![Portrait of Sir Henry Clinton, by Andrea Soldi, ca. 1762-1765. [1964.70.1]. Courtesy American Museum in Britain, Bath, U.K.](https://mtv-drupal-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/files/resources/sirhenryclinton2.jpg?VersionId=iCZgen05LatR_UfDZAFLRg4d0WEu5nhw)

The only son of a British Admiral, Sir Henry Clinton was raised in pre-revolutionary America. In service to the British during the American Revolution, he began commanding troops in Boston in 1775 under Generals Thomas Gage and William. His military insights were often ignored by his superior officers, but he proposed and led the double envelopment plan that routed the Continentals on Long Island in 1776 as General Howe’s second in command. Clinton became Commander in Chief of the British Army in America in upon William Howe’s recall in 1778 and led his forces in the battles of Monmouth and Charleston. Though an able tactician, he had many critics. His failure to provide timely aid during the doomed Yorktown campaign and led to his resignation in 1781.

Personal Life

Clinton was the only son to an Royal Navy officer of an aristocratic family. His father served as a Royal Governor of New York from 1743-1753. As a young man, Clinton rose to the ranks of the British Army in the Seven Years’ War, serving in Germany in the 1760s. Clinton was a senior officer in Germany in the 1760s, serving as aide de camp to the Prince of Brunswick from 1760 to 1762. He was known as member of the “German School” of continentally experienced British officers. Fluent in French, Clinton was the most cerebral of all the British Generals in America.

In 1767, Clinton married Harriet Carter, age twenty, half his age. They lived together only five years. She died tragically in 1772, eight days after the birth of her fifth child. He was described as depressed after her death, and eventually lived out his life as an unmarried widower. He never held a job outside of the Army until he served in Parliament from 1774 to 1784.

Service to the British in American Revolution from 1775 to 1777

He arrived to Boston in 1775, serving under Generals Thomas Gage and William Howe at Bunker Hill with some distinction. Clinton favored a peaceful settlement on almost any terms. He saw war in America for Britain as a business, not a cause. Instead of taking and holding large rebel cities like New York and later Philadelphia, Clinton believed the decisive point to pursue was George Washington and the movements of the Continental Army, justifying an energetic and perhaps costly strategy. General Howe disagreed.

By late 1776, despite his stellar performance during the New York campaign advising plans for the Battle of Long Island, Clinton realized his relationship with General Howe had broken down over personal differences. He returned to England determined to resign his commission. King George III offered him a knighthood if he would stay he retained his position. Clinton reluctantly agreed, but upon his return to New York in July 1777, little had changed. He continued to disagree with his superiors strategically.

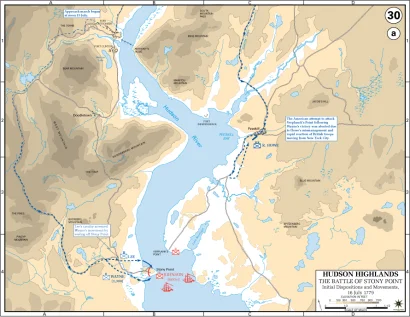

If General Howe simply followed the original plan for the campaign of 1777 and marched up the Hudson to link up with British General John Burgoyne (as Clinton strongly favored), the results for the British at the Battle of Saratoga could have been victorious. Instead, Howe marched on Philadelphia and ultimately was relieved of his command for this error. In this engagement, Clinton led a smaller force up the Hudson, but could not break through past Albany in time to relieve Burgoyne.

As Commander in Chief of the British Army

When France entered the war on the American side in February 1778, Clinton sensed he would never have the men, the ships, or the will to prevail over Washington by force. Given the shortcomings of others’ strategies, Clinton was appointed as the Commander in Chief. Upon his promotion to Commander in Chief in May 1778, Clinton found himself matched directly with his temperamental opposite in Washington. In his tenure as Commander in Chief, he often communicated with Washington, often about matters concerning the conditions of prisoners of war and prisoner exchanges.1

In 1779, in alignment with the King’s wishes, Clinton responded to the French challenge by pursuing a Southern strategy that sought to employ modest numbers of British troops in the southern colonies where it was hoped loyalist sympathies ran strongest. Clinton personally led 8,700 troops in a successful assault on Charleston, South Carolina, resulting in the capture of the city on May 12, 1780. His forces took over 3,300 continental and militia troops prisoner (including seven generals), the worst Continental Army defeat of the war. Washington wrote to Clinton, condemning the behavior of the British, writing, “I wish I could agree in opinion with you on the spirit which actuates your Officers in Southern command….They not only profess a flagrant breach of the capitulation of Charles Town and a violation of the laws of nations; but under whatever forced description the unhappy objects of the severity are placed, it is in a form and carried to an extreme at which humanity revolts.”2

Initial pacification efforts and amnesties seemed to quell rebellion throughout South Carolina, but over-confidence on Clinton’s part led to a final proclamation on June 3 requiring those seeking protection as loyal subjects to take up arms in support of Britain. This inflamed patriot sympathizers throughout the colony and led quickly to armed insurrection. Clinton left South Carolina in June with upheaval spreading and ordered his second in command, Lord Charles Cornwallis, to stay in South Carolina and attempt to solve the problem. Cornwallis essentially ignored this directive and began his own overland campaign into the interior of South Carolina and invaded North Carolina in 1781.

Constantly fearful of an attack by Washington on the weakened garrison at New York (having given up a net 10,000 plus men to other theaters) and harassed by superior numbers of French naval forces off the coast, Clinton was reluctant to dispatch additional troops to Cornwallis in the Carolinas and Virginia in late 1780 and 1781. Tensions mounted as communications frayed between commanders. Given Clinton’s hesitation to resign after the successful British Siege of Charleston, communications continued to break down resulting in the catastrophe at Yorktown leading to British surrender.

After the American Revolution

Clinton known throughout the service as insightful, but diffident, frequently quarrelsome, impulsive and a loner. Few subordinates liked working for him. Still, he held the confidence of King and Cabinet throughout his service in America. After British surrender, Clinton was relieved. He returned to England and spent the rest of his life defending his actions in America. He was appointed to serve as the governor of Gibraltar, but he died in 1795 before he could assume the role.

Andrew R. Bacas, George Washington University, updated by Zoie Horecny, 25 June 2025

Notes:

1. “From George Washington to General Henry Clinton, 20 November 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. “From George Washington to General Henry Clinton, 16 October 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Clinton, Sir Henry, Edited by William B. Wilcox, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

Doughty, Robert A., Ira D. Gruber et. al., Warfare in the Western World: Military Operations From 1600-1871, Lexington, Massachusetts: D. C. Heath and Company, 1996.

Ferling, John, The Ascent of George Washington, New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009.

O’Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of Empire, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Wilcox, William B., Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964.