Henry Lee III, also referred to as "Harry Lee," was a celebrated officer in the American Revolution. Serving in both the northern and southern theater of the war, he was known for his guerrilla styled tactics and for his skills given the moniker “Light-Horse Harry Lee” for which he was well known. After the war he continued with public service as a Federalist. Born into a well-connected Virginian family, he shared meaningful political and social connections to George Washington.

Early Life and Service in the American Revolution

Henry Lee III was born in 1756 to Lucy Grymes Lee and Henry Lee near Dumfries, Virginia. His mother had socialized with George Washington before her marriage, and both his parents had deep ties to colonial Virginia. Lee began his career by studying to be an attorney at Princeton University in 1773. However, the coming of the American Revolution brought Lee to serve under Washington with great distinction.

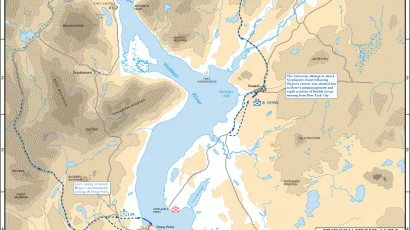

After commissioning as a captain in 1775, Lee was subsequently promoted to a major in the Continental Army with command of a small irregular corps known as Lee's Legion. Known for exhibiting excellent equestrian talent, Lee earned the name of "Light-Horse Harry Lee" before receiving the only gold medal for an officer under the rank of general for his surprise maneuvering at Paulus Hook, New Jersey on August 19, 1779. Although a successful raid, he was court-martialed against Washington's wishes for his bold conduct, and later acquitted of wrongdoing. Washington promoted Lee to Lieutenant Colonel in 1780, and was dispatched to the southern theater of war.1 Arriving to South Carolina, he worked will with local officers such as Francis Marion. He served and led forces in notable battles including the Battle of Guilford Court House and the Battle of Eutaw Springs. Afterwards, American forces advanced towards Virginia, and he was present for the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown resulting in American victory.

Life After the American Revolution.

Immediately following the American Revolution, Lee married Matilda Ludwell Lee and they had three children. After her death in 1790, he married Anne Hill Carter and they shared six children, including Robert E. Lee.

The connection between Washington and Henry Lee continued after the war as Lee remained active in public life. Lee served as a delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress from 1786 to 1788 when the government was transitioning to a new nation under the Articles of Confederation. Similar to Washington, Lee joined the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternity of Revolutionary War veterans. In 1786, Washington gave Lee money to purchase a set of blue Fitzhugh bordered china with the Society of Cincinnati motif of Fame holding an eagle to commemorate their membership.

Lee returned to military service when he accompanied Washington to help quell the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania in 1794. Washington lauded his efforts to his country, writing him, “No citizens of the United States can ever be engaged in a Service more important to their Country.”2 Later in his presidency, Washington chose Lee to serve as an alternate U.S. Army major general for Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Henry Knox from 1798 to 1800. Lee continued his political career from 1799-1801, serving as a Federalist Congressman from Virginia.

After Washington's death, Lee addressed the House and Senate and succinctly synthesized Washington's legacy to his contemporaries as the man, "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his country."3 Congress asked Lee to deliver the national funeral, which set the tone for other orations honoring the first president. Lee changed the earlier statement slightly to state, "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen." Lee prescribed that citizens should emulate Washington's life example so that allowing character to grow and endure: "Be American in thought, word, and deed—thus you will give immortality to that union."4

Later Life and Death

As Democratic-Republicans rose to power with the election of Thomas Jefferson, Lee retired from politics in 1801. However, with growing tensions with Britain he was appointed to organize the Virginia militia in 1808. Economic downturn disrupted his return to private life and he was in debtors’ prison for a year before moving to Alexandria, Virginia. He continued to struggle to pay off his debts, especially in relation to land speculation. He hoped for a commission in the War of 1812, but did not receive one. In 1812, he was injured in an attack on a Federalist newspaper in Baltimore, sustaining injuries he suffered for the rest of his life. For several years, he sought treatment for in the Caribbean. He died in 1818 on his return voyage, cared for by Louisa Shaw, the daughter of Nathanael Green, in Cumberland Island, Georgia.

Meredith Eliassen Reference Specialist, Special Collections Department J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University, updated by Zoie Horecny, PhD, 18 August 2025

Notes:

1.“George Washington to Major Henry Lee, Jr., or the Officer Commanding His Corps at Burlington, N.J., 30 March 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. “George Washington to Henry Lee, 20 October 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives.

3. Columbian Sentinel and Massachusetts Federalist, 28 December 1799.

4. Henry Lee, A Funeral Oration on the Death of George Washington at the Request of Congress (Philadelphia: John Hoff, 1800), 19-20.

Bibliography:

Detweiler, Susan Gray. George Washington's Chinaware. New York: Herry N. Abrams, 1982.

Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency, George Washington. New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 2004.

Lee, Henry. A Funeral Oration on the Death of George Washington at the Request of Congress. Philadelphia: Printed by John Hoff, 1800.

Lee, Henry. Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States. Philadelphia: Printed by Bradford and Inskeep, 1812.

Nagel, Paul C. The Lees of Virginia: Seven Generations of an American Family. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Royster, Charles. Light-Horse Harry Lee and the Legacy of the American Revolution. Louisiana State University Press, 1994.