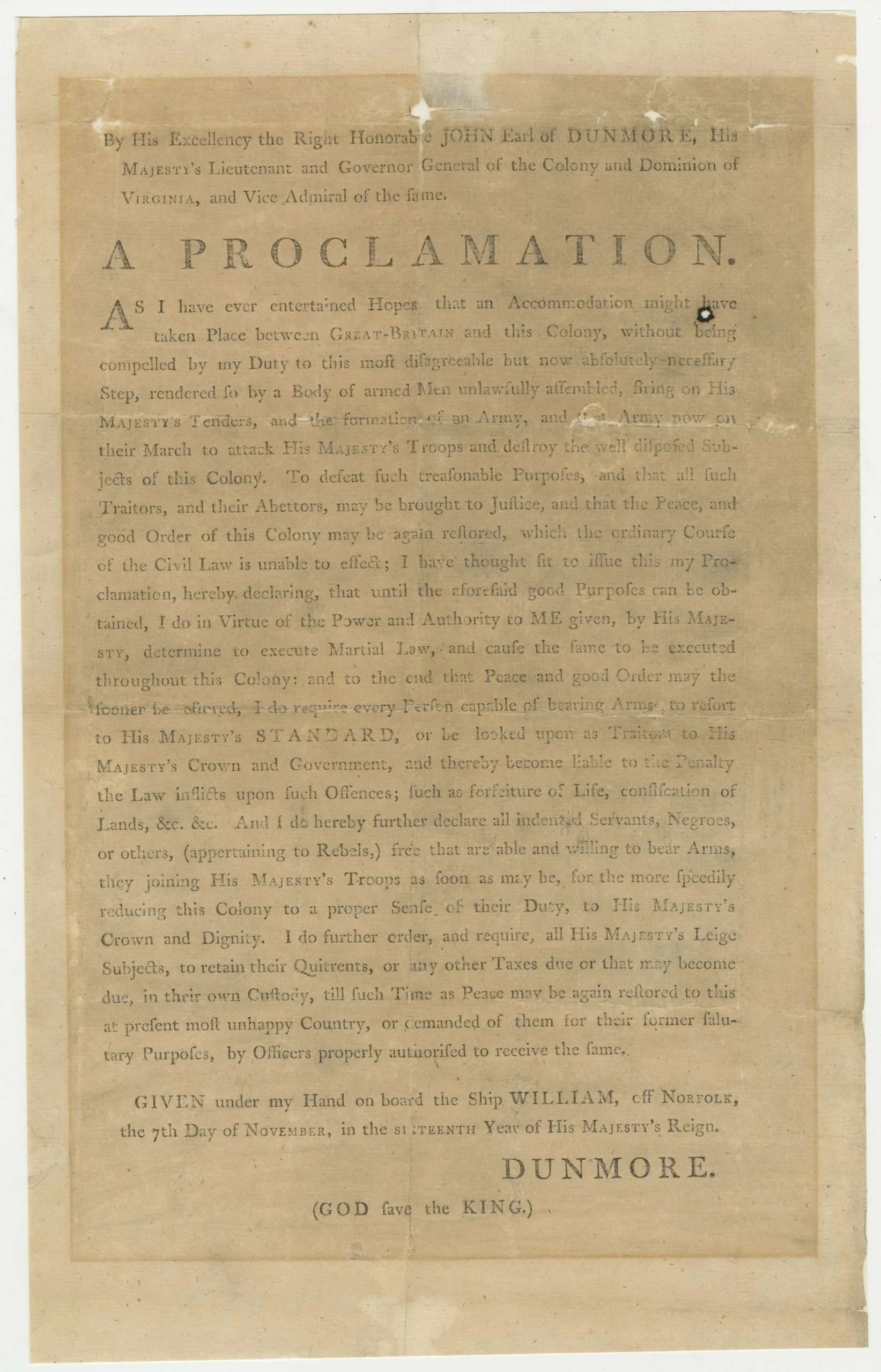

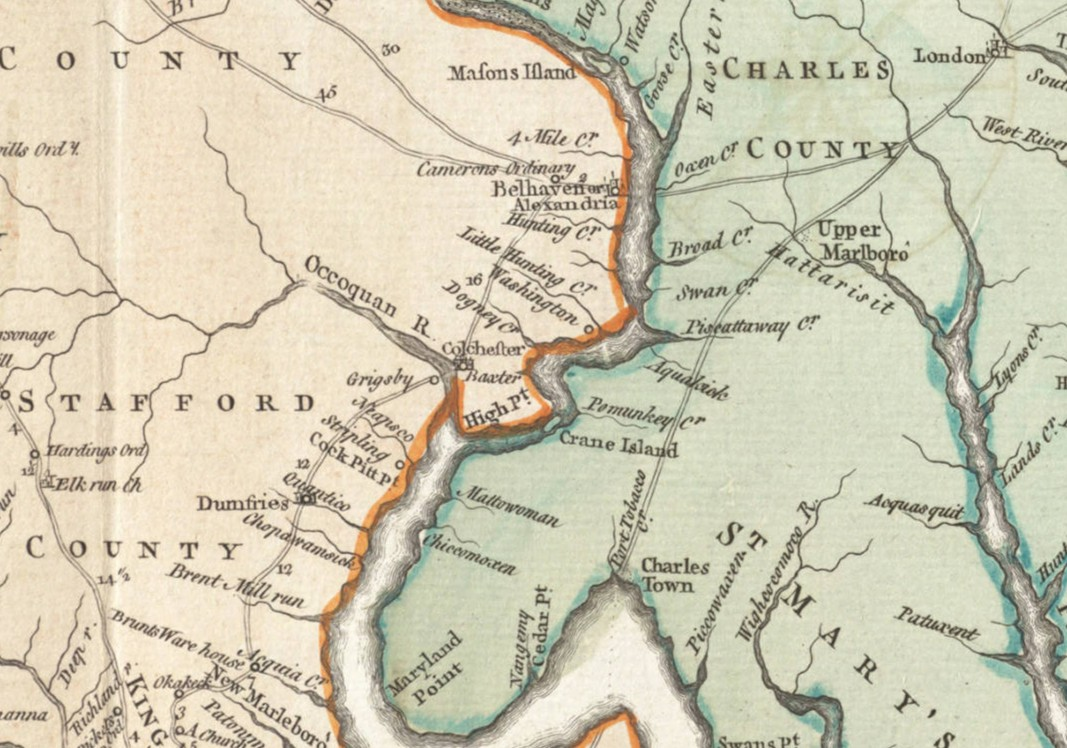

From Mount Vernon, his cousin Lund Washington reports that Lord Dunmore’s proclamation promising freedom to enslaved people of rebel masters has unsettled Virginia. “Liberty is sweet,” Lund observes, fearing the temptation it offers.

Washington struggles to maintain discipline as Connecticut troops threaten to abandon camp before their replacements arrive. Some men flee with arms; others are caught and returned. In a letter to Governor Jonathan Trumbull, he condemns their “extraordinary and reprehensible conduct” and wonders if examples should be made to preserve order.

John Hancock writes with urgent news: Congress authorizes new funds, commissions Henry Knox as colonel of artillery, and reports Lord Dunmore’s alarming proclamation offering freedom to enslaved Virginians.

Washington issues orders: Too many soldiers have been straying from their posts, ignoring duty, and leaving the lines exposed to surprise attack. Washington warns of “fatal consequences” when men are “scattered and remote from their posts.” From now on, no officer or soldier may leave his station without written permission.

General Israel Putnam writes Washington, describing how he and Colonel Henry Babcock have quelled a dangerous mutiny among the Connecticut troops. Praising Babcock’s courage and experience, Putnam recommends him for promotion to brigadier general.

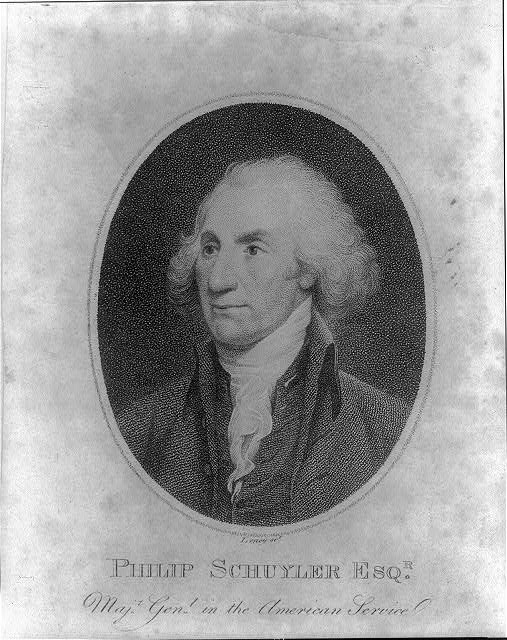

In a letter to General Philip Schuyler, Washington complains that, despite his best efforts, “No Troops were ever better provided or higher paid, yet their Backwardness to inlist for another Year is amazing: It grieves me to see so little of that patriotick Spirit, which I was taught to believe was Characteristick of this people.”

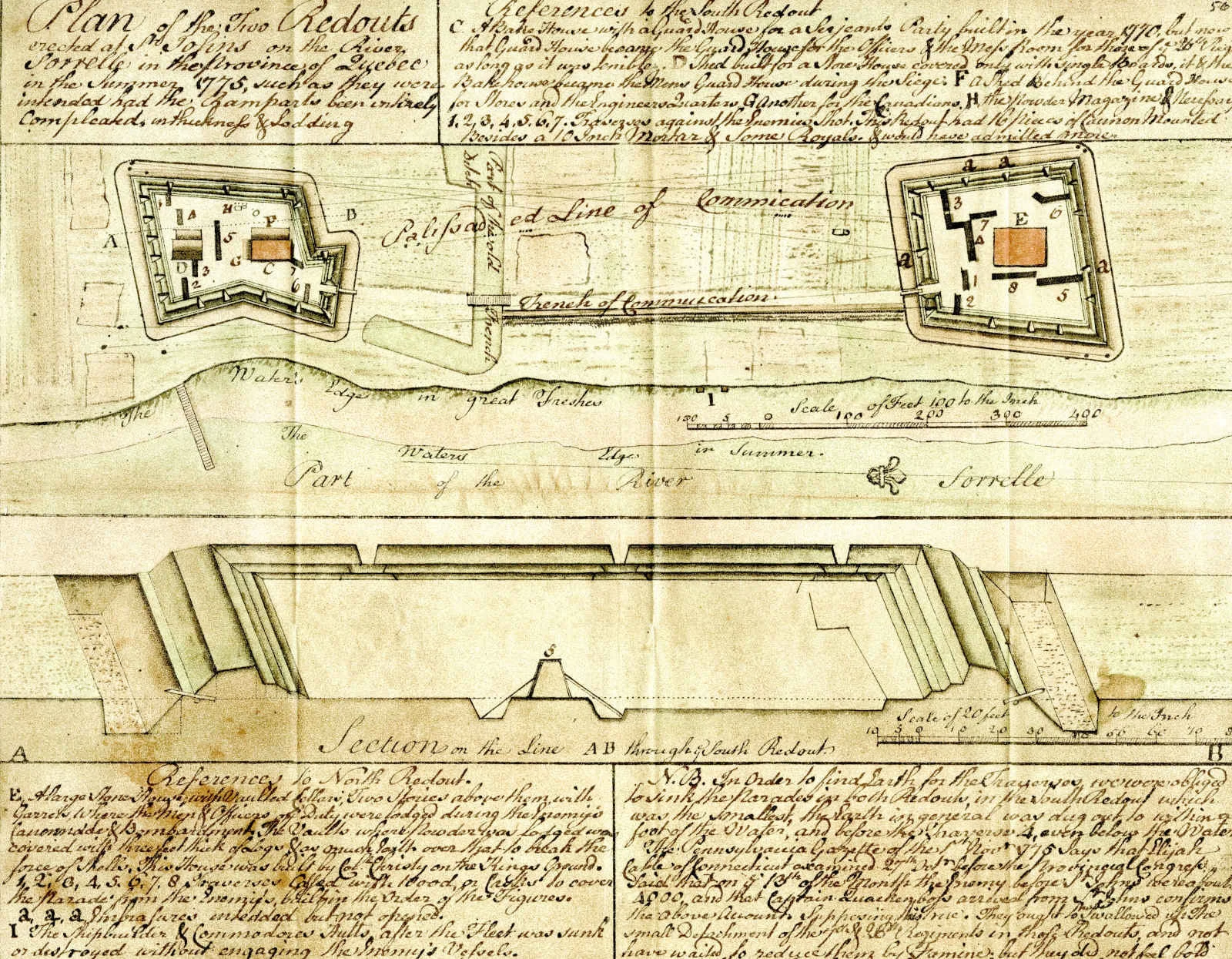

In instructions to John Grizzage Frazer, Washington commands the urgent hiring—or if need be, impressment—of teams and wagons to haul boards, planks, and hay from towns along the Merrimack River to Winter and Prospect Hills, where redoubts rise against British fire.

From Cambridge, Washington writes to the Massachusetts General Court, warning that furloughs granted to encourage reenlistment have reduced his ranks by 1,500 men. He also chastises them for paying troops by the lunar month—28 days—rather than the calendar month established by Congress.

Merchant-agent William Watson writes from Plymouth that the crew of the brigantine Washington—soldiers turned sailors—have mutinied, refusing duty because they enlisted for the army, not the navy. His letter underscores the fragility of the fledgling navy.

In his General Orders, Washington announces Montreal’s surrender and credits “divine providence,” urging every American to exert his utmost and show no backwardness in the public cause.

He scribbles a quick note to Captain George Baylor, who is on the road to meet Martha: hire extra horses if needed, send word before reaching town, and keep an expense account. His longest letter goes to aide-de-camp Joseph Reed. He misses Reed’s ready pen and presses for his return, then pours out the day’s anxieties.

An Express last Night from General Montgomery, brings the joyful tidings of the Surrender of the City of Montreal, to the Continental Arms—The General hopes such frequent Favors from divine providence will animate every American to continue, to exert his utmost, in the defence of the Liberties of his Country, as it would now be the basest ingratitude to the Almighty, and to their Country, to shew any the least backwardness in the public cause.

- Washington's General Orders

Washington writes his aide-de-camp Joseph Reed, recounting how, five nights earlier, his troops quietly occupied Cobble Hill, a key rise between the American and British lines. Washington reports that the army has worked on fortifying the position ever since.

In New York, Colonel Henry Knox writes after meeting with local leaders. The officials have promised to send 12 iron cannons, ammunition, and even two fine brass six-pounders. He vows to set out immediately for Fort Ticonderoga to retrieve the cannon needed to drive the British from Boston.

Washington receives a grim report from Lt. Colonel Loammi Baldwin at Chelsea. Baldwin describes refugees escaping Boston “in a most shocking condition,” some dying on the beach.

Washington writes to his cousin and estate manager, Lund Washington. “It is the greatest—indeed the only comfortable reflection I enjoy … to think that my business is in the hands of a person in whose Integrity I have not a doubt.” He instructs Lund to sell rum, secure his wine, give food and charity to the poor, and, if British ships approach the Potomac, defend the estate only when safe to do so.

In the day’s orders, the parole is “Hampden” and the countersign “Pym.” A parole and countersign serve as daily passwords, exchanged between sentries and officers to ensure security. Washington’s choice, names of English patriots who resisted royal tyranny, reminds his soldiers that their own rebellion follows in that tradition.

Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island reports to Washington his assembly has seized Tory estates and decreed death and confiscation for anyone supplying the enemy.

Washington writes instructions for Aaron Willard and Moses Child, two men chosen for a secret mission to Nova Scotia. Their task, ordered by Congress, is to discover the colony’s sympathies and to assess its fortifications, ships, and stores.

Far away at Mount Vernon, Lund Washington writes to his cousin. His letter paints a vivid picture of homefront burdens: crumbling fences, freezing weather, and mounting repairs. He ends with word of Lord Dunmore’s victory over Virginia militia.

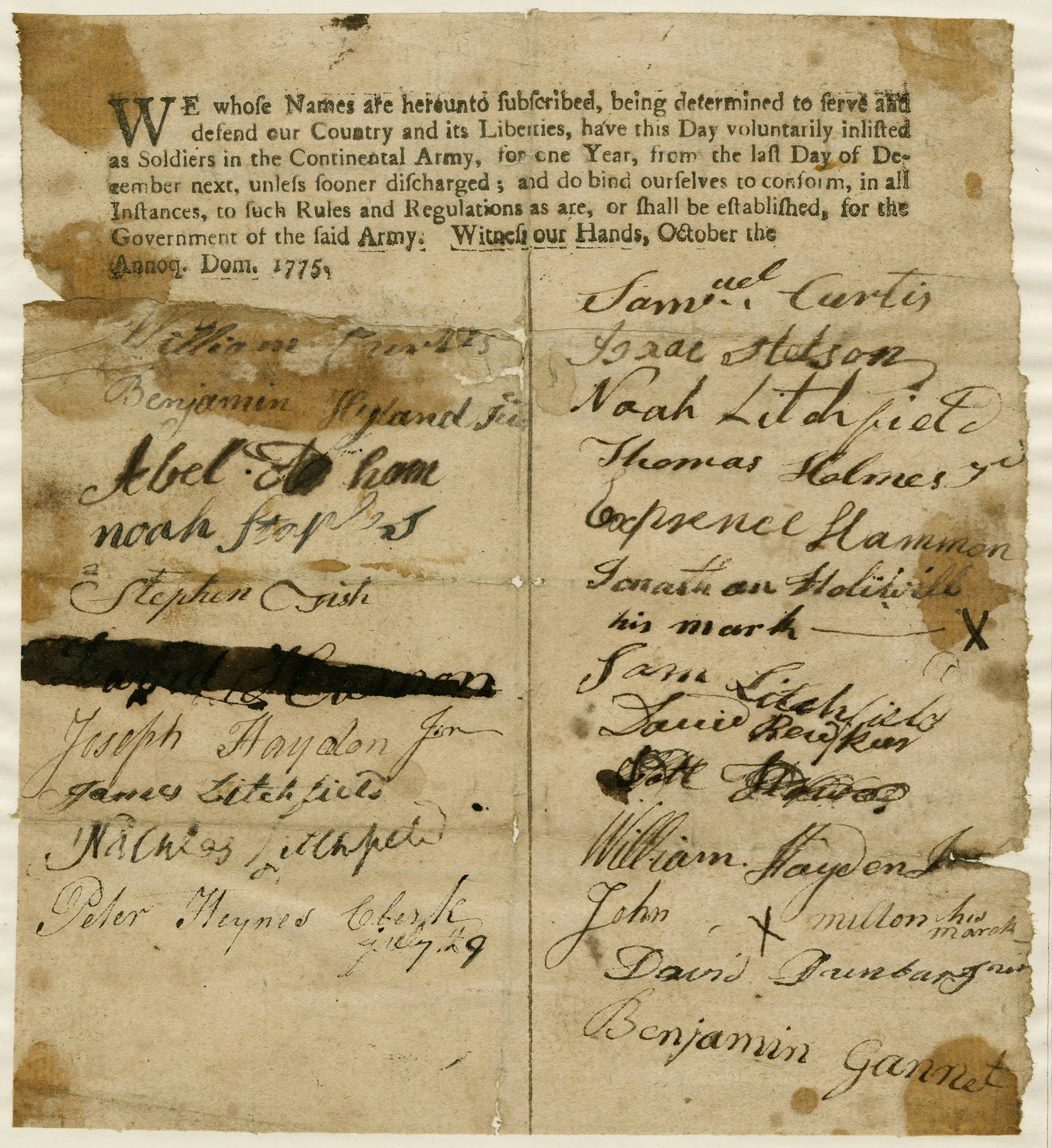

With winter approaching, Washington knows his army could dissolve. From his Cambridge headquarters, he issues orders to strengthen the army as enlistments near expiration. He authorizes colonels to advance two months’ pay to recruiting officers and ensures new recruits receive pay and subsistence allowances immediately.

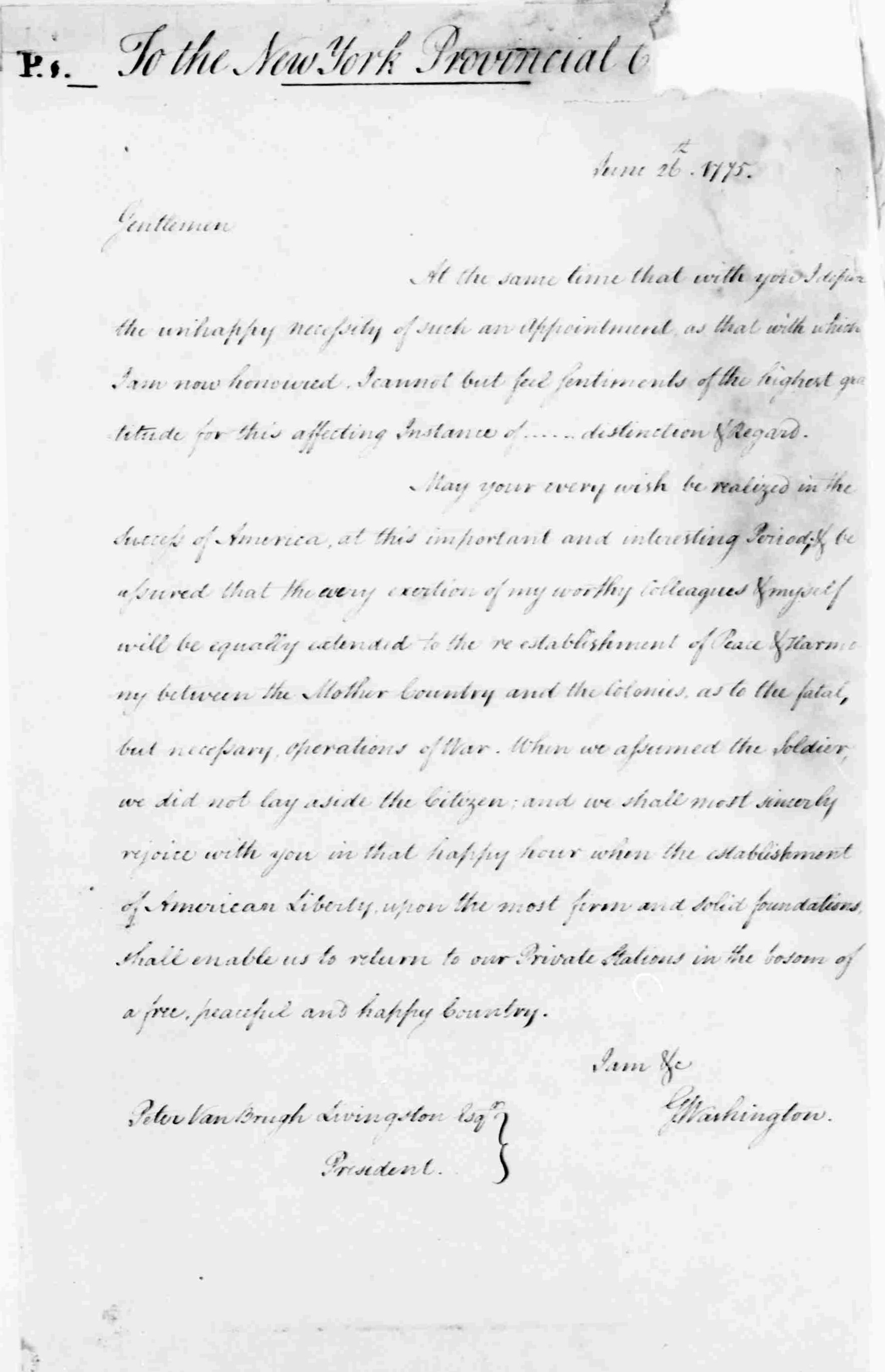

Washington insists recruits be sent promptly to camp and recalls ineffective recruiters. To preserve resources, he directs officers to appoint three-man commissions to inspect and record arms returned by discharged soldiers.

Washington spends another day shaping his army. He rebukes first lieutenants who believe they might take over their captains’ commands if they can recruit faster, warning that anyone acting from such motives will be dismissed “with disgrace.” Washington directs officers to clean and inspect soldiers’ new winter barracks and ensures tents are collected and repaired.

Meanwhile, General Philip Schuyler writes to Washington from Ticonderoga, enclosing letters from Benedict Arnold describing his near-impossible march through the Maine wilderness toward Quebec.

Two young soldiers have been found guilty of abandoning their posts while on duty—an offense that could have cost them their lives. A court-martial has sentenced them to 15 lashes each, but Washington, noting their youth and inexperience, grants them mercy. He warns, however, that such leniency will not be repeated.

John Brown of Providence writes Washington offering “one ton of good pistol powder” at six shillings per pound. Powder is scarce, vital for survival, and even at that high price, Washington will agree to buy it.

From Cambridge, Washington writes Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, his trusted secretary and confidant. He updates Reed on pressing matters: the army’s dire lack of pay, Congress’s slow response, and his appeal for one month’s advanced wages to encourage soldiers to reenlist. Washington mentions Henry Knox’s mission to fetch artillery from Ticonderoga, noting the army’s shortage of guns and flints.

He thanks Reed for news of Martha, who is traveling north to join him, and asks Reed to advise her route, “by all means avoiding New York.”

In a letter to John Hancock, Washington warns that raising two marine battalions from his own ranks would “entirely derange what has been done,” breaking the fragile organization he has built. Supplies are scarce; barracks unfinished; men discouraged by lack of pay and wood.

In British-held Boston, imprisoned Patriot James Lovell writes Washington. He has been told he will only be freed if the Americans release Loyalist Colonel Skene. Lovell refuses such “disgraceful” terms but appeals to Washington’s compassion, fearing his wife will starve in the coming winter.

Personally a Stranger to you, my Sufferings have yet affected your benevolent Mind; and your Exertions in my Favor have made so deep an Impression upon my grateful Heart as will remain till the Period of my latest Breath.

- James Lovell to George Washington

Washington instructs the commissary general to collect all bullock horns from cattle slaughtered for army provisions. The horns are to be crafted into powder horns—essential tools for soldiers who must carry dry gunpowder.

He then shares a proclamation from the Massachusetts General Court, declaring Thursday, November 23, a day of public thanksgiving. Washington commands that every officer and soldier observe it with “unfeigned devotion”—a solemn pause in the midst of war to pray for peace and liberty.

In his General Orders, Washington announces that Congress has increased officers’ pay, intended to reward their service and encourage renewed recruitment. He also calls a meeting to establish uniform standards, knowing that appearance strengthens morale as much as muskets.

Washington also writes to Major General Artemas Ward. With the bay between Cambridge and Boston soon to freeze, he warns that General Howe may try to escape the city once the ice allows movement. Perhaps by surprise, he suggests, the Americans might even seize the British fort in Boston Harbor.

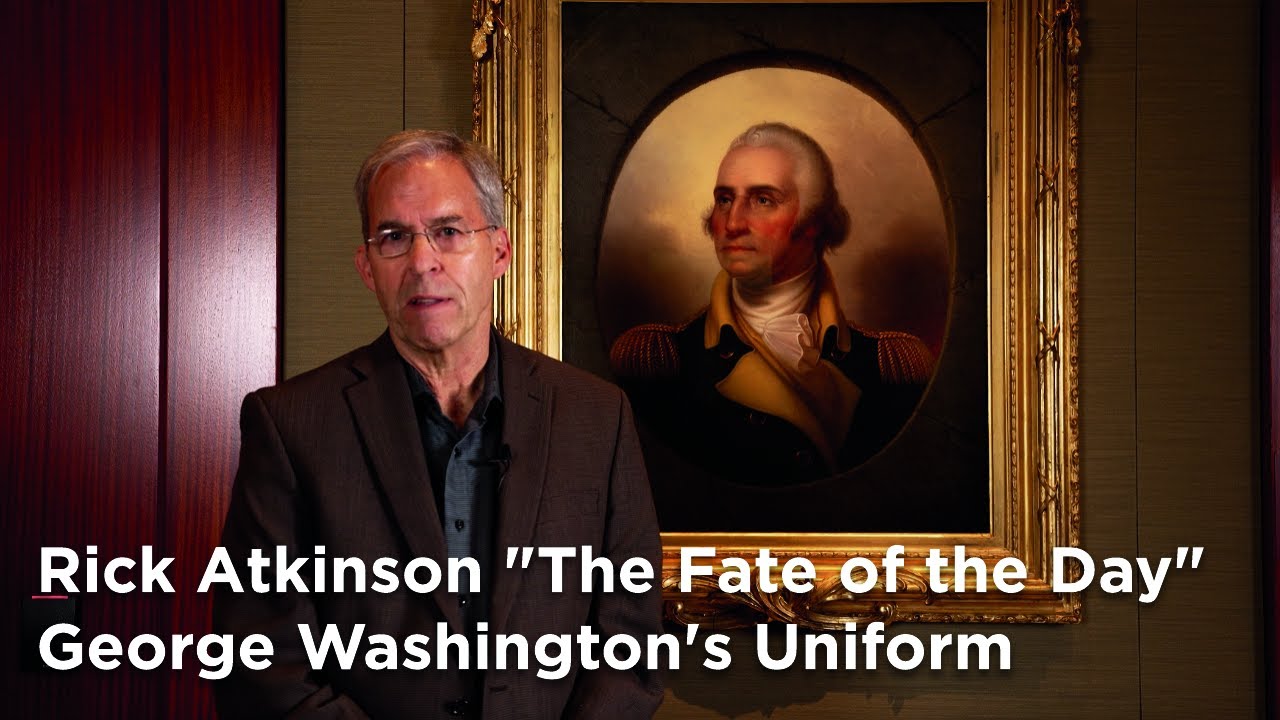

Washington drafts consequential instructions for Colonel Henry Knox, commissioning him to travel first to New York and then to Ticonderoga, Crown Point, or St. Johns to secure desperately needed artillery and ammunition.

He gives Knox $1,000 in funds and orders him to use “no trouble or expence” spared in completing the mission. This moment marks the beginning of Knox’s legendary “Noble Train of Artillery,” which will eventually bring the captured guns of Ticonderoga to Boston.

You are immediately to examine into the state of the Artillery of this army & take an account of the Cannon, Mortars, Shels, Lead & ammunition that are wanting; When you have done that, you are to proceed in the most expeditious manner to New York.

- George Washington to Colonel Henry Knox

Washington reports the verdicts of several courts martial — acquittals, fines, lashings, and dismissals — and gives his approval. Mutiny, drunkenness, and insubordination will not threaten the army’s unity.

But discipline extends beyond the camp. Dr. Benjamin Church, once a trusted physician and patriot, has been exposed as a British spy. Congress has decreed that Church be held in strict confinement and denied writing materials. Washington writes to Governor Jonathan Trumbull, forwarding these orders and sending Church under armed guard to Connecticut.

Learning of the surrender of Fort St. John in Canada, Washington calls on his soldiers to show gratitude to Providence for “thus favouring the Cause of Freedom and America.” Meanwhile, complaints against the commissary general and the unregulated sale of liquor among the ranks draw his sharp attention; he promises investigation and tighter controls.

Lund Washington writes from Mount Vernon, reporting on crops, rain-soaked fields, and ongoing repairs to chimneys and roofs. He proposes manufacturing saltpeter for gunpowder.

In today’s General Orders, Washington instructs all regimental commanders to promptly meet with the quartermaster general to finalize their troops’ uniforms. Each regiment’s buttons must be properly numbered for identification.

Far to the north, outside of Quebec, Benedict Arnold writes Washington. Tonight, he plans to take 40 canoes across the icy St. Lawrence River, slipping past the British sloop Hunter and the frigate Lizard. The goal is a surprise attack on Quebec.

Washington issues orders to organize the Continental Army for a new year. He directs each colonel to collect printed enlistment forms for their officers, and he specifies pay rates, clothing deductions, and incentives—two dollars for any soldier who brings his own blanket.

From Mount Vernon, Lund Washington writes to his cousin with domestic updates. He plans to defend Mount Vernon should Lord Dunmore’s forces come upriver, vowing to “destroy a few of his men before the house is fired.”

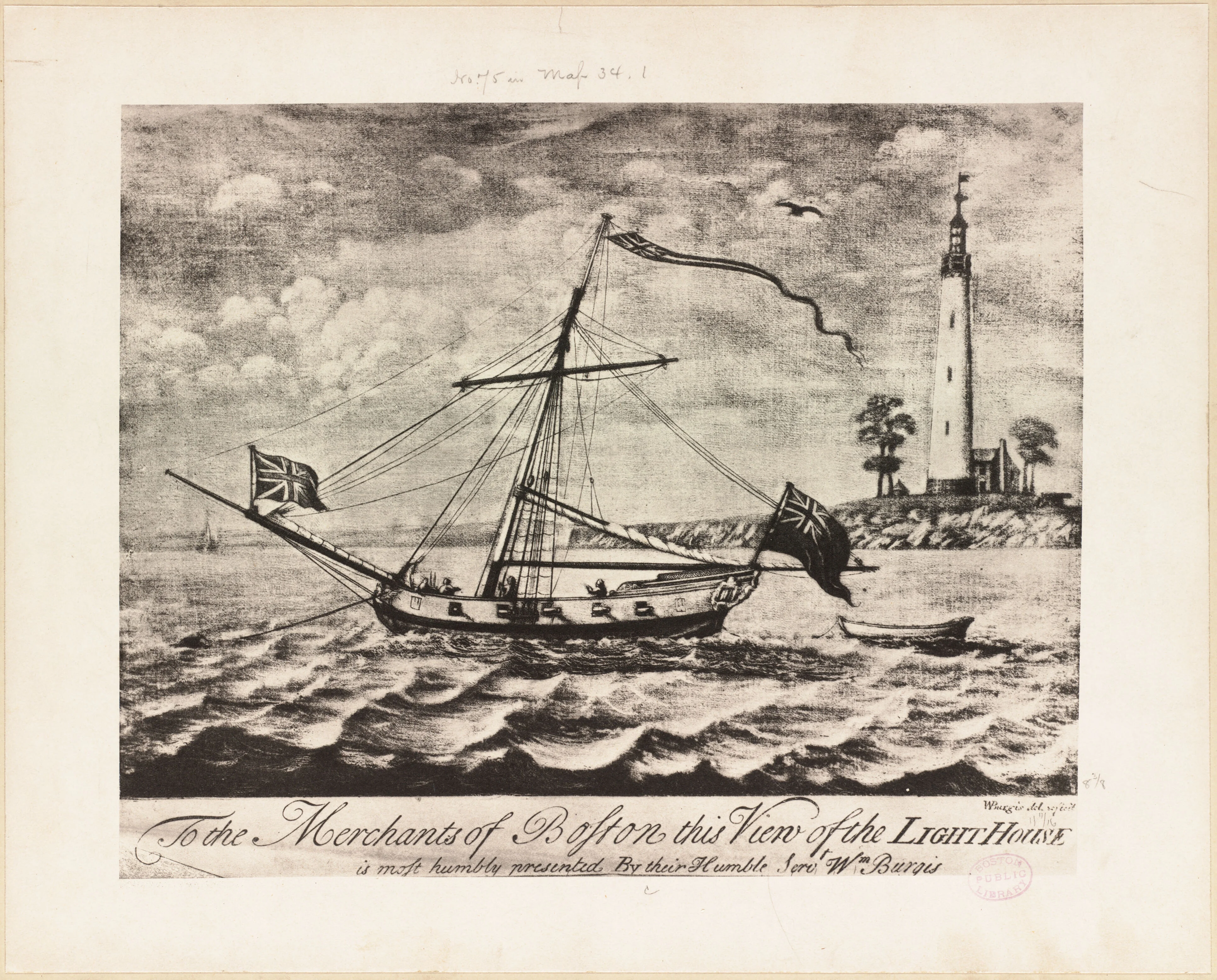

Washington writes to John Hancock, reporting the capture of the British sloop Ranger by Captain John Manley’s schooner Lee. The vessel, once a British prize, is now in American hands—an early naval victory.

Yet Washington’s tone is measured, not triumphant. He urges Congress to establish a formal system for judging such captures, warning that he cannot spare time from military affairs to manage legal disputes.

Should not a Court be established by Authority of Congress to take Cognizance of Prizes made by the Continental vessells? whatever the mode is which they are pleased to adopt, there is an absolute necessity of its being Speedily determind on, for I Cannot Spare time from military affairs, to give proper attention to these Matters…

- George Washington to John Hancock

In response to a skirmish at Letchmore’s Point yesterday, Washington commends Colonel William Thompson and his men for wading through icy water to engage the British, praising their courage. But he also warns that some soldiers hesitated to cross the causeway and may face consequences.

Meanwhile, John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, forwards Washington newly passed resolutions—among them, the creation of two battalions of Marines and plans for a potential expedition to Nova Scotia.

Washington writes to James Warren of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, alarmed by reports that General Howe in Boston is allowing civilians to leave the city. Washington fears these refugees could carry smallpox into the American camps, where the disease could devastate his troops.

Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos, who has abandoned Benedict Arnold’s expedition to Quebec, writes Washington to explain that hunger and exhaustion forced his division to turn back after reaching the Dead River in Maine. He defends his choice to save the lives of his men, many of whom were starving.

In a letter to John Hancock, Washington dismisses Captain Macpherson’s costly and impractical plan to destroy the British fleet in Boston. He outlines several maritime captures, ships wrecked or seized, and urges Congress to settle the growing confusion over seized enemy property.

Washington also writes Joseph Reed about efforts to reorganize the army for 1776. Fierce regionalism among the colonies is stalling progress—Connecticut refuses to accept Massachusetts officers, and New Hampshire protests the loss of its experienced men. “We are nearly as we begun,” he writes wearily.

Major General Philip Schuyler writes Washington with triumphant news: Fort St. Jean has fallen. Schuyler forwards General Richard Montgomery’s report that the British garrison surrendered on November 3. “I beg leave to congratulate you on this happy event,” Schuyler writes.

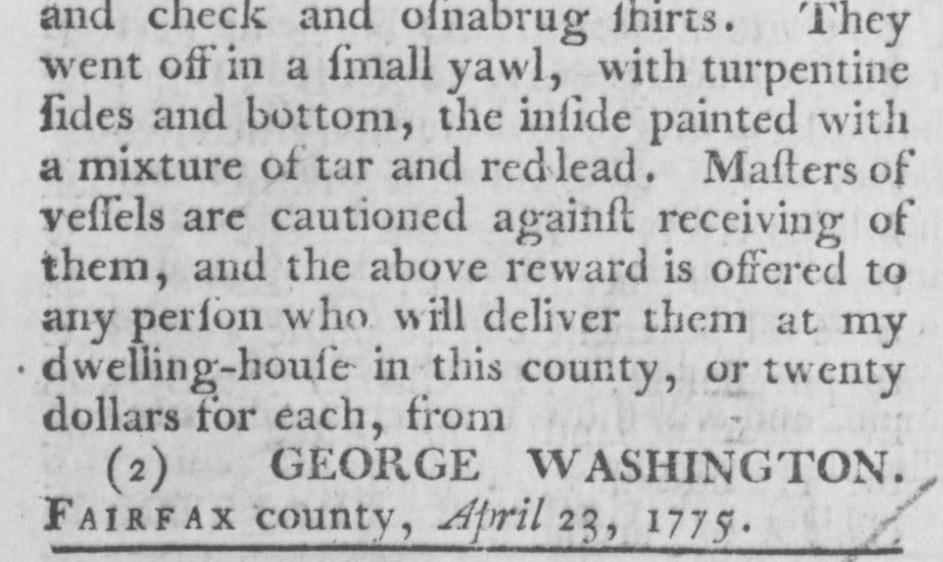

Meanwhile, Virginia’s royal governor Lord Dunmore drafts an incendiary proclamation: freedom for enslaved people and indentured servants who will bear arms for the Crown against rebel masters. Though not yet published, the proclamation will signify a dangerous escalation for many Patriot leaders.

In today’s orders, Washington addresses a troubling trend: soldiers cutting down trees for firewood without permission. Though the “disagreeableness of the weather” and a scarcity of wood tempt leniency, Washington reaffirms the need for discipline.

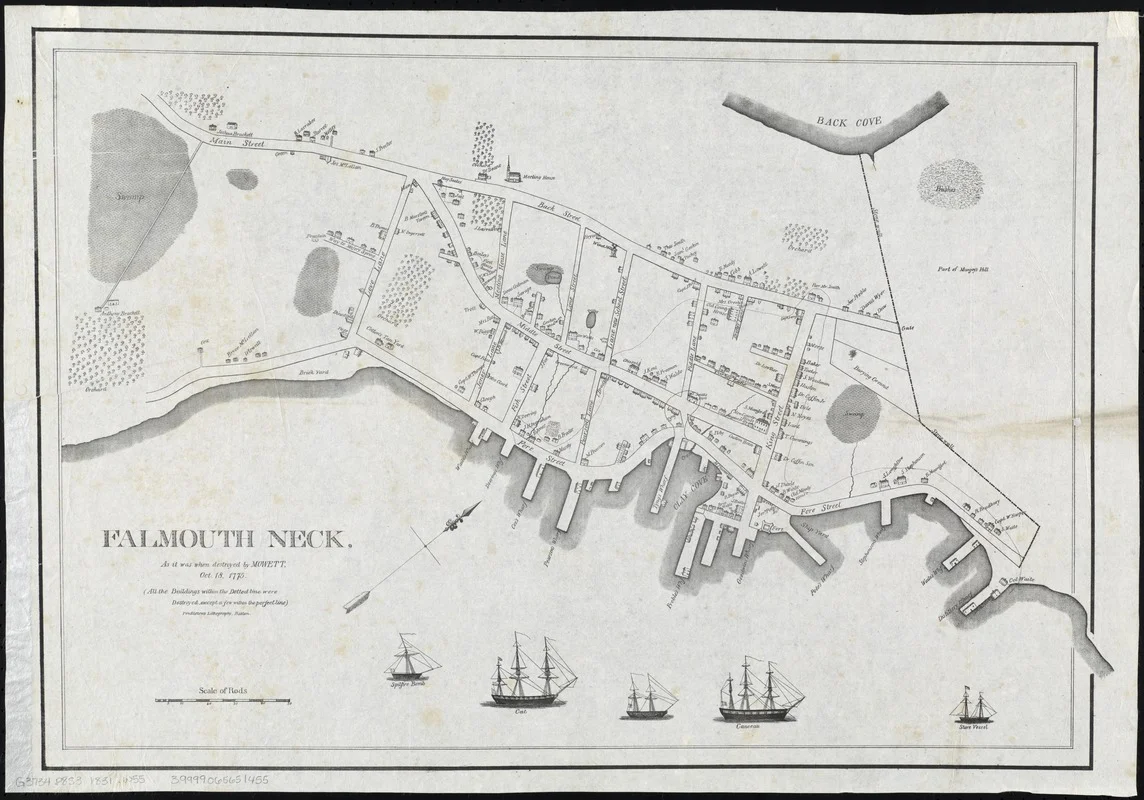

He turns his attention to Falmouth, Maine, still reeling from the British naval bombardment on October 18. He writes to Enoch Moody, chairman of the town’s committee, offering sympathy but explaining that he cannot send military aid—the main army must remain intact.

Washington hears that some soldiers plan to mark Guy Fawkes Day by burning an effigy of the Pope—an anti-Catholic ritual. Outraged, Washington issues orders condemning the plan as “ridiculous and childish.” He reminds his army that the American cause depends on winning over French Canadian Catholics.

Washington's cousin and estate manager, Lund Washington, writes from Mount Vernon. He reports that Martha plans to begin her journey north soon. He worries her delay may make for “a very disagreeable journey” in cold weather.

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d, for the observance of that ridiculous and childish Custom of burning the Effigy of the pope—He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers, in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship & alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered, or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.

- George Washington in his General Orders

Washington responds to a letter from Josiah Quincy, a respected Boston patriot who has proposed placing artillery on Long Island in Boston Harbor to blockade British ships. Washington points out a harsh truth: The army lacks the cannon and powder to execute such a plan.

Meanwhile, in Beverly, Massachusetts, merchant William Bartlett seizes a rare opportunity. A storm has driven the British supply sloop North Britain into harbor, damaged and vulnerable. Bartlett helps organize its capture and immediately reports to Washington, requesting guidance.

From Providence, merchant John Brown writes Washington with news. A vessel from Surinam has arrived carrying casks of gunpowder. Unsure whether to send it to the army or sell it locally, Brown offers to spare a portion for the Continental Army, though the Rhode Island Assembly may soon purchase it for coastal defense.

Far to the north, American forces under General Richard Montgomery achieve a major victory: Fort St. Jean surrenders after a six-week siege. This success opens the path to Montreal and marks a turning point in the invasion of Canada.

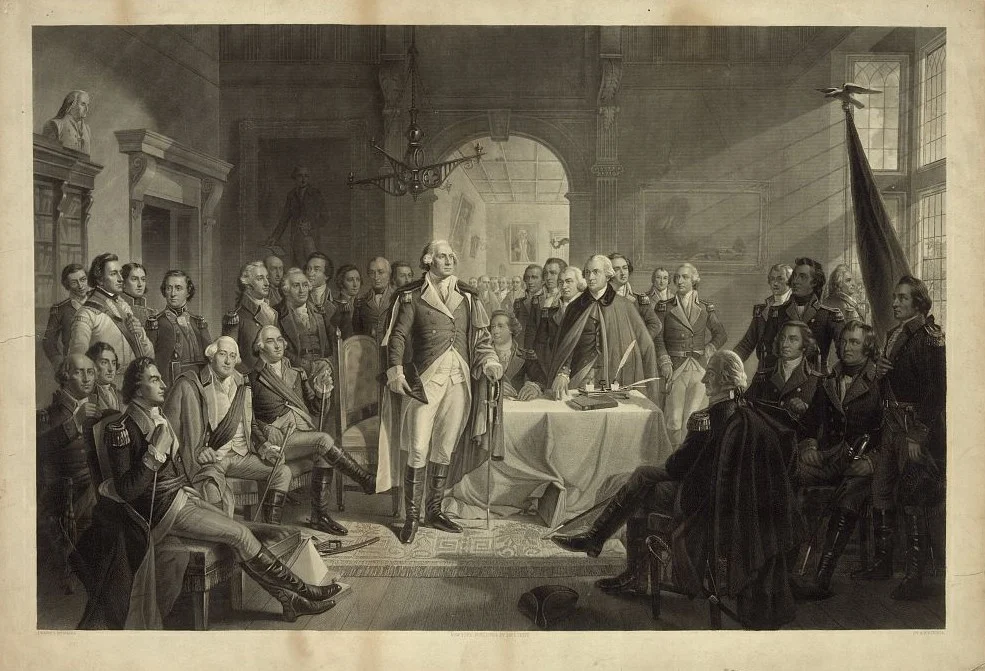

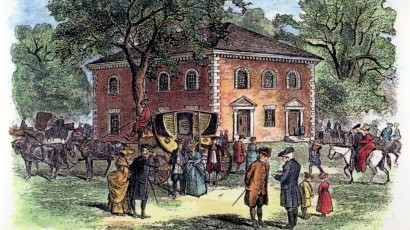

Washington convenes a Council of War. The agenda: selecting officers for the restructured army, based on merit and willingness to continue service. The process is methodical but urgent. Without strong leadership, the army may collapse by winter’s end.

Washington turns to another crisis: firewood and hay. In a letter to James Warren of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, he warns that soldiers are close to violence, fighting over fallen trees to cook their meals. Unless a solution is found, Washington fears the entire force may disperse in the cold.

In today’s General Orders, Washington advises officers who plan to reenlist not to purchase new coats or waistcoats until they are officially assigned to their regiments. Uniforms, he notes, will soon be standardized, and premature spending could lead to unnecessary costs.

Gillam Tailer, a young man recently displaced from Boston, writes Washington a heartfelt letter. “I have left my all,” Tailer writes, explaining that the war has upended his merchant training and left him unemployed. He humbly asks Washington for a position, any position, to serve the cause.

Officers have begun recruiting soldiers without proper authorization. Washington orders that all unauthorized enlistments stop immediately and emphasizes that commissions in the new army will be based on merit, not recruitment numbers.

Patriot leader Josiah Quincy Sr. writes Washington with a bold idea: blockade Boston Harbor, trap the British garrison, and starve them into surrender. He supports the plan with detailed topographical analysis of the harbor’s channels.

In a letter to John Hancock, Washington warns that a third to half of his officers, especially captains and below, plan to leave service when their enlistments expire. He expresses “great anxieties” but hopes that increased pay and a sense of patriotism will persuade soldiers to remain.

Governor Jonathan Trumbull of Connecticut writes Washington, requesting an engineer to assess defenses at the vulnerable port of New London. Trumbull, aware of the British naval threat after the burning of Falmouth, seeks to strengthen his colony’s coastline.

Four hundred miles from Washington’s Cambridge headquarters, Lund Washington, the general’s cousin and farm manager, writes a detailed letter from Mount Vernon. Lund is doing all he can to safeguard Washington’s papers, land, and debts while planning how to defend Mount Vernon in case of a British attack. He proposes erecting a battery along the Potomac River to stop enemy ships.

“Mrs. Washington...has often declared she woud go to the Camp if you woud permit her…”, he writes.

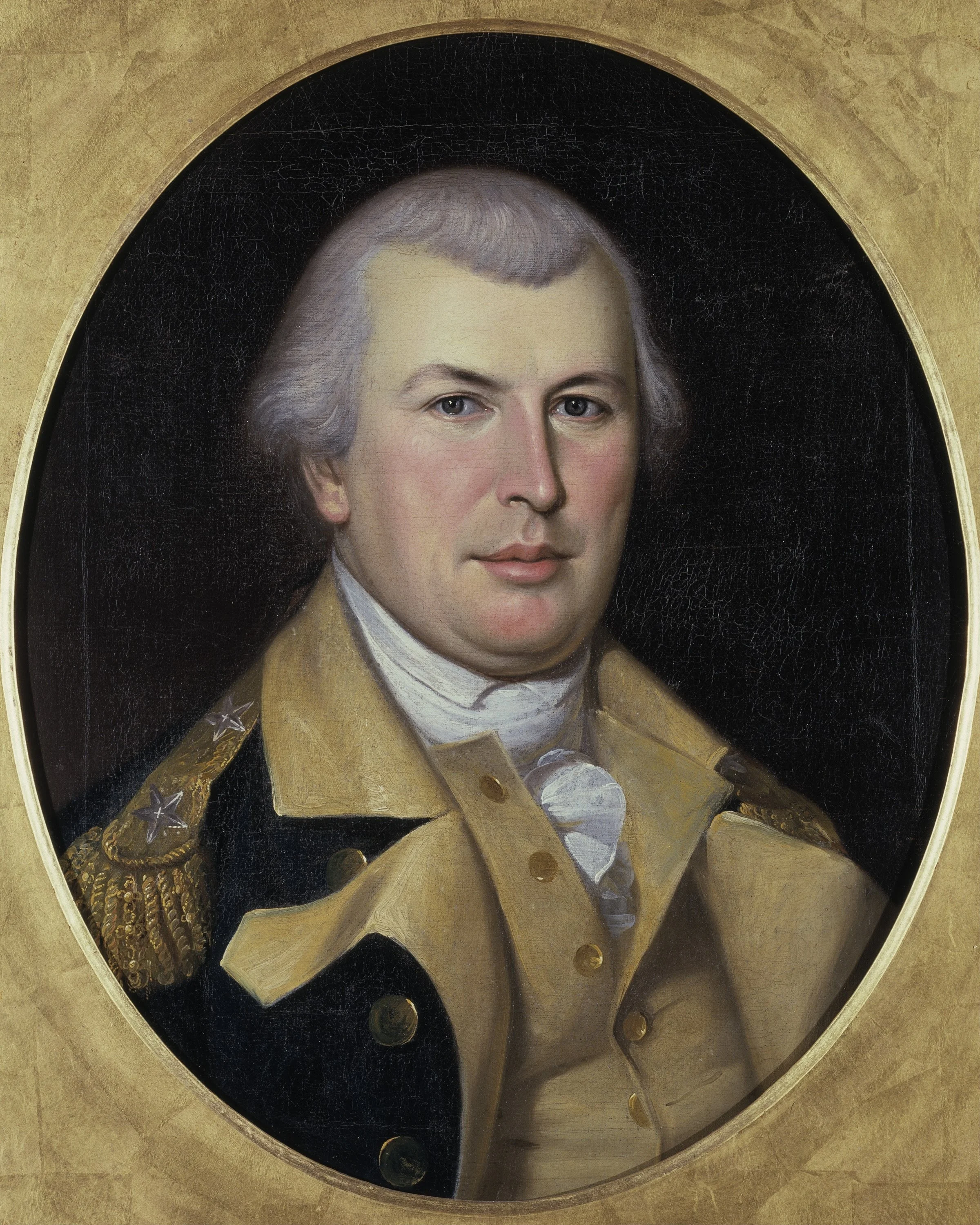

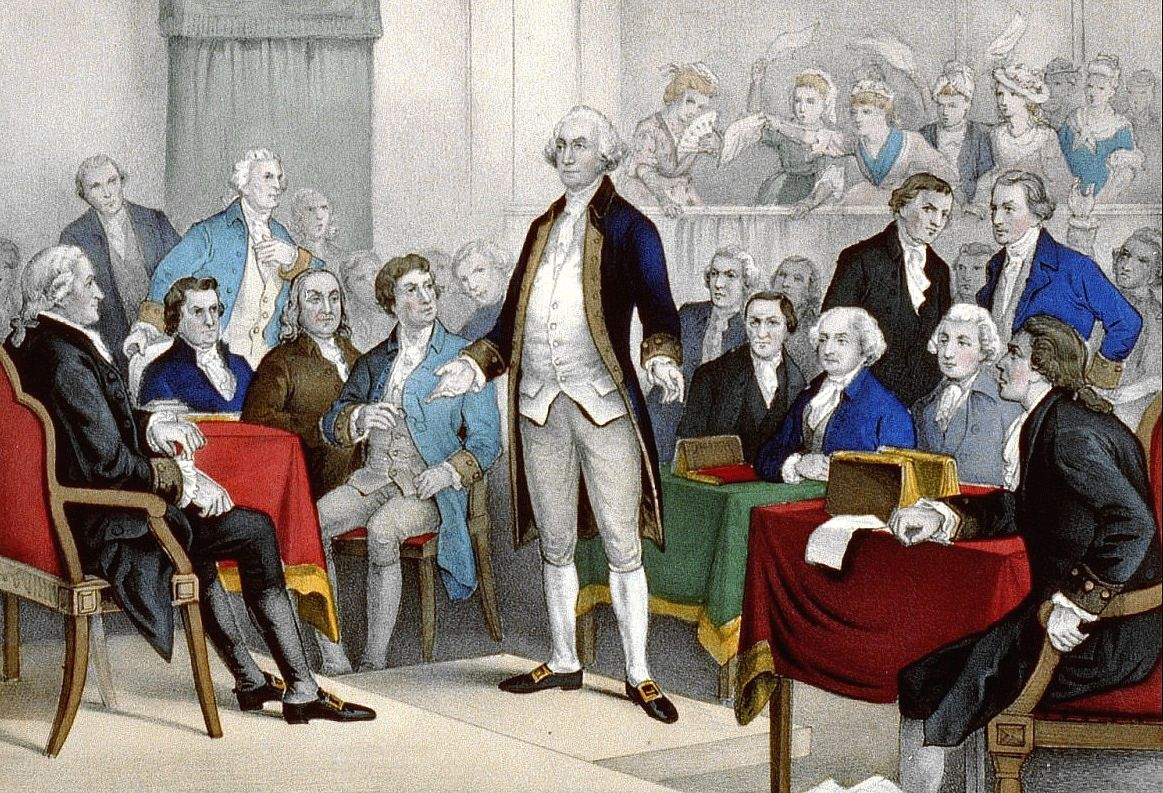

General Washington has astonished his most intimate friends with a display of the most wonderful talents for the government of an army. His zeal, his disinterestedness, his activity, his politeness, and his manly behavior to General Gage in their late correspondence have captivated the hearts of the public and his friends. He seems to be one of those illustrious heroes whom providence raises up once in three or four hundred years to save a nation from ruin. If you do not know his person, perhaps you will be pleased to hear that he has so much martial dignity in his deportment that you would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand people. There is not a king in Europe that would not look like a valet de chamber by his side…

- Dr. Benjamin Rush to Dr. Thomas Ruston

With winter approaching, Washington urges officers and soldiers to spend their wages wisely—not on coats, but on essentials like shirts, shoes, stockings, and leather breeches. Congress, he explains, will provide uniform coats and waistcoats at cost.

Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island writes Washington, warning that over 300 cattle remain vulnerable on Block Island. Once too lean to slaughter, the animals are now fit for market and exposed to British raiding parties. Cooke proposes killing and salting the beef for Washington’s troops, offering it at a fair price.

In the Canadian wilderness, Benedict Arnold writes Washington. Exhausted, soaked by weeks of rain, and nearly starving, he reports that provisions are dangerously low. Yet Arnold remains hopeful: If the British at Quebec remain unaware of his advance, he may attempt a surprise assault.

Across the Atlantic, King George III addresses both Houses of Parliament. His speech is defiant. The colonies, he says, have thrown off royal authority and now seek to establish “an independent empire.” No longer hoping for reconciliation, the King announces a full military response.

Washington issues urgent orders. The enlistments of many officers are set to expire soon, and uncertainty threatens the stability of the Continental Army. In his General Orders, Washington demands that every officer declare, unconditionally and immediately, whether they will remain in service through December 1776.

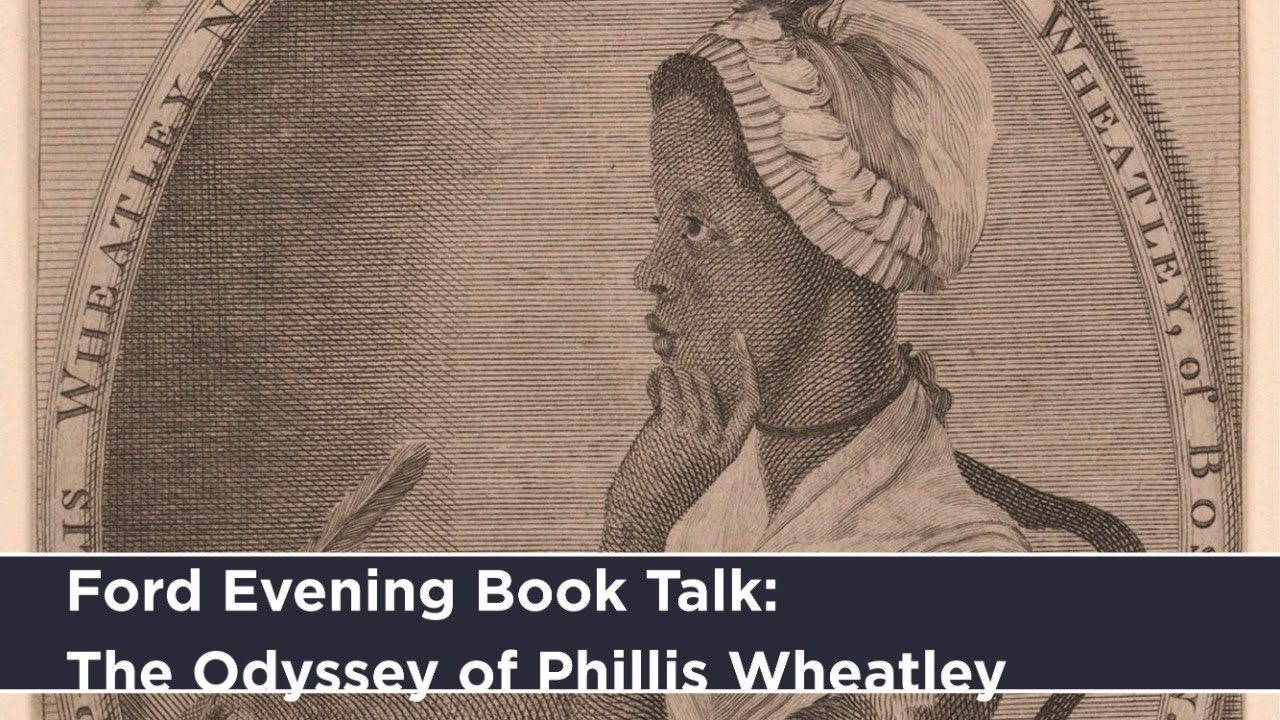

A formerly enslaved poet named Phillis Wheatley writes Washington from Providence, enclosing a moving poem for the commander. She expresses her support for the revolutionary cause, portraying America as “Columbia,” a divine and rising nation.

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side; Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide; A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine; With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.

- Poem by Phillis Wheatley

“For the future Peas and Beans are to be valued by the Commissary General at Six shillings,” Washington writes in the day’s General Orders, reflecting his effort to manage scarce provisions and impose order on military supply chains.

From Nicholas Cooke, governor of Rhode Island, news arrives from Captain Abraham Whipple, just back from Bermuda to retrieve gunpowder. Cooke reports that Bermudians are generally sympathetic to the American cause, but their assistance in providing powder has made them enemies of the British.

News of the British navy’s burning of Falmouth, Maine, finally reaches Washington. To the Falmouth Committee of Safety, he writes that the destruction shows “Contempt of every Principle of Humanity.” Though deeply moved, he must deny their request for troops or supplies—his army is dangerously short on powder, and his authority doesn’t extend far enough to dispatch a detachment.

That same day, he writes John Hancock, President of Congress, describing the attack as an act of “Barbarity & Cruelty” unmatched by civilized nations.

But my Readiness to relieve you … is Circumscribed by my Inability. The immediate necessities of the Army under my Command, require all the Powder & Ball, that can be collected with the utmost Industry, & Trouble. The Authority of my Station does not extend so far, as to impower me, to send a Detachment of Men down to your Assistance—Thus Circumstanced, I can only add my Wishes and Exhortations, that you may repel every future Attempt, to perpretrate the like Savage Cruelties.

- George Washington to the Falmouth Committee of Safety

Washington’s General Orders concern discipline: Colonel David Brewer of the 9th Regiment is dismissed from the Continental Army. Brewer had fraudulently placed his teenage son on the army rolls, though the boy remained at home, and had employed soldiers on his own farm while drawing public supplies.

Richard Henry Lee writes Washington, sharing news of Peyton Randolph’s stroke and subsequent death last night. “Thus has American liberty lost a powerful Advocate, and human nature a sincere friend,” Lee writes.

P.S. Monday morning—’Tis with infinite concern I inform you that our good old Speaker Peyton Randolph Esqr. went yesterday to dine with Mr Harry Hill, was taken during the course of dinner with the dead palsey, and at 9 oClock at night died without a groan—Thus has American liberty lost a powerful Advocate, and human nature a sincere friend.

- Richard Henry Lee to George Washington

The Continental Army headquarters is alive with activity: Delegates from the Continental Congress have arrived to confer with Washington and key political leaders.

Unbeknownst to Washington, Virginia delegate Peyton Randolph suffers a stroke while dining in Philadelphia. Around 9 p.m., Randolph, a stalwart Patriot leader, dies.

Washington issues General Orders directing certain officers to report whether they will re-enlist for another year. Those who decline must give their reasons. With enlistments expiring in December, Washington faces the real threat of a dwindling force.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General William Heath writes to report suspicious activity. A clergyman named Mr. Page, believed to be sympathetic to the Crown, has been seen sketching American fortifications at Roxbury and intends to take the plans to England.

Washington writes to Major Benjamin Tupper, ordering the seizure of two vessels anchored at Martha’s Vineyard. The ships belong to Loyalists who plan to resupply the British troops trapped in Boston. “These are therefore to require you,” Washington writes, “to seize the said Vessels … for the Use of the United Colonies.”

John Hancock writes Washington: A former privateer, Captain John Macpherson, claims to possess a secret weapon capable of destroying every British warship in American waters. Congress has authorized Macpherson to travel to Cambridge.

The Committee of Safety in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, composes a letter to Washington, relaying yesterday’s grim news: Falmouth, Maine (modern-day Portland) has been bombarded and set ablaze by British naval forces. The committee pleads for aid. Portsmouth has only 17 barrels of powder and fears it may be the next target.

Meanwhile, Washington is occupied with a high-level visit: Dr. Benjamin Franklin, in camp as part of a Congressional committee, is consulting with him on military governance and the treatment of prisoners.

Washington gathers his top officers for a Council of War. Congress has urged him to consider an attack on British-occupied Boston before winter sets in. His generals carefully weigh the army’s readiness. One by one, they advise against it. Supplies are low, the harbor is fortified, and the risk is too great.

Meanwhile, British Lieutenant Henry Mowat leads a squadron that bombards and burns the waterfront town of Falmouth, in present-day Portland, Maine. Civilians are given little time to flee. Homes, wharves, and businesses are engulfed in flames.

Winter is coming. Washington orders the quartermaster general to distribute 20 greatcoats to each brigade. These coats are for the sentinels—the men who stand watch through long, cold nights. The coats are to be handed from one guard to the next, a shared defense against the chill.

In Maine, surveyor Samuel Goodwin writes to Washington. Acting on orders given through Colonel Benedict Arnold, he’s provided detailed maps and journals to guide Arnold’s daring expedition through the wilderness to Quebec.

Today, Washington’s mind is on the sea. From his headquarters in Cambridge, he pens urgent instructions to captains Nicholson Broughton and John Selman, ordering them north to the St. Lawrence River. Two British ships are rumored to be sailing to Quebec, laden with 6,000 muskets, powder, and military stores.

Washington sees an opportunity: If intercepted, those weapons could turn the tide of the American invasion of Canada, now underway.

In the day’s orders, Washington instructs that, at sunrise tomorrow, detachments from four brigades are to assemble on Cambridge Common to cut firewood for the army—critical preparation for the harsh New England winter.

Meanwhile, at Mount Vernon, Lund Washington writes with updates from home. He reports that Martha prepares to leave for New Kent County, but she has delayed her trip by a day to pack Washington’s personal papers and valuables, fearing Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, may threaten the estate.

Mrs Washington I believe was under no apprehension of Lord Dunmores doing her an injury until your mentiong it in several of your last Letters she intended to set off tomorrow down the Country I propose to her to put whatever she thought Most Valuable into trunks...

- Lund Washington to George Washington

Brigadier General John Sullivan reports from Winter Hill with a list of 60 soldiers deemed unfit for duty: men who are sick, debilitated, and unlikely to recover before the end of the campaign. Sullivan urges their immediate discharge to ease the strain on resources.

George Mason, writing from Gunston Hall, updates Washington on the recent activities of the Virginia Convention. Mason praises the passage of laws for a manufactory of arms, gunpowder production, and a standing Committee of Safety—all crucial to Virginia’s defense.

Washington writes to his brother, John Augustine Washington. He mentions that Martha may join him at camp, though he worries the season is too far gone.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, the Continental Congress takes a historic step: It resolves to fit out two swift-sailing vessels to intercept British supply ships, essentially authorizing the creation of a Continental Navy.

Washington writes to John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, contemplating how to maintain the army through the winter. He is considering ways to reward regiments that have performed well, perhaps with extra supplies. It’s a rare incentive in a time of scarcity.

Meanwhile, letters from desperate civilians reach his desk — four women from Maine plead for help after their husbands were captured by the British.

From Portsmouth, the New Hampshire Committee of Safety writes Washington concerning the capture of the Prince George, a British ship loaded with flour. The colony’s own troops are starving, and they ask for Washington’s permission to keep part of the cargo and sell some to local residents, holding the profits until Congress decides its fate.

Reverend Samuel West of Plymouth also writes Washington. While serving as a volunteer chaplain, his horse was mistakenly taken and sold by an officer. Though given a new horse to ride home, West is unsure if it was a loan or a gift.

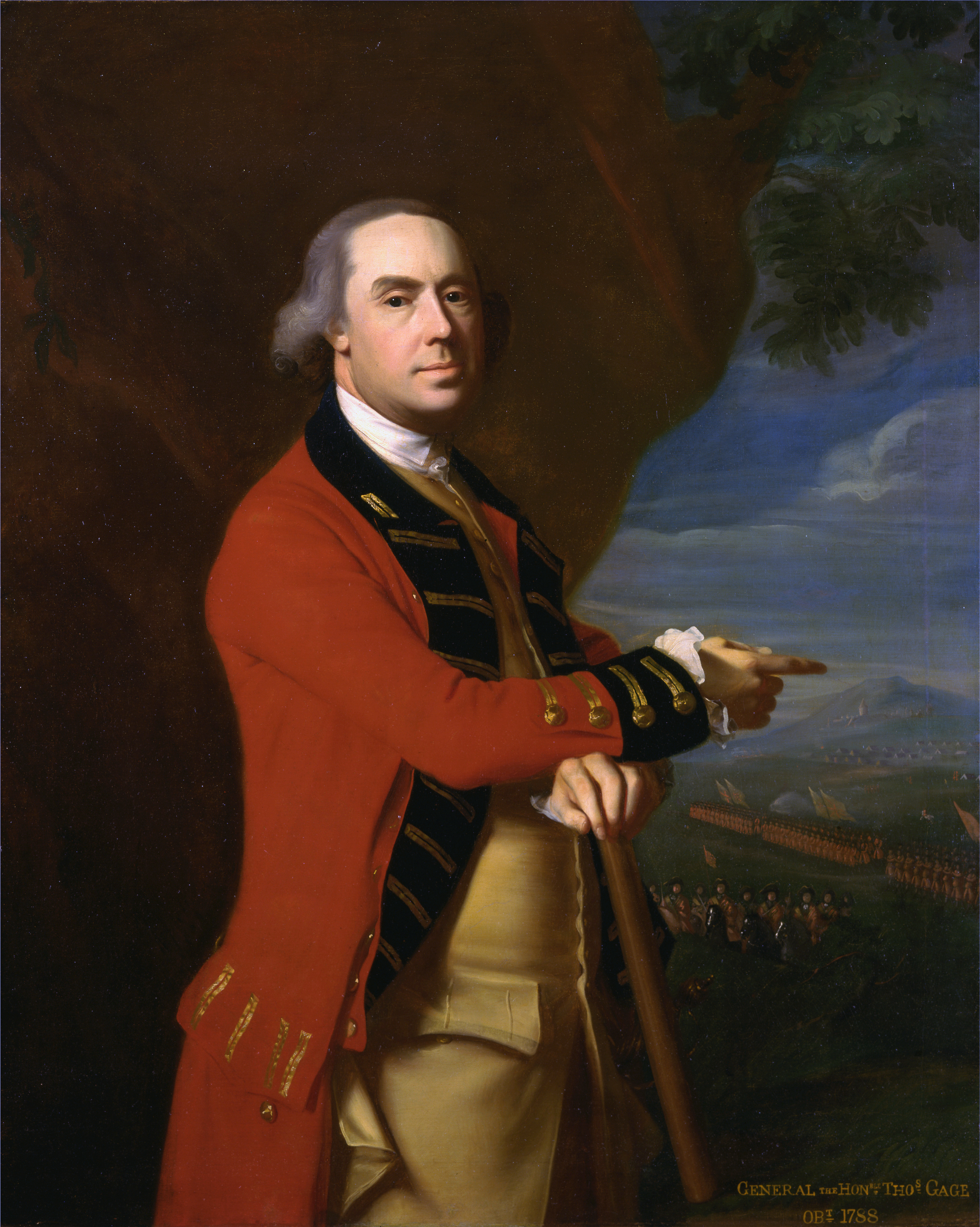

Across the lines in Boston, a major shift occurs today. General Thomas Gage, the British commander-in-chief in North America, leaves Boston permanently.

He boards a ship bound for England, relieved of command after the costly failure at Bunker Hill and criticism of his handling of the American rebellion. His replacement, General Sir William Howe, assumes command.

Major Christopher French, a captured British officer held in Hartford, pens a sharp response to Washington. French challenges Washington’s restriction on British prisoners wearing their swords. Denying them that right, he insists, is not a matter of “mere punctilio” but one of honor.

“I gloried in serving my King & Country and should always do so, and I glory even in repeating it to you…” French writes.

Washington convenes a Council of War. The agenda: how to structure the Continental Army for the winter. The council unanimously agrees that 20,372 men, formed into 26 regiments, will be needed for a winter campaign capable of both defending and potentially striking against the British in Boston.

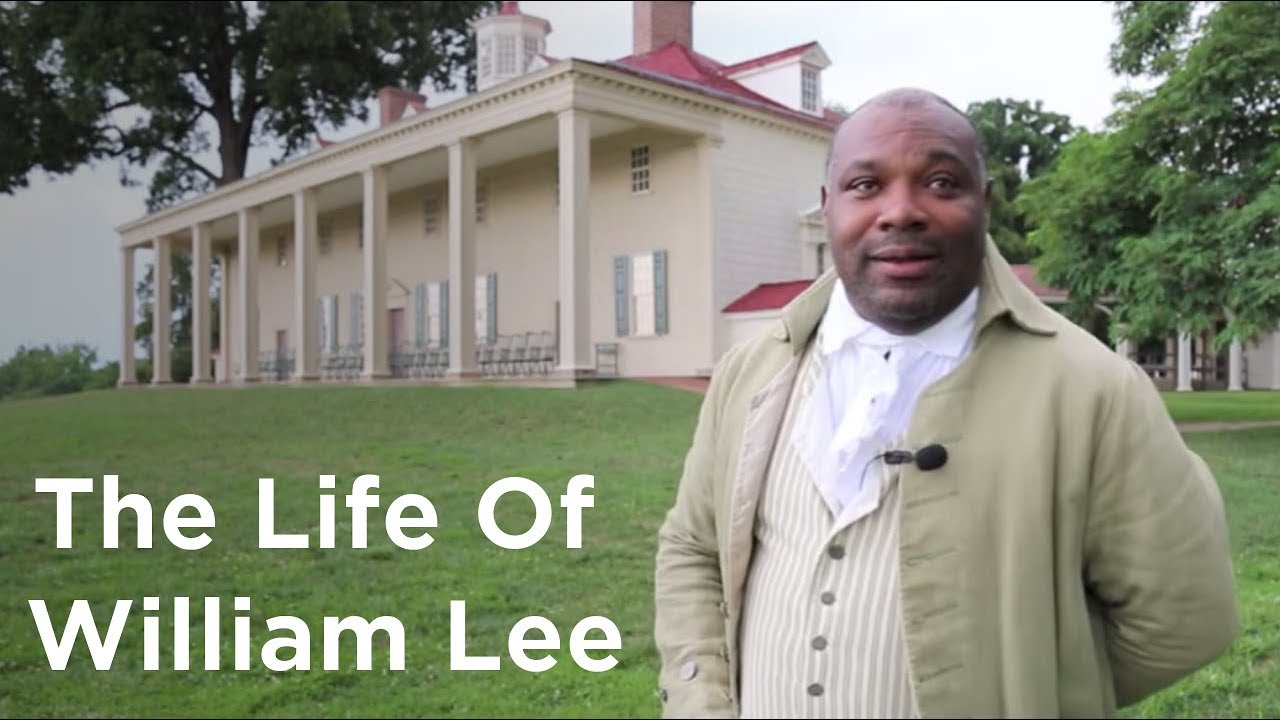

The meeting’s final topic, whether to reenlist Black soldiers, especially enslaved men, leads to a clear consensus: Enslaved people are excluded, and most officers oppose reenlisting any Black men at all.

Washington issues the day’s General Orders from his Cambridge headquarters. He reports that a court-martial has found Lieutenant Colonel Abijah Brown guilty, not of fraud, but of using two enlisted men to work on his farm.

Brown is fined four pounds, and Washington warns that ignorance will no longer excuse such behavior. The fine is to be paid to the hospital for the care of sick soldiers.

Faced with the onset of a New England winter, Washington writes to the Massachusetts General Court to voice concern over the army’s dwindling firewood supplies. Woodcutters are reluctant to sell, and prices are rising.

He also urges the Court to consider using abandoned or vacated houses in Cambridge as makeshift barracks.

Washington drafts a lengthy, grave letter to John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. He reveals that Dr. Benjamin Church, the director general of the Continental Army’s medical services, has been caught spying for the British.

Church has been arrested, and Washington is requesting Congress’s guidance on how to proceed, hinting that the Articles of War may need amending to deal with this type of treason.

I have now a painful tho a necessary Duty to perform respecting Doctor Church Director General of the Hospital.

- George Washington to John Hancock

Washington issues detailed instructions to Colonel John Glover and Stephen Moylan to equip two armed vessels to patrol the New England coast and target British supply vessels.

Dr. Benjamin Church—a prominent patriot turned British spy—is questioned at a Council of War, which unanimously deems his actions criminal. Washington orders Church held in close confinement and refers the case to the Continental Congress.

Washington issues a firm General Order banning all gambling, specifically naming games like “toss-up” and “pitch and hustle.” Washington isn’t opposed to recreation, but he draws a hard line against vice that undermines discipline.

He turns his attention to a far more serious breach. Dr. Benjamin Church, recently arrested under suspicion of treason, writes to Washington to plead for mercy. The letter is riddled with defensive justifications, admissions of falsehoods, and professions of patriotism. But Washington remains skeptical.

I have much of folly, precipitation and Indiscretion to be forgiven I candidly confess, that forgiveness I most humbly intreat… I suffer inexpressibly from my own reflections, I condemn my heedless Folly most sincerely.

- Benjamin Church to George Washington

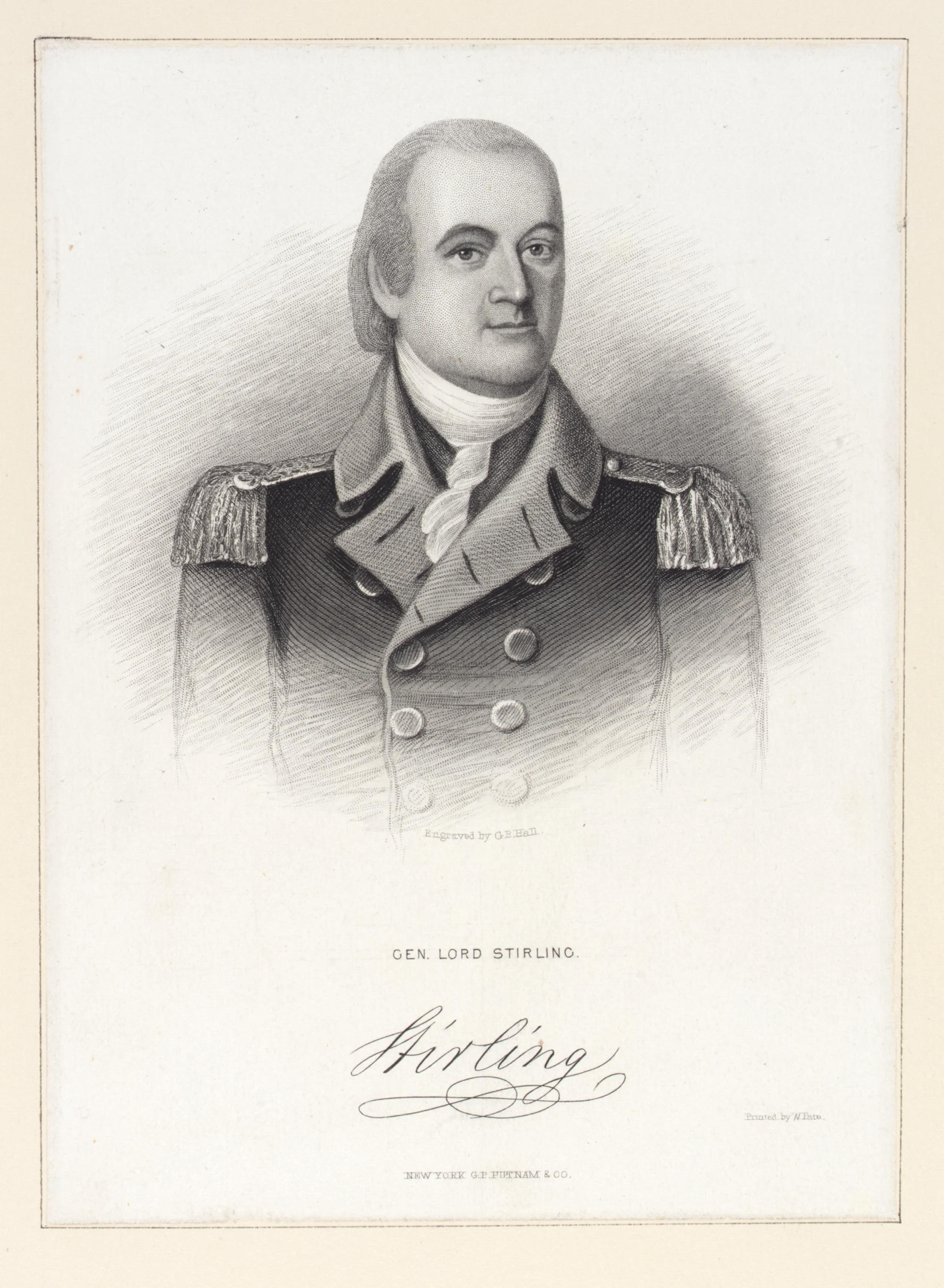

In New Jersey, William Alexander, known as Lord Stirling, writes to Washington, reporting he is under political fire from the royal governor for assuming a military role while still technically a crown-appointed counselor. He promises to send copies of their heated correspondence for Washington’s "amusement."

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the town’s Committee of Safety reports they have just seized the Prince George, a British supply ship carrying nearly 1,900 barrels of flour meant for General Thomas Gage’s army in Boston.

In today’s orders, Washington instructs regimental carpenters to begin building winter barracks, clear recognition that the siege of Boston will not end soon.

Washington writes another letter to his brother Samuel, who is considering the purchase of a mill in Virginia. Washington warns him sharply about the risks: the mill is costly, the dam has failed before, and in these uncertain times, finding skilled labor and markets is doubtful.

In his General Orders, Washington postpones a court of inquiry scheduled for today “on account of the Indisposition of Dr Church.” What Washington does not publicly state is that Dr. Benjamin Church, director general of the hospital, was arrested yesterday on charges of espionage.

In a letter to his brother Samuel, Washington shares military updates and laments the loss of personal letters home. “Such is the infernal curiosity of some of the Scoundrel Postmasters…”

The goodness of the cause bids me hope for protection, & I have a perfect reliance upon that Providence which heretofore has befriended & Smiled upon me.

- George Washington to Samuel Washington

Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island reports to Washington that British transports and warships are spotted in Vineyard Sound, likely hunting livestock.

Lund Washington, the general’s cousin and farm manager, pens a letter to report domestic news from Mount Vernon: the storehouse and wash house are under construction, but progress is slowed by fever and ague—malaria—that plagues both enslaved workers and hired craftsmen.

From his headquarters, Washington drafts a letter to the Massachusetts General Court introducing them to “an Oneida Chief of considerable Rank in his own Country.”

The chief, curious about the Continental Army, represents a tribe sympathetic to the American cause. Washington urges the court to extend proper civilities, understanding the political importance of Native alliances. “I have studiously endeavoured to make his Visit agreeable.”

Benedict Arnold writes Washington concerning James McCormick, a soldier under his command convicted of murder. Arnold is forwarding the man to Washington for judgment and potential mercy. Arnold describes the condemned as “simple and ignorant,” with a reputation for being peaceable.

Far to the north, General Richard Montgomery, having led his army from Fort Ticonderoga, lays siege to Fort St. Jean in British Canada. The fort is a strategic gateway on the Richelieu River, guarding the approach to Montreal.

Washington responds to Major Christopher French, a captured British officer being held in Hartford. French has written complaining about his treatment—specifically, being denied the right to wear his sword, a point of military honor. Washington’s tone is measured but unmistakably firm.

“When I compare the Treatment you have received with that which has been Shewn to those brave American Officers... I cannot help expressing Some Surprize that you Should thus earnestly contest Points of mere Punctilio.”

From his Cambridge headquarters, Washington issues detailed orders to regulate furloughs, streamlining a system that has burdened his top officers. No more than two privates or one non-commissioned officer per company may be absent at once, and officers must go through a formal chain of command to receive leave.

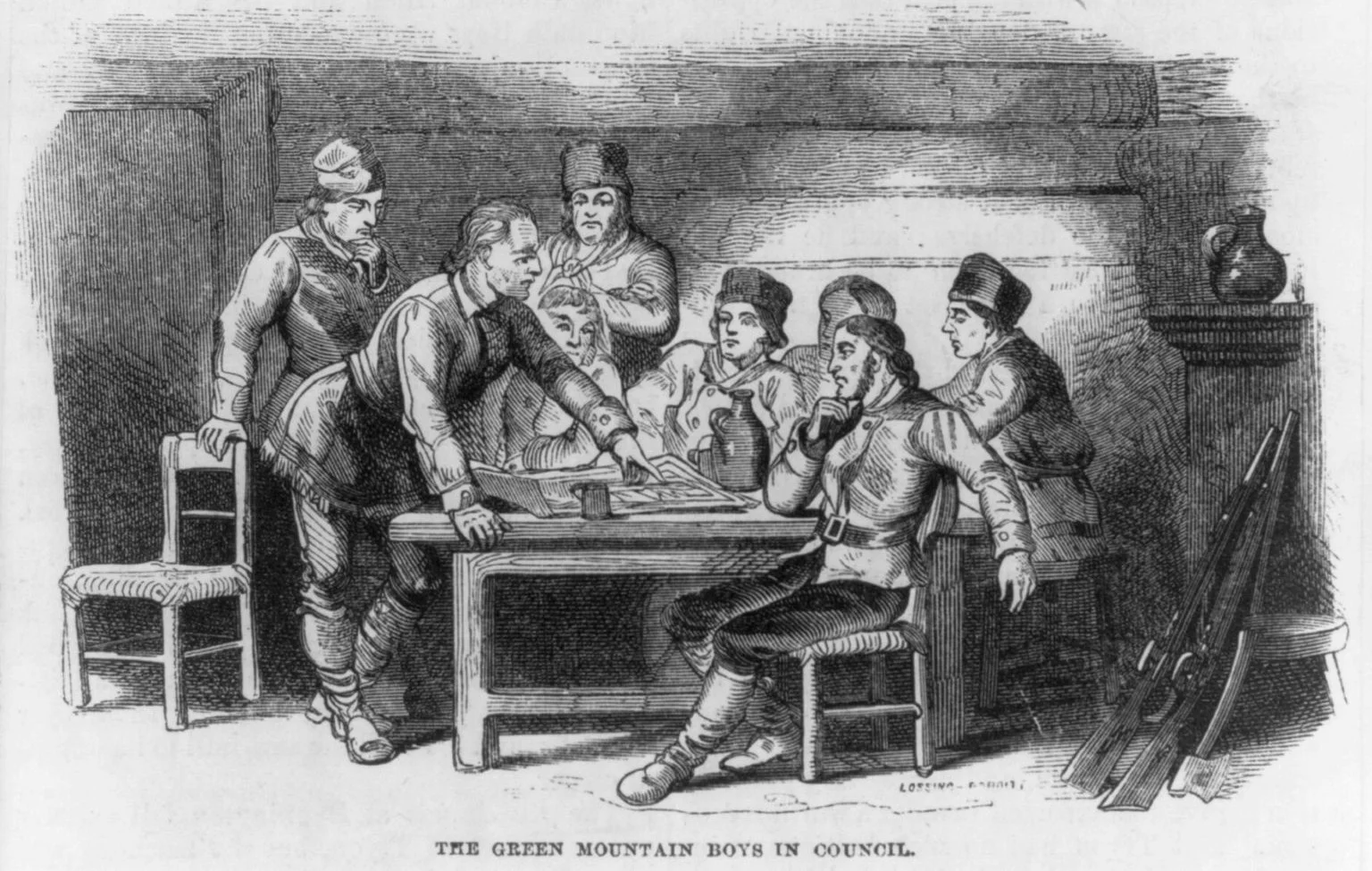

In Canada, Ethan Allen, the brash co-leader of the Green Mountain Boys, is captured by the British during a failed attempt to take Montreal. His capture is a major blow to American morale.

In his General Orders, Washington reviews more court-martial decisions. He also includes a resolution from the Massachusetts House of Representatives, requesting detailed returns for each regiment raised by Massachusetts: names of enlisted men, those who have died, and those drafted for the expedition to Quebec.

The request is meant to help properly account for blankets and supplies issued under enlistment terms.

Washington oversees the continued siege of British-held Boston.

In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress meets to strengthen support for Washington’s army. They appoint a committee—including Francis Lewis and Silas Deane—to purchase £5,000 worth of woolen goods to be sold directly to soldiers at cost, a crucial step with winter approaching.

Washington spends the day enforcing discipline after a mutiny aboard the schooner Hannah, the Continental Army’s first naval vessel. Its crew, made up of soldiers, had recaptured the Unity, an American merchant ship taken earlier by the British, and expected to claim it as a prize. When Washington ordered the ship returned to its original owner, the crew rebelled.

In today’s General Orders, he confirms harsh punishments: 13 men are sentenced to lashes and dismissal, and 21 are fined.

Unaware of Hancock's letter of financial support two days prior, Washington pens a long and detailed letter to the president of the Continental Congress. Supplies are low. The army is ill-clothed. Pay is behind. Re-enlistment is uncertain. Washington knows that if these issues are not addressed, the army may dissolve by winter.

"It gives me great Pain, to be obliged to sollicit the Attention of the Honorable Congress, to the State of this Army, in Terms which imply the slightest Apprehension of being neglected..."

Washington issues General Orders requiring all officers to appear in person to receive their Continental commissions, declaring that “no person is to presume to demand a Continental commission” unless they can produce a valid one from their colony of origin.

General Philip Schuyler writes from Ticonderoga, gravely ill with a "bilious fever." He reports that he and General Richard Montgomery had attempted an assault on Fort St. Jean, but the effort faltered under the weight of swampy terrain, enemy fire, and low morale.

Washington issues a special order authorizing Clark & Nightingale, merchants from Providence, to outfit the sloops Fly and Neptune to acquire ammunition from the West Indies. Washington is authorizing covert trade in defiance of British restrictions.

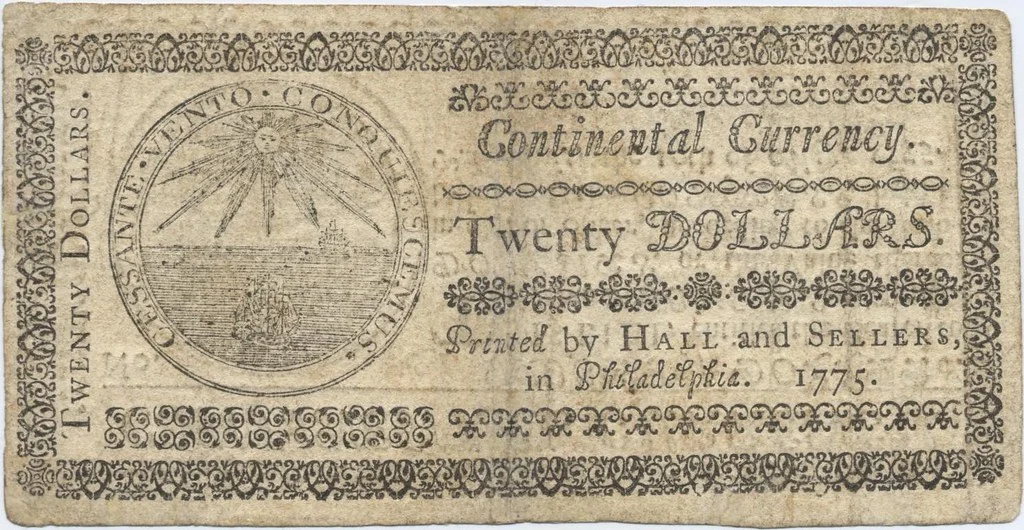

John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, writes Washington with enormous news: Over half a million dollars in Continental currency has been dispatched for the maintenance of the army. This transfer of funds is one of the earliest large-scale distributions of the new national currency.

Washington reacts to news that American agents may have already raided the powder magazine at Bermuda. He had considered sending Captain Abraham Whipple to seize it, but, given the news in Philadelphia papers, he now believes the risk and expense may no longer be justified.

Instead, Washington turns his attention to another proposal—importing gunpowder from Bayonne, France. Though he likes the idea, he is wary about the extent of his authority.

I must add that I am in some Doubt as to the Extent of my Powers to appropriate the publick Money here to this Purpose.

- George Washington to Nicholas Cooke

The siege of Boston continues with both armies entrenched and within sight—American lines are just 600 yards from the British. Washington notes that “the Enemy and we are very near Neighbours.”

In the same letter, to Thomas Everard, Washington requests legal help to retain his western land holdings. His efforts to develop these lands near the Ohio and Kanawha rivers have failed twice—laborers deserted, provisions were scarce, and hostile territory blocked progress. He fears losing the land under Virginia law unless a petition is filed in time.

Washington reviews and approves two court-martial sentences. One concerns Sergeant James Finley, of Captain Price’s rifle company, who was convicted for “expressing himself disrespectfully of the Continental Association, and drinking Genl Gage’s health,” a blatant sign of Loyalist sentiment in a time of war.

The court orders Finley to be publicly humiliated. He will be stripped of his arms and accoutrements, put in a horse cart with a rope around his neck, and drummed out of the army, permanently barred from future service.

Rhode Island’s deputy governor Nicholas Cooke urgently writes to Washington. A report has surfaced, published yesterday in the Cambridge Chronicle, claiming that over 100 barrels of gunpowder have been stolen from a British magazine in Bermuda, possibly by American ships.

Cooke, fearing the mission to seize powder might now be redundant, asks Washington whether he should recall Captain Abraham Whipple, who has been sent to Bermuda to secure more powder for the American cause.

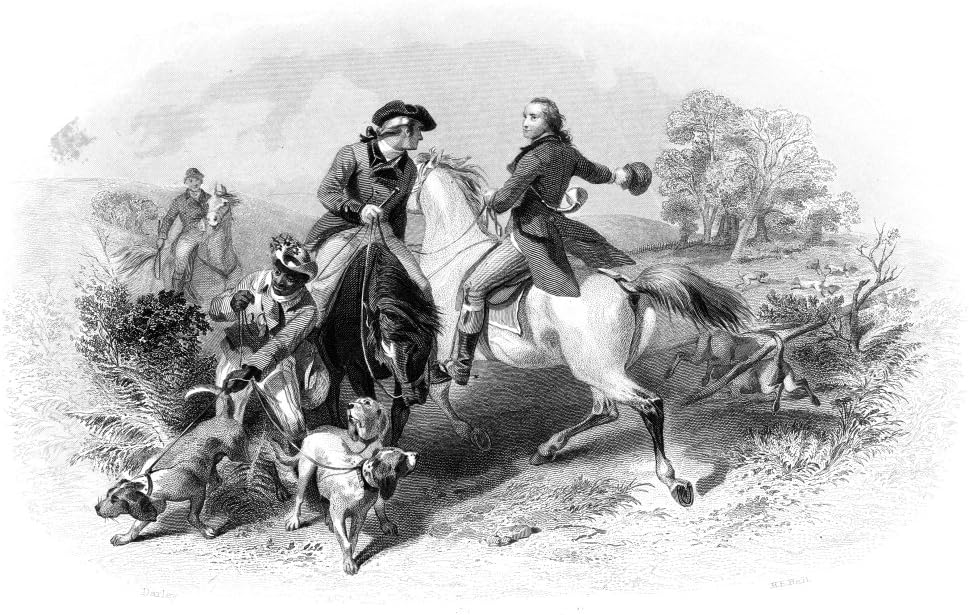

Washington issues two letters to Colonel Benedict Arnold, who leads a bold expedition through the Maine wilderness toward Quebec. In his personal letter, Washington reminds Arnold that he marches not through enemy territory, but among “Friends and Brethren,” and urges his men to show discipline and respect for civilians.

Washington also provides a formal set of 14 detailed orders. These guide Arnold’s movements, his coordination with General Philip Schuyler, and his conduct toward Canadian civilians and Indigenous nations.

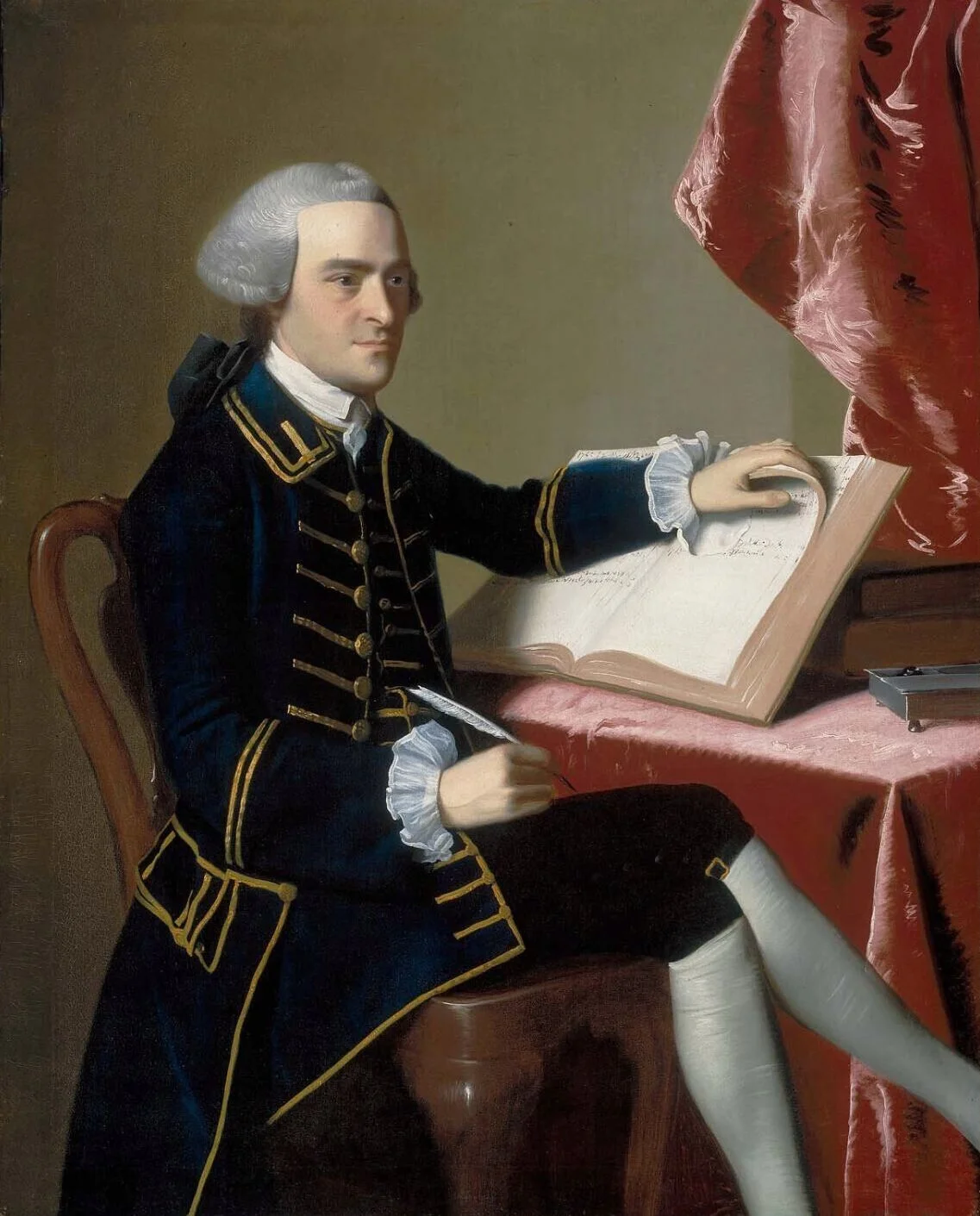

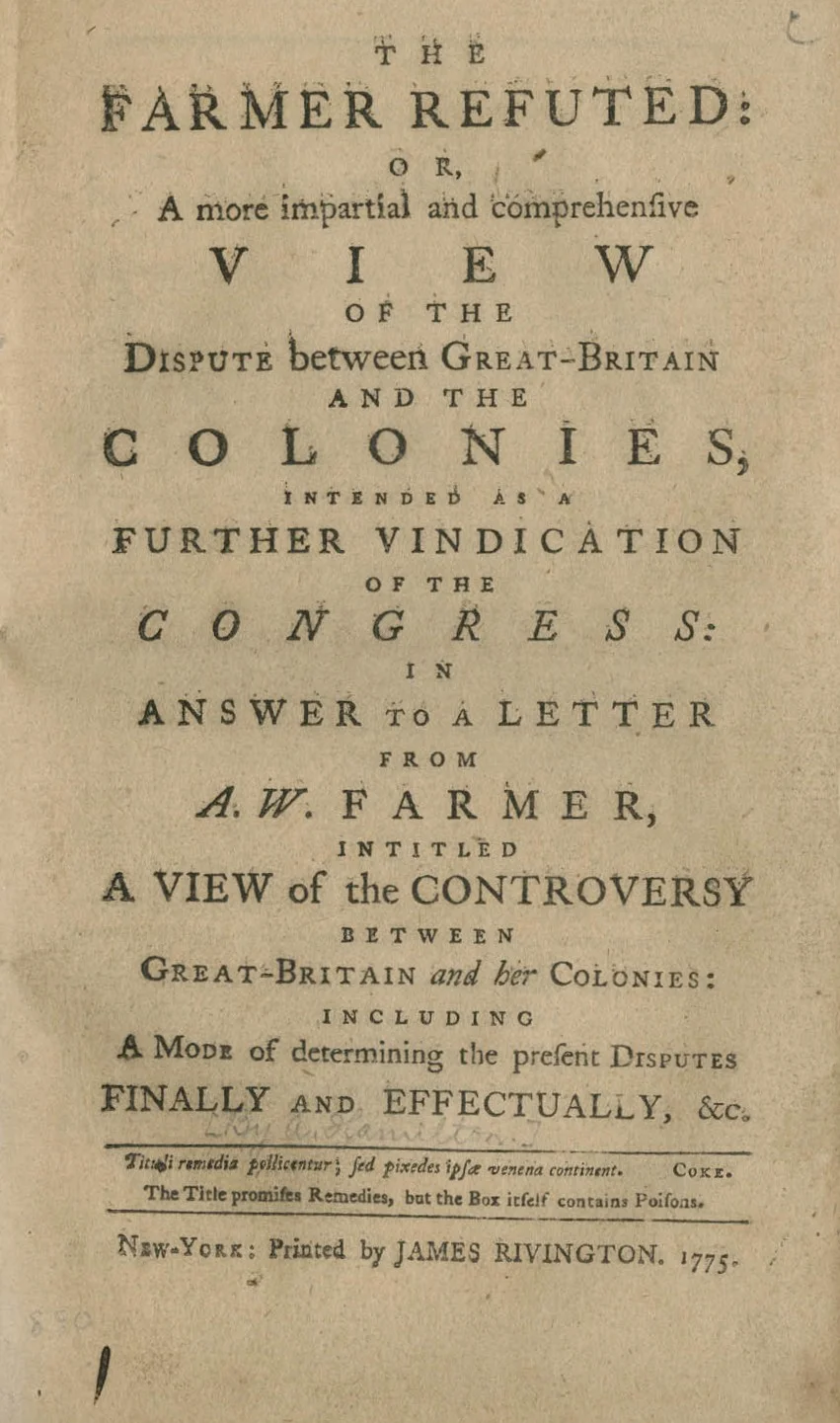

George Washington and Benedict Arnold

You are intrusted with a Command of the utmost Consequence to the Interest & Liberties of America: Upon your Conduct & Courage … the Safety and Welfare of the whole Continent may depend.

- George Washington to Benedict Arnold

The actions of September 10 bring consequences: Thirty-three riflemen from Colonel William Thompson’s battalion, Pennsylvania men known for their skill and fierce independence, were tried by court-martial yesterday and found guilty of “disobedient and mutinous behaviour.” Washington orders each man to pay a fine of 20 shillings, to be deducted from next month’s pay.

Though their punishment may seem mild for mutiny, Washington likely recognizes that these are raw troops, many far from home, and this is their first offense.

At 4 p.m., Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin, stationed in Chelsea, Massachusetts, sends Washington a short but focused dispatch.

He reports unusual activity at Charlestown Ferry: heavily loaded British boats moving from Boston to Charlestown last night and this morning. The boats returning from Charlestown are empty, hinting at troop movements or supply logistics.

Washington convenes a Council of War with his top officers, including Generals Ward, Lee, Putnam, Greene, Sullivan, and others. He presents a bold proposal: a coordinated amphibious assault on British-held Boston, supported by an attack on the Roxbury lines.

Washington warns that without decisive action, the army may not survive the coming months. Yet the generals unanimously reject the plan. The risks of failure are too great.

Word arrives that Pennsylvania riflemen threaten to mutiny. Angered by the imprisonment of a comrade for insubordination, they seize their weapons and march toward the main guardhouse in defiance, vowing to release him or die trying.

Washington responds without hesitation. He orders 500 troops with fixed bayonets to intercept them and personally rides out with Generals Charles Lee and Nathanael Greene. The show of force works; the mutineers, realizing the gravity of their actions, surrender without resistance and are disarmed on the spot.

Washington issues a General Order: All colonels and field officers must sleep in the encampments of their regiments. Officers have been shirking this responsibility, and Washington is no longer willing to tolerate it.

“The Major General commanding the division of the army ... is to be very exact in obliging the Colonels and Field Officers, to lay in the Encampments of their respective regiments; and particularly, the Colonel and Lieutenant Colonel of the 30th Regiment.”

Washington drafts a circular letter to his generals, summoning them to a Council of War.

He proposes a bold idea: a surprise attack on British forces in Boston before winter sets in. He details his concerns—scarcity of powder, lack of clothing and blankets, short enlistments—and worries the army may disband before spring.

Washington issues General Orders noting he has received “repeated complaints” from regimental surgeons who say they’re not getting the medical supplies needed for sick soldiers. At the same time, the director general of the hospital, Dr. Benjamin Church, insists that regimental hospitals are expensive and inefficient—an unacceptable burden on the Continental finances.

Washington, concerned both for the sick and the public trust, orders an official Court of Inquiry to investigate.

Washington begins the day by cracking down on disorder in camp. In a stern General Order, he bans unauthorized sutlers from selling liquor to the troops, blaming drunkenness for poor discipline and lax duties.

Washington then turns to diplomacy and strategy. He finalizes his “Address to the Inhabitants of Canada,” appealing to shared ideals of liberty and urging Canadians to support the American cause. Benedict Arnold will carry the address on his march through the Maine wilderness to take Quebec.

At Washington’s order, a special detachment of 676 handpicked volunteers—woodsmen and riflemen from Virginia and Pennsylvania—will parade tomorrow morning in Cambridge under Colonel Benedict Arnold. These men are bound for a grueling march through Maine to attack British-held Quebec.

Beyond Cambridge, Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull reports that British warships are harassing towns along Long Island Sound. He’s deployed local militia to defend the coastline.

From his Cambridge headquarters, Washington writes to General John Sullivan about a New Hampshire officer, Lieutenant Sanborn, who was confined for misconduct. Washington agrees to dismiss Sanborn without trial, if he is properly reprimanded.

Next, Washington addresses the Massachusetts Council regarding a colonel who lacks a formal commission. Though the legislature has not acted, Washington waives formalities, agreeing to issue a Continental commission if the Council confirms the man’s legitimacy—prioritizing function over red tape.

Washington turns his attention to preparations for a bold maneuver far to the north: the invasion of Canada. He writes detailed instructions to Reuben Colburn, a Maine boatbuilder and patriot.

Colburn is ordered to begin construction of 200 "batteau"—light riverboats crucial to a secret expedition being planned under Benedict Arnold. These vessels must be capable of carrying seven men and provisions through the wilderness on a route few soldiers have ever attempted.

Washington formalizes the commission of Captain Nicholson Broughton, giving him command of the schooner Hannah—the first of several vessels he will send out to harass British supply ships. In his detailed instructions, Washington emphasizes strategy over glory: “You are particularly charged to avoid any Engagement with any armed Vessel ... the Design of this Enterprize being to intercept the Supplies of the Enemy.”

Washington is laying the foundations of what will become the Continental Navy.

A troubling report reaches Washington: The body of a soldier in Colonel Woodbridge’s regiment has been “taken from his grave.” Outraged, Washington issues orders demanding the culprits be found and punished.

From nearby Chelsea, Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin writes urgently, reporting that the town’s residents, already impoverished and short on space, cannot adequately house the troops stationed there through the coming winter. He requests Washington’s permission to build barracks for 70 to 80 soldiers.

Complaint has been made to the General, that the body of a Soldier of Col. Woodbridge’s Regiment, has been taken from his grave by persons unknown; The General and the Friends of the deceased, are desirous of all the Information that can be given, of the perpetrators of this abominable Crime, that he, or they, may be made an example, to deter others from committing so wicked and shameful an offence.

- Washington's General Orders

Washington issues urgent orders: Massachusetts regimental commanders must submit detailed abstracts of pay due to their soldiers for August. He wants them paid immediately, an effort to maintain morale amid complaints and confusion over whether soldiers should be paid by calendar or lunar months.

Washington is also chasing weapons and powder. Having heard that the Providence firm of Clark & Nightingale has imported gunpowder, lead, and 500 arms, he dispatches his aide-de-camp, Captain George Baylor, to negotiate a purchase.

At his Cambridge headquarters, Washington begins the day with pressing orders. Over 600 soldiers are to march to Plough'd Hill, a newly occupied strategic point near British-held Boston. Surgeons are assigned to accompany them. Preparation for conflict feels imminent.

In a letter to New York’s Peter Van Brugh Livingston, Washington thanks him for a vital shipment of powder and rifles but urgently asks for more. The army’s position on Plowed Hill is strong, but without ammunition, it cannot be held.

Logistical troubles continue. Bread remains poor in quality, prompting complaints from the ranks. Washington reminds his quartermaster general and commissary general to enforce earlier directives about food standards.

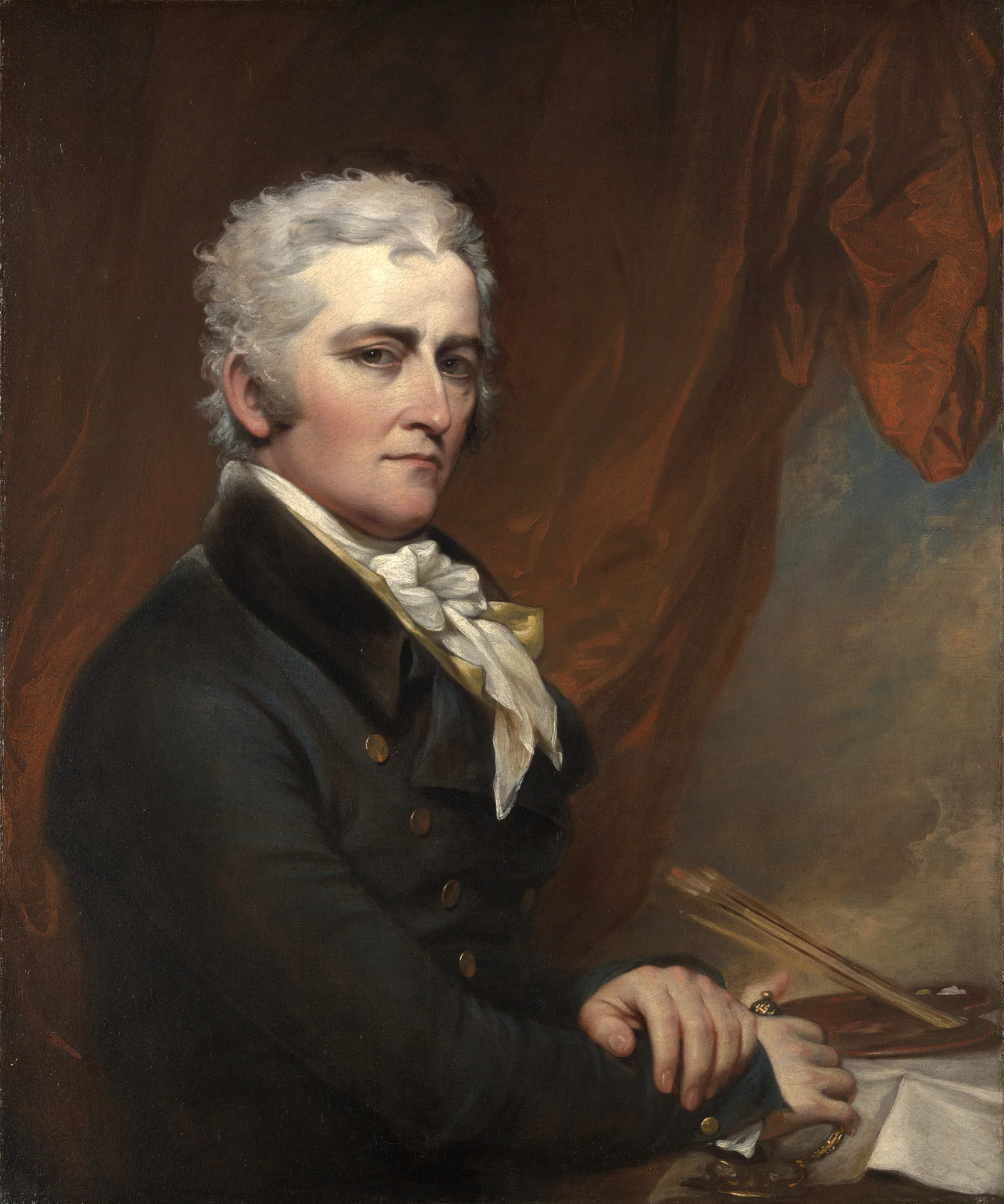

In a letter to the Massachusetts Council, he accuses local merchants of hoarding firewood, hay, and oats to raise prices. He urges price controls or, if necessary, forced requisition.

…I am well acquainted with Genl. Washington who is a Man of very few words but when he speaks it is to the purpose, what I have often admired in him is he allways avoided saying any thing of the actions in which he was Engaged in [the] last War, he is uncommonly Modest, very Industrous and prudent…

- Charles Willson Peale to Edmund Jennings

Washington issues General Orders addressing a growing health crisis in the camp. Dysentery, referred to then as "bloody-flux,” is ravaging the ranks. The suspected culprit? New cider (unfermented, likely full of microbes from unclean fermentation).

Quartermasters are directed to publish notices warning local residents: Anyone caught bringing new cider into the camps after August 31 will have their barrels smashed on the spot.

At six o’clock this morning, Major General Philip Schuyler picks up his pen in Albany. He’s just returned from a critical Indian treaty council with representatives of the Six Nations (Iroquois Confederacy).

The meeting has yielded important, if cautious, results: the Six Nations, wary of being drawn into what they call a “family quarrel,” declare they will remain neutral—for now. Schuyler is relieved that the Native confederacy has not aligned with the British, but he knows this neutrality is fragile.

Washington issues the day’s General Orders. As always, it includes the “Parole”—a daily password used by officers and sentries to verify identities and maintain security. Today’s Parole is Amboy, and the countersign is Brookline—a reflection of the sprawling network of guards encircling British-occupied Boston.

These codes are updated each day to prevent infiltration by enemy spies or loyalists.

Reports pour into headquarters: Captain Richard Dodge informs Washington that two men — one who fled British-occupied Boston, another who escaped the warship Glasgow — hope to enlist. General Artemas Ward warns that the British are preparing to fortify Dorchester Hill.

In Canada, General Richard Montgomery departs Fort Ticonderoga, leading a force toward Fort St. Jean in Quebec. This marks the beginning of the invasion of Canada, a bold American effort to draw French-speaking Canadians into the rebellion and secure northern borders.

Washington remains focused on order and discipline. He confirms the court martial of Lieutenant William Ryan for disobeying superior officers—ordering him cashiered (dismissed in disgrace) immediately.

He turns next to the army’s logistics: ensuring every brigade has armorers to repair weapons, and directing Captain Francis to begin immediate brick production with skilled men from several regiments.

On this day, Washington responds to British General William Howe, firmly denying accusations of misconduct by American troops: “I flatter myself you have been m[is]inform’d as to the Conduct of the Men under my Command complained of in yours of yesterday.”

In London, a critical shift in British policy is formalized. Today, King George III signs a proclamation declaring that the American colonies are in “a state of open and avowed rebellion.” The conflict is now an official war from the British perspective.

Whereas many of our subjects…forgetting the allegiance which they owe…have at length proceeded to open and avowed rebellion…we strictly charge and command all our Officers, civil and military, and all others our obedient and loyal subjects, to use their utmost endeavours to withstand and suppress such rebellion…

- A Proclamation, by The King, for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition

Washington addresses an issue of indecency: Soldiers have been bathing in the river—naked—in full view of local civilians, including women. Washington tolerates bathing for health reasons but now prohibits it at or near the bridge, citing the “shameful” conduct as damaging to the army’s reputation.

Across the siege lines, Major General William Howe, commander of the British troops around Boston, accuses American soldiers of firing upon British officers during paroles, temporary truces usually arranged for humanitarian reasons or prisoner exchange.

The General does not mean to discourage the practice of bathing, whilst the weather is warm enough to continue it; but he expressly forbids, any persons doing it, at or near the Bridge in Cambridge, where it has been observed and complained of, that many Men, lost to all sense of decency and common modesty, are running about naked upon the Bridge, whilst Passengers, and even Ladies of the first fashion in the neighbourhood, are passing over it, as if they meant to glory in their shame

- Washington's General Orders

General John Sullivan’s brigade is undergoing reorganization, and preparations are made for a full muster tomorrow. Washington’s order directs the muster master general to begin precisely at 6 a.m., moving regiment by regiment, left to right along the lines. This administrative overhaul is part of ongoing efforts to impose structure on the army.

Jonathan Trumbull, governor of Connecticut, writes with updates on regional supply efforts. No new gunpowder has arrived, but the colony is working hard to smelt lead ore in Middletown and Woodbury.

Washington spends much of the day writing letters. To Major General Philip Schuyler in New York, he outlines an audacious plan to send a second force, under Benedict Arnold, through Maine to attack Quebec, a bold strategy to divide British forces in Canada.

To his cousin Lund Washington, he vents frustrations about Mount Vernon affairs—unfinished millwork, debts, and rumors that Virginia's royal governor might try to capture Martha. Though Washington doubts Dunmore would stoop so low, he asks Lund to prepare a safe refuge for her and his papers, just in case.

Washington dictates a blistering letter to British General Thomas Gage. Washington had previously appealed to Gage to treat captured American officers and civilians with humanity. Gage’s dismissive response—questioning the legitimacy of Washington’s command and American claims to authority—prompts this forceful reply. Washington warns that if British officers receive poor treatment going forward, it is only because Gage has set that precedent.

“I shall now, Sir, close my Correspondence with you, perhaps forever,” he writes.

You affect, Sir, to despise all Rank not derived from the same Source with your own. I cannot conceive any more honourable, than that which flows from the uncorrupted Choice of a brave and free Poeple—The purest Source & original Fountain of all Power.

- George Washington to Lieutenant General Thomas Gage

Washington issues the day’s General Orders. John Conner, of Captain Robert Oliver’s company, has been tried and found guilty of stealing a cheese from a fellow soldier, Richard Cornell.

Washington approves the court martial's sentence: 39 lashes on Conner’s bare back, to be administered publicly at the changing of the guard, “at the head of the two Guards” — an unmistakable warning to others.

Washington’s General Orders today emphasize accountability: Officers must muster troops regularly, keep accurate rosters, and ensure all arms and ammunition are properly stored. He assigns Ezekiel Cheever as Commissary of Artillery Stores and pushes for quick returns on all military supplies.

From Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin and the Committee of Safety write to inform Washington they’ve seized British uniforms and officers from a ship out of Cork. The captured officers will soon arrive under parole. Supplies are short, especially gunpowder, and the army must make do.

In his General Orders, Washington reports that Captain Eleazer Lindsey has been tried by a General Court Martial for abandoning his post, which was attacked shortly thereafter and overrun by the enemy. The verdict is firm: Lindsey is found unfit for command and is discharged from military service.

From Chelsea, Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin writes to report that men from British warships have fired on American positions, provoking small arms return fire. “Several of ther Ball Struck within a yard or two of me,” he writes.

Washington appoints several Brigade Majors and selects Edmund Randolph and George Baylor as his personal aides-de-camp. He also orders each regiment to report on troop numbers, ammunition, and desertions, warning that missing cartridges will be deducted from soldiers’ pay.

Across the river in Chelsea, Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin sends Washington his daily report: “I hope to be able tomorrow to forward … a letter from the Mr J.C. the Grocer.” The “Grocer” is John Carnes, a Boston merchant turned intelligence source who is funneling secret information to the Americans.

In his General Orders, Washington appoints Major Thomas Mifflin, an energetic Philadelphia Quaker, as Quartermaster General of the army. Mifflin is entrusted with the immense task of supplying the Continental troops. Stephen Moylan, the newly appointed Muster Master General, is instructed to distribute blank muster rolls so each captain can account for his men.

Washington also writes to Rhode Island’s Governor Nicholas Cooke, urging a covert strike on Bermuda’s powder magazine, a bold plan to seize desperately needed gunpowder.

General Thomas Gage writes Washington to respond to accusations of mistreating American prisoners. Gage claims British humanity surpasses that of the rebels, asserting that captured Americans have been better cared for than the King’s own troops. He warns that continued mistreatment will lead to “dreadful consequences.”

Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin reports from Chelsea of a skirmish that broke out around noon. His men fired on British boats near Charlestown Neck. Baldwin believes some enemy soldiers are killed. There are no American casualties.

Washington writes to the Massachusetts General Court, responding to a proposed expedition to invade Nova Scotia. Though he admires their zeal, such an incursion would be one of conquest, not defense, he argues, and would set a dangerous precedent. There is simply not enough ammunition to support such a move.

Meanwhile, from Cap-Français (in present-day Haiti), a young French officer named Lieutenant Desambrager offers his services and those of three companions to Washington. It’s a telling sign of the Revolution’s growing appeal to foreign volunteers.

Washington is deeply frustrated. Reports have reached him that some of his soldiers have been pillaging gardens and destroying fences near Watertown. He writes sternly: “Any Person who shall for the future be detected in such flagitious, wicked practices, will be punished without mercy.”

Washington writes a pointed letter to British General Thomas Gage, condemning the cruel treatment of American prisoners in Boston. Reports of wounded men confined with felons, denied food and medical care, compel him to warn: British captives will be treated the same unless conditions improve.

In his General Orders, Washington addresses a crisis: soldier pay. The army has gone weeks without wages. He directs paymasters to calculate what each man is owed as of August 1, promising full and fair payment as soon as funds arrive.

To the northeast, in the coastal town of Marblehead, local leaders are on alert. Two men — Lambert Bromitt and Benjamin Silsby — arrived by boat from Boston two days earlier, allegedly driven in by bad weather. But the Marblehead Committee of Safety is suspicious. They may be spies. The men are sent to Washington’s headquarters under guard.

In the day’s General Orders, Washington instructs commanders to report how many tents and blankets are still needed, especially for men who lost theirs at Bunker Hill. Washington also calls for the names of soldiers who distinguished themselves in that battle—he’s determined to reward merit with promotion.

He appoints John Goddard as Wagon Master General and issues detailed instructions to improve supply transport. In a letter to Governor Jonathan Trumbull of Connecticut, Washington warns that the British may be preparing to move toward New York.

Washington has grown frustrated with the number of soldiers claiming sickness to gain leave. He suspects some are abusing the system, possibly returning home to work their family farms while still drawing rations and pay from the army’s limited stores. Anybody caught doing so, he warns, will face severe punishment.

Washington also outlines the soldiers’ rations: one pound of fresh beef or salt fish, a pound of bread or flour per day, three pints of beans per week, a pint of milk when available, spruce beer or molasses, plus rice, salt, soap, and candles.

At Cambridge, Washington issues General Orders to impose discipline. Captain Samuel Kilton is found guilty of neglecting duty and publicly reprimanded at the head of his regiment. Washington authorizes each regiment to appoint a sutler to supply goods—but insists on fair prices and forbids officers from profiting.

Washington writes Joseph Palmer, Massachusetts entrepreneur and patriot, to decline appointing Palmer’s son as Quartermaster General of the army. He explains that spreading appointments across all colonies avoids regional favoritism.

Washington is troubled by a delicate situation: the proposed prisoner exchange for a man named Benjamin Hichborn, who has been captured by the British. Washington insists it must be handled formally to avoid weakening American credibility.

Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Loammi Baldwin reports from Chelsea. British floating batteries have shelled the ferry landing and burned buildings near the Mystic River. Some American militiamen, including Capt. Eleazer Lindsey, abandoned their posts during the attack—an infuriating sign of the army’s lack of discipline.

Washington commands that tomorrow, at 8 a.m., field officers from each brigade will elect representatives to help formalize the army’s officer ranks. This court will determine how to assign rank and number the regiments.

Washington also writes to James Otis, Sr., expressing concern over loyalist sympathizers entering American lines from Boston. He specifically mentions Mrs. Goldthwait, wife of the British barrack master, now detained in Malden.

Washington begins his day deeply troubled: The Continental Army is nearly out of gunpowder—only nine rounds per man remain. He urgently writes to Governor Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island, proposing a daring plan to seize powder from a British magazine in Bermuda. Washington also addresses the lack of clothing for his troops, requesting tow cloth and a hunting shirt pattern to create simple uniforms.

In his General Orders, he harshly reprimands soldiers for wasting ammunition by firing recklessly, warning that violators will be treated as enemies.

Reports have reached Washington that soldiers are seizing British goods during skirmishes and holding them privately. He sternly reminds his army: Any plunder taken from the enemy must be surrendered immediately to the commanding officer. If not, “severe punishment will follow.”

Washington convenes a Council of War, where he learns that the army has a shockingly low amount of gunpowder—not even half a pound per man. General John Sullivan remembers that, when Washington heard the news, “he did not utter a word for half an hour.”

Washington reviews two court-martial decisions. Captain Oliver Parker is cashiered for defrauding his men and misappropriating rations; Captain Christopher Gardner is dismissed for deserting his post. Washington approves both sentences, underscoring his commitment to order.

Meanwhile, General John Sullivan writes Washington from Winter Hill, Massachusetts, to report dangerously low stores: 19 barrels of powder, almost no musket balls, and no spare flints—just enough for one engagement.

In his General Orders, Washington commends Major Benjamin Tupper and his men for the daring raid yesterday on Lighthouse Island in Boston Harbor. He orders the prisoners marched to Worcester under guard. He also instructs each regiment to assign men to clean the encampments and maintain latrines, warning that poor sanitation could threaten the army’s health.

Elbridge Gerry writes Washington from Watertown: only 36,000 cartridges are available—far short of the 200,000 requested. The powder stores are dangerously low. Just 36 barrels remain.

Washington receives word of a successful American raid on Lighthouse Island, where Major Benjamin Tupper’s men captured British prisoners. Washington issues General Orders requiring detailed inventories of army provisions and officer rosters, striving to bring order to the new Continental Army.

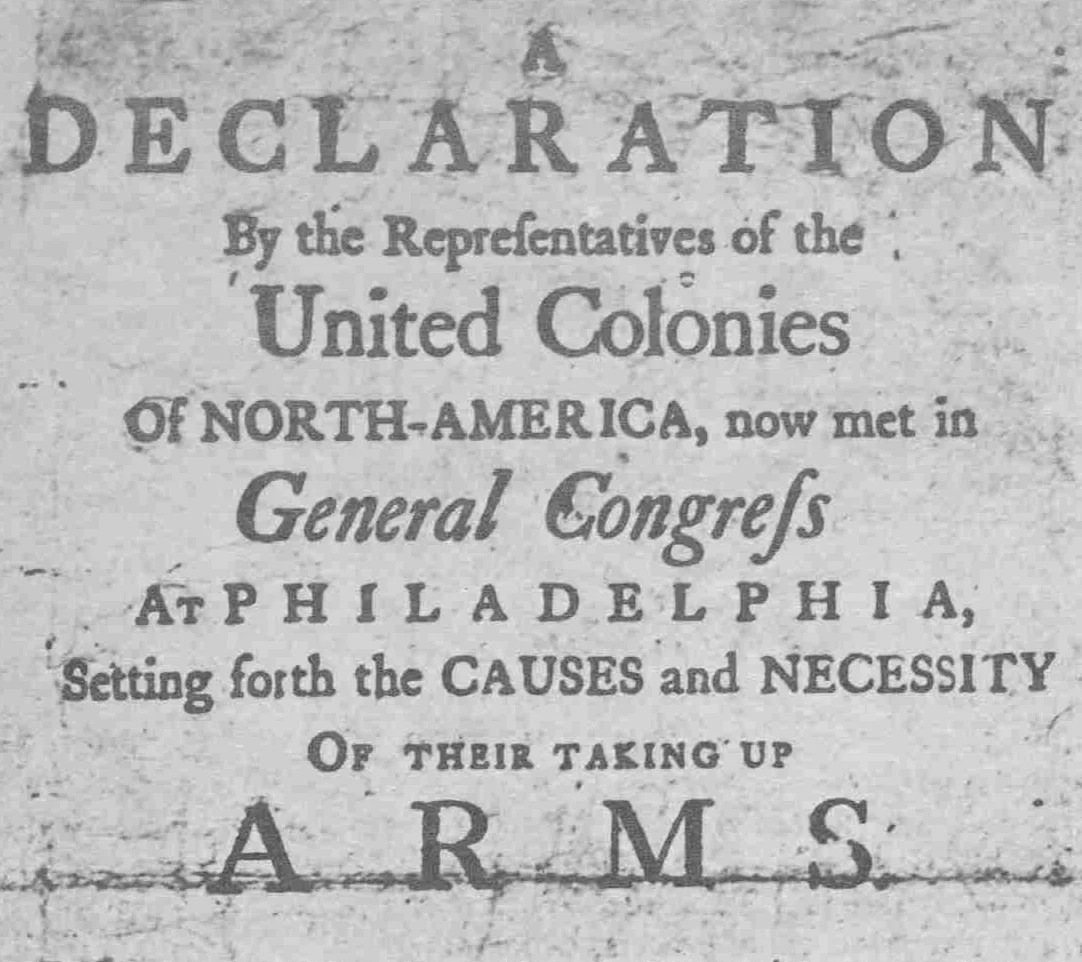

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress formally rejects a British reconciliation proposal from Lord North’s ministry. Addressed to private citizens rather than Congress itself, the offer is seen as an insult and is dismissed as insufficient.

Washington’s day begins amid uncertainty: Last night, he ordered riflemen to scout British fortifications. Discovered prematurely, they exchanged fire with the enemy just after midnight and returned with two prisoners. At daybreak, the alarm spreads. Volunteers assemble but Washington, wary of British cannons and naval support, calls them back to avoid unnecessary losses.

He issues General Orders appointing William Tudor as judge advocate and requiring regular training for drummers and fifers—part of a broader push for discipline.

Washington’s General Orders detail the outcomes of several military trials. He approves punishments: lashes for a soldier who forged an order to steal rum and another for robbing a surgeon. Others are acquitted.

Behind the scenes, Washington’s intelligence efforts deepen. Yesterday, his aide Joseph Reed briefed Lieutenant Colonel Loammi Baldwin on a covert plan to funnel intelligence from within Boston. A trusted contact named John Carnes, a grocer in the city, will pass along information via a chain of messengers.

Tensions are high in Boston, where British forces remain well-fortified. Washington issues stern General Orders demanding that surgeons from several regiments immediately submit overdue reports on the number of sick soldiers—an urgent concern as disease threatens the strength of his forces.

Washington also writes to Major General Philip Schuyler at Ticonderoga. He responds to Schuyler’s recent letters, warning him to remain vigilant against British attempts to enlist Native allies and sympathizing with the challenges of organizing undisciplined troops.

In his General Orders, Washington officially appoints John Trumbull, Jr., the son of Connecticut’s governor, as one of his aides-de-camp. Trumbull, who previously sketched enemy positions around Roxbury, has impressed the general with his drawing skills and military promise.

Washington also issues strict orders regarding British deserters—none are to be given rum before interrogation, after several arrived drunk last night. “It will be considered as a Breach of orders in any person, who gives Rum to Deserters, before they are examined by the General.”

Washington’s day is filled with urgent correspondence: British ships have left Boston—three warships and nine transports—and he warns Rhode Island’s Deputy Governor Nicholas Cooke of potential coastal raids. Washington suspects the British are desperate for fresh provisions and may target local islands.

His General Orders reflect the growing complexity of command. He urges officers to begin constructing winter barracks and clear the former home of Loyalist Andrew Oliver to expand the army hospital.

From his headquarters at Vassall House, Washington issues General Orders to address a growing problem: men who, having enlisted in one regiment, re-enlist in another—lured by bonuses or personal loyalties. To avoid being bogged down by these disputes, he directs that such matters be handled by brigade commanders through court-martials.

Washington writes a letter to his old friend George William Fairfax in England to correct likely British misinformation about the recent Battle of Bunker Hill. Washington reports that American losses were significantly lower than claimed.

In his General Orders, Washington reprimands officers and soldiers for leaving their posts without relief, and sentinels are warned not to stop generals. To fix this, Major Generals are ordered to wear broad purple ribbons for visibility. Washington also addresses filthy guardhouses and demands returns of the sick, seeking better sanitation and medical oversight.

John Hancock writes from Philadelphia: Congress is struggling to supply tents and shirts. But there is encouraging news—Georgia has joined the Continental Congress, and Patriots have captured a British powder ship.

With no uniforms to distinguish ranks, Washington issues orders for officers and enlisted men to wear colored cockades and cloth stripes as temporary badges.

Unbeknownst to Washington, betrayal festers within the ranks. On this very day, Dr. Benjamin Church—trusted patriot and member of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety—secretly writes to British intelligence, revealing American troop numbers, supply levels, and strategic positions. “Make use of every precaution or I perish,” he concludes.

From his headquarters, Washington issues sweeping General Orders: The army is to be divided into three grand divisions, each composed of two brigades with assigned posts and commanders.

Washington also receives detailed reports: Captain Joshua Davis submits a full inventory needed to outfit 100 whale boats—including oars muffled with sheep-skin for stealth. Captain Richard Dodge observes British boat traffic in Boston Harbor, noting dozens of transports filled with troops and horses shuttling between Boston and Charlestown.

Washington writes to John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, to underscore an urgent need: money. He renews his plea to Congress for funds to support the army. Washington writes two more letters to Hancock throughout the day, as more news arrives.

One such piece of news is that American troops have raided the Nantasket Peninsula, secured barley and hay, and burned down the Boston Light—a strategic lighthouse—to deny the British its use.

The day begins before dawn—too early in fact. Certain corps have sounded the Reveille prematurely. In the day’s General Orders, Washington instructs, “The Reveille is to beat when a Centry can see clearly one thousand Yards around him, and not before.”

Washington writes a lengthy and candid letter to his younger brother Samuel, describing both the military landscape and the emotional toll of war. “The Village I am in, is situated in the midst of a very delightful Country… A thousand pities that such a Country should become the theatre of War.”

John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress, writes Washington a letter introducing two young New Jersey men—Matthias Ogden and Aaron Burr. These are no idle visitors. Hancock clarifies that the pair come “not as Spectators, but with a View of Joining the Army & being Active during the Campaign.”