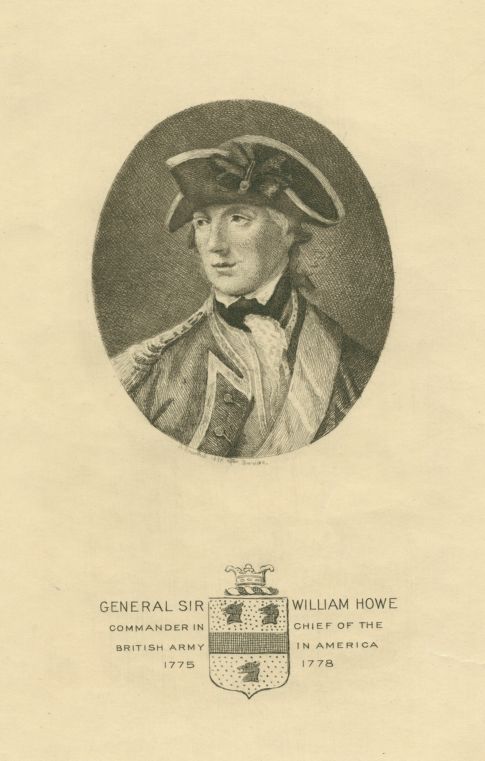

From October 1775 to May 1778, General Sir William Howe served as the commander in chief of the British military land forces sent to quell the American Revolution. Despite winning every battle in which he commanded against General George Washington, Howe was unsuccessful in ending the rebellion. Historians have studied and debated his failure ever since. After strategic miscalculations and frustrations with the British government, he resigned his post in the spring of 1778. One author offers an estimation that in Washington, Howe had an opponent “who possessed unusual tenacity … for denying the British the full fruits of victory.”1

Early Life and Military Career

William Howe was born August 10, 1729 into a prominent and well-connected family. His parents were Emanuel Scrope Howe, second viscount Howe, of Langar Hall, Nottinghamshire and the German-born Mary Sophia Charlotte von Kielmansegg.2 After a rudimentary education by private tutors and four years at Eton College, William followed his two brothers into military service.3 His family purchased a cornet’s commission in the Duke of Cumberland’s light dragoons in late 1746, a common practice at the time.4

By 1757, he had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel commanding the 58th Regiment of Foot and saw extensive service in Canada, Europe, and the Caribbean during the Seven Years’ War.5 In this conflict, William Howe earned a glowing reputation as a courageous officer who was respected by his soldiers.6 During the Siege of Quebec, as an example, he led an advance team up the sheer cliffs of the Heights of Abraham allowing General James Wolfe’s army to secure Quebec and ultimately Canada for Great Britain.7

In the years after the Seven Years’ War, William Howe continued to climb the ranks in the British Army, and by 1773, held the rank of Major General.8 He had also assumed a deceased brother’s seat in Parliament in 1758, placing him closer to the political center of his country.9 As tensions mounted between Britain and its North America colonies after the Stamp Act crisis, Howe publicly opposed the administration’s policies. Nevertheless, he was on the short list of general officers being considered for command in North America during the winter of 1774–1775. After seeking advice from his cabinet, King George III interviewed Howe and was satisfied with his military opinions enough to dispatch him to Boston as second-in-command in the early spring of 1775.10

British Service in the American Revolution

Howe and a task force of troops and supplies arrived in Boston on May 25, 1775. They were met with news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, as well as the reality of being outnumbered and surrounded. The commander in chief of the British Army in America, Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, resolved to counterattack the American militia forces on Breed’s Hill and dispatched General Howe to personally led the vanguard at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.11 Although the British Army won the day, it was at great cost with almost half of their troops killed or wounded. The ministry lost faith in General Gage with this loss and recalled him to London. William Howe was named “Commander-in-Chief of all His Majesty’s Forces” in North America “lying upon the Atlantic Ocean, from Nova Scotia on the North to West Florida on the South” several weeks later.12

The long months of stalemate in Boston were ended due to the extraordinary efforts of Colonel Henry Knox with the securing and placement of heavy artillery on Dorchester Heights in early March 1776. Threatened with destruction, Howe evacuated the city on St. Patrick’s Day. After reorganizing his forces in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Howe was joined with reinforcements and a naval fleet led by his brother, Vice Admiral Lord Richard Howe. The two set out for New York with warmer weather to take possession of the city and establish their headquarters.13

The Howe Brothers were also assigned by the home government as peace commissioners. After the Continental Congress declared independence, William Howe sent his adjutant general to meet with General George Washington. The meeting, according to a member of congress “terminated in nothing” for Washington believed that the citizens of the United States of America were only “defending our just rights.”14 Thereafter, General Howe opened the campaign of 1776 by trouncing the Continental Army at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776. He followed up with partial victories at Kip’s Bay, Harlem Heights, Pell’s Point, and White Plains over the next two months. In all of these actions, Howe practiced restraint and moved cautiously to preserve his resources to allow for a peaceful reconciliation. With the taking of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, the crown’s military forces secured much of the region of New York City for its headquarters. The campaign was assumed to be over, but when George Washington gained surprise victories at Trenton on December 26, 1776, and Princeton on January 3, 1777. American morale was restored and the British conciliatory approach folded.

General Howe, now Sir William Howe, as he had been appointed a Knight of the Bath for his victory at Long Island, spent the start of 1777 planning and preparing for a campaign to seize Philadelphia and force General George Washington into a battle. This operation began in the late summer when Howe moved his troops by sea and landed in Head-of-Elk, Maryland, some fifty miles southwest of Philadelphia. Washington met him on his march on September 11, 1777, and after a long and hard-fought battle, the British emerged as the victors of the Battle of Brandywine. Howe afterwards captured Philadelphia, and on October 4, 1777, repulsed an attack by Washington at the Battle of Germantown. In an uncommon and gracious act during the ugliness of warfare, General Washington returned a dog found by members of the Continental Army to the British lines, “which accidentally fell into his hands, and by the inscription on the Collar appears to belong to General Howe.”15

General Howe’s Philadelphia campaign and his failure to appropriately support Lieutenant General John Burgoyne’s expedition in upstate New York, led to a calamitous defeat for the British at the Battles of Saratoga, on September 19 and October 7, 1777. This loss, along with his frustration from unfulfilled requests for additional resources, and increasing criticism from the ministry, caused General Howe to resign his post just two weeks later. With the slowness of crossing the lengthy Atlantic Ocean, Howe would not learn that the King accepted his resignation until April of 1778.16 After a grand farewell gala in Philadelphia on May 18, 1778, Howe sailed for England.17 He was replaced by General Sir Henry Clinton.

Later Life and Death

Met with resentment from the government, General Sir William Howe began preparing to defend his conduct in Parliament. The scrutiny of a formal hearing in 1779 and an ensuing informal pamphlet war caused him to lose seat in the House of Commons in 1780.18 Although Howe never commanded in the field again, he continued to receive military promotions and political appointments once his enemies in the government were out of office. He was made Lieutenant General of the Ordnance in 1782, as well as being appointed to the King’s Privy Council.19 In 1793, he was promoted to full general and held various home commands in the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars.20 On the death of his brother Richard in 1799, Sir William Howe succeeded to the viscountcy, becoming the 5th viscount Howe. He retired from the army due to ill health in 1803, but served as governor of Berwick-upon-Tweed, from 1795 to 1808, and then Plymouth, from 1808 until his death on July 12, 1814. He was laid to rest at Twickenham on 22 July 1814.21

Samuel K. Fore

Notes:

1. Troyer Steele Anderson. The Command of the Howe Brothers During the American Revolution. (New York & London: Oxford University Press, 1936), p. 339.

2. Obituary in The Morning Post (London, England) Thursday, July 14, 1814; George E. Cokayne, et. al., eds. The Complete Peerage, or a History of the House of Lords and All Its Members from the Earliest Times... Vol. VI: Gordon to Hurstpierpont. (London: The St. Catherine Press..., 1926), pp. 596-599.

3. Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh, ed. The Eton College Register, 1698-1752. (Eton: Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co., 1927), p. 184.

4. Obituary in The Morning Post (London, England) Thursday, July 14, 1814; Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy. The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire. (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 88-89.

5. Great Britain. War Office. By Permission of the Right Honourable The Secretary at War. A List of the General and Field-Officers, As They Rank in the Army. A List of Officers in the Several Regiments of Horse, Dragoons and Foot, &c. on the British Establishment... (London: Printed for J. Millan..., 1757), p. 12; Ira D. Gruber. The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. (New York: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va. [by] Atheneum, 1972), pp. 56-57.

6. James Wolfe to John Parr, Dec. 6, 1758, quoted in Willson, Beckles. The Life and Letters of James Wolfe. (New York: Dodd Mead & Co., 1909), pp. 404-405; Major Philip Skene, Jan. 23, 1775, to Lord Dartmouth. Abstracted in Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Fourteenth Report, Appendix, Part X. The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth. Vol. II: American Papers. (London: [H.M.S.O.], 1895), p. 262.

7. Fred Anderson. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), pp. 353-354 & 357.

8. Great Britain. War Office. By Permission of the Right Honourable The Secretary at War. A List of the General and Field-Officers, As They Rank in the Army. A List of Officers in the Several Regiments of Horse, Dragoons and Foot, &c. on the British and Irish Establishments;... (London: Printed for J. Millan..., [1773]), p. 3.

9. John Brooke. “Howe, Hon. William (1729-1814). History of Parliament Online.” The History of Parliament: British Political, Social & Local History. Last modified 2020. Accessed August 14, 2025.

10. Ira D. Gruber “George III Chooses a Commander in Chief,” in Arms and Independence: The Military Character of the American Revolution, Hoffman, Ronald & Peter J. Albert, eds. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984), pp. 166-190.; Lord Barrington, 3 Feb. 1775, to Lord Dartmouth. Abstracted in Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Fourteenth Report, Appendix, Part X. “The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth. Vol. II: American Papers” (London: [H.M.S.O.], 1895), p. 266; John Fortescue, ed. The Correspondence of King George the Third from 1760 to December 1783… Vol. III: July 1773-Dec. 1777. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1927), p. 195.

11. John Burgoyne, Boston, to William Hervey, June 14th 1775 in De Fonblanque, Edward Barrington, ed. Political and Military Episodes in the Latter Half of the Eighteenth Century: Derived from the Life and Correspondence of the Right Hon. John Burgoyne,... (London: Macmillan & Co., 1876), p. 140.

12. The Earl of Dartmouth, [Westminster,] to Major General Sir William Howe, 2d August 1775. Nos. 24 & 25 in Dorchester, Guy Carleton, and Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. British Headquarters (Sir Guy Carleton) Papers, 1747 (1777)-1783. (Washington, D.C: Recordac Corp., 1957).

13. Troyer Steele Anderson. The Command of the Howe Brothers During the American Revolution. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936), pp. 120-127.

14. Admiral Richard Viscount Howe & General William Howe Declaration of July 14, 1776. No. 147, Dorchester, Guy Carleton, and Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. British Headquarters (Sir Guy Carleton) Papers, 1747 (1777)-1783. Washington, D.C: Recordac Corp., 1957; Charles Carroll of Carrollton to Charles Carroll, Sr., July 23, 1776 in Smith, Paul H., et. al., eds. Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789. Vol. 4, May 16-Aug. 15, 1776. (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1979), p. 523.

15. “From George Washington to General William Howe, 6 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, p. 410.]

16. “Extract of a Letter from Sir William Howe to Lord George Germain, Phila, October 22, 1777" No. 711, Dorchester, Guy Carleton, and Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. British Headquarters (Sir Guy Carleton) Papers, 1747 (1777)-1783. Washington, D.C: Recordac Corp., 1957; Lord George Germain to Sir William Howe, Whitehall, February 4, 1778. No. 919, Dorchester, Guy Carleton, and Great Britain. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. British Headquarters (Sir Guy Carleton) Papers, 1747 (1777)-1783. Washington, D.C: Recordac Corp., 1957.

17. John André. “Particulars of the Mischianza Exhibited in America at the Departure of Gen. Howe.” Gentlemen’s Magazine. August 1778: 353-357; Scull, G. D., ed. “The Montresor Journals” Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1881. (New York: For the Society, 1882), p. 484, 493 & 494.

18. John Brooke. “Howe, Hon. William (1729-1814). History of Parliament Online.” The History of Parliament: British Political, Social & Local History. Last modified 2020. Accessed August 14, 2025.

19. Ibid, & “At the Court at St. James’s, the 21st of June, 1782, Present…” The London Gazette, June 18-22, 1782, accessed August 15, 2025.

20. Great Britain. War Office. 10th January, 1794. A List of the Officers of the Army and Marines, With an Index... 42 ed. (London: Printed by G.E. Eyre & W. Spottiswoode..., [1794]), p. 2.

21. “Obituary” The Morning Post (London, England) Thursday, July 14, 1814.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Troyer Steele. The Command of the Howe Brothers During the American Revolution. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1936).

Gruber, Ira D. The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. (New York: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va. [by] Atheneum, 1972).

Smith, David. William Howe and the American War of Independence. (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).