Both his choice of uniform and his equipment branded General Washington as an honorable and frugal leader during the American Revolution.

For Washington, outfitting for war was not just a matter of necessity or convenience; it was an argument asserting that Americans had the virtue and civility to govern themselves.

At the outset of the conflict, the then-called United Colonies had a profound image problem. To the mother country, Americans were spoiled children, provincial and naïve, and when it came to fighting, “poltroons & cowards.” Washington’s self-presentation through his uniform and material goods defined him as a man of honor, a leader who led by merit rather than ostentatious displays of wealth and power, served without pay, and was frugal with public funds. To see Washington at his campaign headquarters surrounded by his troops was to see one of “the most admirable spectacles in the world—the valiant and generous leader of a brave nation fighting for liberty,” gushed French diplomat the Marquis de Barbé-Marbois.

Now, the objects Washington owned during the Revolution tell a powerful story. They shaped his image as a citizen-leader and embodied the values of a fledgling nation.

1

Leather Trunk

A place to hold wartime correspondence

Arguably the most important parts of Washington’s baggage were the trunks that secured his official correspondence—the papers that would defend his character and actions before Congress and his contemporaries.

This half-tanned leather trunk was the first one used for this purpose. Purchased on April 4, 1776, as Washington and the Continental Army departed Boston on the first major campaign of the war, it was not exactly ideal in form for carrying papers, but it was the best that could be found at the moment. Washington’s oval copper nameplate was nailed over the previous owner’s initials.

In 1781, after five years of service, the trunk and its papers were delivered to Lieutenant Colonel Richard Varick, the recording secretary appointed by Congress to organize and classify all official wartime correspondence.

2

Military Sash

Symbol of rank, ultimately abandoned

Elected commander of the Fairfax Independent Company in the fall of 1774, Washington initially outfitted himself with the typical symbols of rank worn by English officers, including this red silk sash. These specialty items were in short supply at the time, and Washington’s agent secured the “only one” to be found in Philadelphia, a secondhand sash purchased at the discounted price of £5. Washington may have worn it while attending the Second Continental Congress in 1775, but by the time he took command of the Continental Army in July 1775, he had dropped it.

The decision was one of many refinements he would make to his and his officers’ uniforms over the course of the war.

3

Spyglass

The better to see British and American troop movements with

Handheld telescopes were crucial to George Washington’s ability to monitor troop movements. He acquired several during the war through purchase and as gifts and on one occasion, he sent one to an officer in preparation for covert communication via signal fire.

This handsome, three-draw, mahogany and brass spyglass by London optical instrument maker Henry Pyefinch was named in Washington’s will as “part of my equipage during the late War.” It featured achromatic lenses: compound lenses made of two different kinds of glass that corrected chromatic distortion of color wavelengths, resulting in a crisper and cleaner image. Pushing in or pulling out the draw barrels focused the instrument.

4

Smallsword

Symbol of rank, honor, and prowess

Washington wore this finely decorated 1767 silver-hilted smallsword on many dress occasions during the war. Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of Washington often display this sword, a detail that heightens their realism.

Originally acquired in the 1760s, the sword features a German blade and a London-made hilt with delicate piercing on the guard and pommel button, faceted bright-cut decoration on the knuckle bow, and elegant tracery engraved on the blade.

Washington is believed to have worn this sword for his greatest, final act of the war, when he resigned his commission before Congress in December 1783 and returned to civilian life.

5

Pistols

Ceremonial, as well as practical

Over the course of the war, Washington acquired several pairs of pistols through purchase, capture, and gift.

These smoothbore flintlock pistols date to circa 1780 and bear the mark of lockmaker William Woolley of Bilston, England. They feature brass barrels, lockplates, sideplates, and butt caps, with the additional flourish of silver wire inlay on the tang.

In the 19th century, a later generation of owners cut down the barrels and a misfiring resulted in the partial destruction of one.

6

Field Bedstead

A foldable cot frame that came up short

Washington acquired this field bedstead in Massachusetts on October 3, 1775, just a few months after taking command, and used it throughout the war in his sleeping tent.

The plain bedstead exhibits the ingenious design that characterized British campaign furniture. The posts and legs fold up, and the rails are hinged to fold like an accordion, collapsing into a form that could be bundled into a leather portmanteau and easily transported. It may have been a little short for the General’s estimated 6'2'' frame (it was just six feet long by three feet wide), but when fitted out with bedding, canopy, and curtains, it offered hope for a relatively comfortable night’s sleep in the field.

7

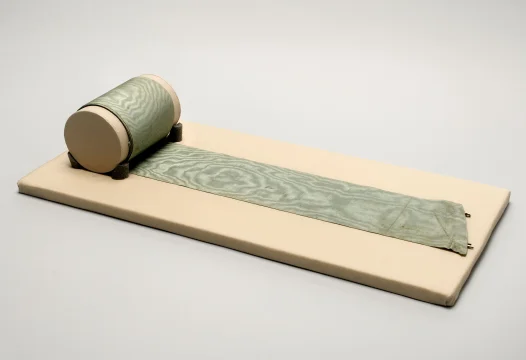

Blue Ribbon

A changing look

This delicate blue silk ribbon is a remnant of Washington’s wartime appearance, having been worn by him between 1775 and 1780.

Upon taking command of the loosely constituted Continental Army, Washington needed a simple way to make sure independent-minded men from across the colonies could tell who was in charge. In his General Orders of July 14, 1775, Washington designated that a blue ribbon be worn by the commander in chief, purple by major generals, pink by brigadier generals, and green by aides-de-camp.

It may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but it sent mixed messages, confounding soldiers and outside observers alike, who thought the system contradicted the goals of the cause. The ribbons resembled those worn by the nobility and members of orders of chivalry in Europe. In England, blue silk ribbons were synonymous with loyalty to the crown and were worn by the elite Knights of the Order of the Garter.

The Marquis de Barbé-Marbois saw Washington’s ribbon as an “unrepublican distinction.” When Washington dispensed with the ribbon system in 1780, Barbé-Marbois commended the change, noting that Washington’s uniform then appeared “exactly like that of his soldiers.”

Washington gave the ribbon to painter Charles Willson Peale, who preserved it for posterity, even while his portraits of the General from 1780 onward presented his new, ribbon-less look.

8

Camp Chest

Cooking and dining while on the go

Washington’s camp equipage included several canteens, or traveling chests and leather packs for transporting lightweight cooking equipment, food, and spirits when on the move.

This example contains tinned sheet iron plates, camp kettles with detachable wooden handles, a folding gridiron, and cutlery. The dishes endured heavy use, and in 1779, Washington noted: “[M]y plates and dishes, once of Tinn, now little better than rusty iron, are rather too much worn for delicate stomachs in fixed and peacable quarters, tho they may yet serve in the busy and active movements of a Campaign.”

Washington procured sets of ceramic dishes to use during winter quarters and when entertaining at headquarters.

9

Sleeping and Office Tent

A moveable field headquarters

Eager to get on campaign, Washington acquired his first set of headquarters tents made of strong linen in the spring of 1776. In a letter to Colonel Joseph Reed, he wrote, “I cannot take the field without equipage, and after I have once got into a tent, I shall not soon quit it.”

Washington typically used his field headquarters for seven to eight months of the year—roughly from May to December. After two years of hard campaigning, he replaced the first set of tents with new ones in 1778.

Thanks to the remarkable efforts of numerous individuals, most of this second wartime tent complex survives, including the sleeping and office tent, now held by the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

The relative plainness and simplicity of the tent, in contrast to the elaborate setups of warring European monarchs, became emblematic of Washington’s virtue. His commitment to living in a tent, personally identifying with the hardships of his troops, demonstrated he was one of them and worthy of their respect.

10

Camp cups

Ruggedly elegant tumblers of good cheer

Dining with General Washington was a formal affair, equivalent to a state dinner when members of the government and foreign dignitaries were present.

Silver camp cups brought an air of elegance to the otherwise modest table settings. Philadelphia silversmith Richard Humphreys made this camp cup engraved with Washington’s crest as part of a larger set. Among the guests who recalled drinking from them was one English visitor, who, arriving ill, noted: “The General … made me drink three or four of his silver camp cups of excellent Madeira at noon, and recommended to me to take a generous glass of claret after dinner, a prescription by no means repugnant to my feelings.”

Washington’s cure worked like a miracle. The visitor claimed, “I continued my journey to Massachusetts, without ever experiencing the slightest return of my disorder.”

About the Author

As Mount Vernon's curator of Fine and Decorative Arts, Amanda Isaac cares for a collection that ranges from George and Martha Washington’s personal effects and household furnishings to the fine art, historical relics, and commemorative objects that embody their multifaceted legacy.

She holds an M.A. from the University of Delaware’s Winterthur Program in Early American Culture and a B.A. from the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Washington's Military Equipment

General Washington's military service spanned several decades of his life. Explore more of his military equipment—from before, during, and after the Revolution.