Thomas Jefferson was a key political figure in the American Revolution, later serving in the Washington and Adams administrations before being elected as the third president of the United States. Perhaps most famous for his authorship of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson politically advocated for natural rights, limited central government, and religious freedoms. He shared a unique friendship with George Washington, one built on personal similarities and political views. However, political tensions with the first president grew into partisan factions when Jefferson served as his Secretary of State.

Early Life

Born in 1743 to parents Peter and Jane Randolph Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson, like Washington, was born into the emerging gentry class of Virginia. Families such as Jefferson’s began to establish themselves further from the coastal regions of the state. Despite this, Jefferson received a formal, classical education. After his father’s death, he inherited landed near present-day Charlottesville, Virginia where he would construct Monticello in 1772. At eighteen, he attended William and Mary and studied law.

Like Washington, he felt the financial constraints of a deceased father, and in 1772 he also married a wealthy widow, Martha Wayles Skelton. Together they shared six children before her death in 1782, with only two reaching adulthood. They moved to Monticello. In his lifetime, Jefferson enslaved over six-hundred people at Monticello and other properties. Later, his friendship with George Washington involved correspondence around sharing reading materials about new husbandry and their ongoing projects.1

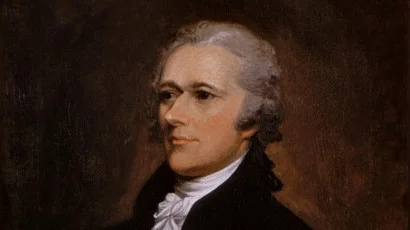

Park Collection, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Role in the American Revolution

Having gained prominence as a lawyer, Jefferson served in the House of Burgesses from 1769 to 1774. Early in his political career, he was interested in policies that limited the power of royal governors and officials. With the passage of the Intolerable Acts, his disapproval for the royal government grew stronger, and he instigated the boycott of British goods through his political writings. As a member of the Second Continental Congress, Jefferson was recognized for his brilliant writing, expressed most clearly in the Declaration of Independence. Although one of the youngest delegates, he began to cultivate political friendships with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. Washington began to correspond with Jefferson more frequently as the war turned south, warning him to ensure the Virginia militia had supplies and could mobilize further south. Washington wrote this would be “extremely precarious” to accomplish.2 During the American Revolution, Jefferson became involved in the formation of the Virginia state government and the in authorship of their state constitution. As he served in Virginia's assembly, he ended primogeniture, entail, and established freedom of religion. Later, he became Governor for a one-year term.

Public Service After the American Revolution

Jefferson was selected as Virginia’s delegate in the Confederation Congress, and he helped draft legislation that later was modified as the Northwest Ordinance to promote American settlement Ohio River Valley. In 1784, he was appointed ambassador to France. In this role, he relied on his friendships with Adams and Franklin who had also served abroad. He often transmitted correspondence between Marquis de Lafayette and Washington.3 In France, he shaped the foreign policy of the nascent United States, and navigated the beginnings of the French Revolution. He also traveled to London to broker relations with the British. While in Europe, he supported the ratification of the Constitution through correspondence.

As Secretary of State and Vice President

After George Washington was elected president, Jefferson returned to the United States in November 1789 to serve as his Secretary of State on Washington’s cabinet. His troubles with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton began almost immediately. He questioned Hamilton's plan for funding and considered the Bank of the United States unconstitutional. As the French Revolution grew more violent, Jefferson continued to support an alliance with France against Hamilton who favored closer ties with Great Britain. These tensions only mounted with scandals such as the Genet Affair, in which members of the French Revolutionary government attempted to undermine Washington’s desires for neutrality. Given these disagreements, Jefferson resigned from Washington's cabinet at the end of 1793. Receiving his resignation, Washington wrote, “your integrity and talents, and which dictated your original nomination, has been confirmed by the fullest experience; and that both have been eminently displayed in the discharge of your duties.”4

Although Washington advocated against the formation of political parties in his Farewell Address, factions continued to form. Amid a partisan divide over key issues such as banking and foreign relations, Jefferson became the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party. Running on this platform for president in 1796, he lost to federalist John Adams. He was selected as his Vice President and their relationship became extremely strained. Adam’s presidency was unpopular due to disruptions to trade like the Quasi-War and scandals like the XYZ Affair. Partisan politics heightened with press attacks between the growing political parties, and this strained Jefferson’s relationship with George Washington further. After Washington’s death in 1799, he was particularly disdained by Martha Washington. Jefferson was elected President in 1800, after the House of Representatives declared broke the tie in the electoral college between Jefferson and Aaron Burr.

Presidency

Jefferson was inaugurated as president in 1801. In his inaugural address, he called Washington “our first and greatest revolutionary character.”5 His two-term presidency began the over two decades of Democratic-Republican power in the office, with candidates from this party serving as president through the election of 1824. Despite this partisan control of the presidency, Jefferson and others did not majorly alter systems put in place by the Federalist Party, including the National Bank.

As president, Jefferson approved of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, nearly doubling the size of the United States. Although criticized as a loose interpretation of the Constitution, Jefferson deemed in necessary and it supported his agrarian vision for the United States. He also managed challenges in foreign affairs, including the Barbary War which disrupted shipping to Europe. Additionally, as warfare between Britain and French escalated, Jefferson passed the Embargo Act of 1807 to assert American neutrality in the conflict, which he later repealed in 1809.

Later Life and Legacy

Jefferson remained politically influential after his presidency, remaining close with future presidents James Madison and James Monroe. He mended past relationships, such as with John Adams. Valuing education, he was pivotal in establishing the University of Virginia. Marquis de Lafayette visited Jefferson on his 1824-1825 American Tour. In 1826, Jefferson died and was celebrated for his contributions as the author of the Declaration of Independence and as president. However, his position as a slaveholder despite his political views on ending the international slave trade effected his legacy.

When serving as the American ambassador to France, Jefferson’s daughter was accompanied by an enslaved servant named Sally Hemings. Hemings was fourteen and the half-sister of Jefferson's deceased wife. Hemings was previously enslaved by her family, and was inherited by Thomas Jefferson. At this time, Jefferson likely began a sexual relationship with Hemings, with whom he would father six children. Jefferson formally and informally freed their children who survived adulthood and other members of the Hemings family, and Sally was informally freed by Martha Jefferson Randolph after Jefferson’s death. However, after his death, others he enslaved faced family separation through sale to pay off his large debts.

Originally Researched by Mary Stockwell, Ph.D., Revised by Zoie Horecny, Ph.D., 27 August 2028

Notes:

1. “George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 13 May 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives,

2. “George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 15 April 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

3. “George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 3 March 1784,” Founders Online, National Archives.

4. “George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 1 January 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives.

5. “III. First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1801,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Brodie, Fawn M. Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History. W.W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life. New York: Penguin Press, 2010.

Chervinsky, Lindsay M. The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution. Harvard University Press, 2020.

Cogliano, Francis D. A Revolutionary Friendship: Washington, Jefferson, and the American Republic. Harvard University Press, 2024.

Cogliano, Francis D. Emperor of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson’s Foreign Policy. Yale University Press, 2014.

Ferling, John. Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Fleming, Thomas. The Great Divide: The Conflict Between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation. Da Capo Press, 2015.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. The Hemingses of Monticello. W.W. Norton, 2009.

Hayes, Kevin J. The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Malone, Dumas. Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962.

Jefferson: Writings. Ed. Merrill D. Peterson. New York: Library of America, 1984.