The Southern Strategy was a plan implemented by the British during the Revolutionary War to win the conflict by concentrating their forces in the southern states of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. Although the British proposed plans for a southern campaign as early as 1775, the strategy did not come to full fruition until France became America’s ally following the latter’s decisive win at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. France’s subsequent entry into the war in February 1778 forced the British to reevaluate the war in America. British Secretary of State for the American Department, Lord George Germain, responded by turning to the Southern Strategy. The strategy depended upon the assumption that many southerners remained loyal to the British. American loyalist support never matched Germain’s expectations, and harsh tactics used by the British on their southern campaign only further alienated southern loyalists. By 1781, the Southern Strategy failed to prevent British defeat in the war as the British were defeated at Yorktown.

Naval Strategy and the Southern Campaign

In the early years of the war, the British attempted to take Charleston. Major General Charles Lee defended Charleston from British forces led by General Henry Clinton and Commodore Peter Parker in June of 1776. Using fortification on Sullivan’s Island, the effectively stopped British ships from entering Charleston harbor. By denying their occupation of the major port, British interests shifted north. In what is considered by some the first major American victory of the revolution, the south remained largely free from the harassment of British troops until the British adopted the Southern Strategy.

In late 1778, Germain directed the British to begin their campaign in the small, sparsely populated, and heavily divided colony of Georgia. The Southern Strategy initially achieved success there with the British capture of Savannah, Georgia in December of 1778. A major port city, its position afforded the British an area to stage another attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina. Additionally, thousands of colonists in Georgia defected the British. After an unsuccessful siege by the Continental Navy and French forces to retake the city the following year, the British continued to expand their control of the southern colonies. George Washington predicted as much, writing after the failed siege, “Charles Town it is likely will feel the next stroke—This if it succeeds will leave the enemy in full possession of Georgia by obliging us to collect our forces for the defence of South Carolina, and will consequently open new sources for men and supplies and prepare the way for a further career.”1

Ultimately, the Continental Army was unable to defend Charleston. Perhaps the single-most devastating event for America in the entire war then occurred at Charleston, an American-held city since the start of the Revolution. Under the leadership of Henry Clinton, the British used land and naval forces to siege the city for six devastating weeks. After attempting various negotiations of surrender, American Major General Benjamin Lincoln was forced to surrender over five thousand troops and an ample amount of Continental supplies in May of 1780. Many taken prisoner would not survive. American Major General William Moultrie of South Carolina, who aided the American forces defending Charleston against the British, remarked on the desperate state of the American cause, stating that “at this time, there never was a country in greater confusion and consternation.”2 With the British occupying two major port cities, they turned their focus to the interior.

War in the Backcountry

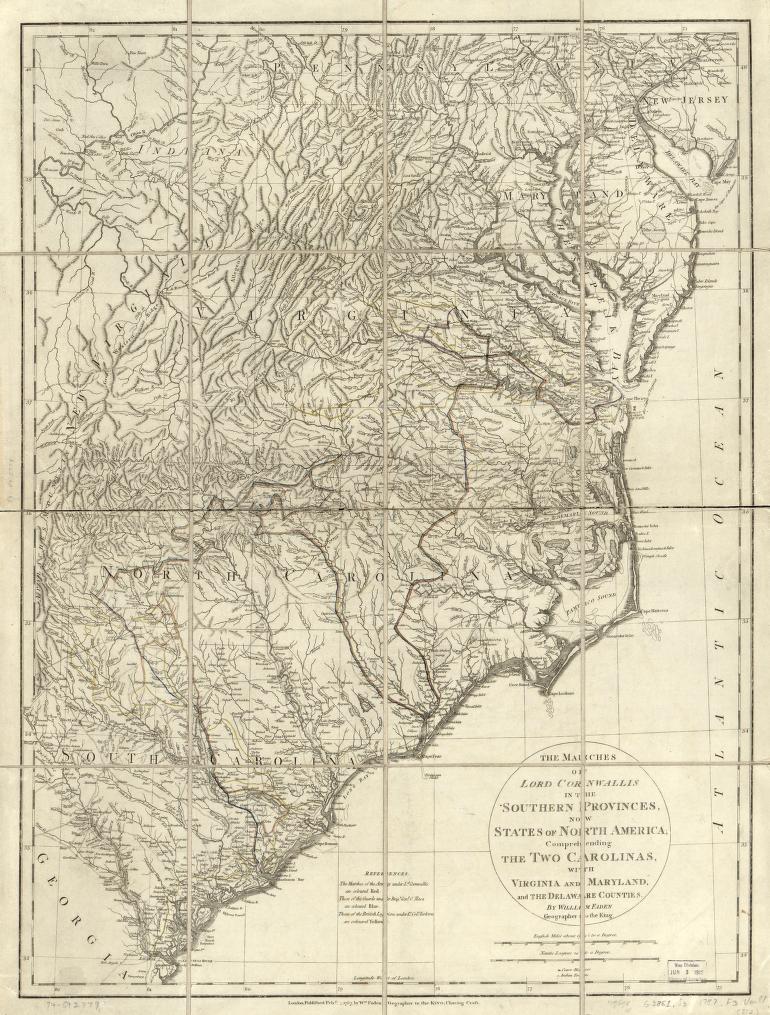

After Charleston’s fall, Clinton appointed Charles Cornwallis as the commander of the Southern Department before he returned to New York. Cornwallis began the task of fanning his troops into the southern backcountry, hoping to find loyalist support and quickly take the interior. Beyond the fall of Charleston, 1780 was demoralizing not only for the south, but for the entire American war effort.

As the British achieved initial success, their harsh practices in the South such as the brutality of officers like Colonel Banastre Tarleton began to incite feelings of resentment among southerners. Tarleton’s actions in allowing his cavalrymen to slaughter most of an American force at the Battle of Waxhaws in late May 1780 made him infamous for cruelty in the South. An American doctor present at Waxhaws recounted the massacre to be a “scene of indiscriminate carnage never surpassed by the ruthless atrocities of the most barbarous savages.”3 As a result, a fierce partisan war between an ever-growing number of American patriots and a shrinking number of loyalists ensued in the South from 1780 to 1782.

The Continental Army faced early struggles on the battlefield. American General Horatio Gates faced humiliating defeat against Cornwallis at the battle of Camden on August 16, 1780. In response, George Washington shifted strategy and leadership in the south. Washington appointed Nathanael Greene as the Commander of the Southern Army.4 Under his leadership and the local knowledge of militia leaders such as Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion, the Americans gained tactical traction against the British.

Patriot militiamen and even civilians attacked and gained control of loyalist strongholds in the backcountry. Guerilla bands led by backcountry patriots such as Thomas Sumter also began attacking supply trains of Cornwallis and his army, which challenged their strategy to expand their control of the south from the lowcountry. Suffering from supply chain issues, the effects of hot weather, and malaria, British forces began to lose their momentum.

American Victories

Southern patriot militiamen proved their growing strength over British forces at the decisive Battle of King’s Mountain in the North Carolina backcountry in October 1780. The Battle of King’s Mountain produced the first major American victory in the South since Savannah’s capture, and boosted the morale of southern patriots. Greene pursued a successful Fabian strategy against Cornwallis’s army. Greene divided his army, allowing Cornwallis to chase him through the Carolinas and into Virginia into early 1781.

Greene and one of his equally capable generals, Daniel Morgan, secured victory over the British at the Battle of Cowpens in January 1781. Remaining cautiously optimistic of their success, Greene wrote to Washington, “I am unhappy that the distressed situation of this Army will not admit of our improving the advantage we have gained. But I hope it has given the enemy a check that will prevent their advancing for some days.”5 Two months later, Greene secured another strategic victory even while technically losing at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Cornwallis lost a quarter of his army in the battle, leading him to abandon the backcountry of the Carolinas and move his army to Wilmington on the North Carolina coast to resupply and rest his troops. Cornwallis’s unsanctioned decision to then march his army to Yorktown, Virginia, effectively hastened the end of the British Southern Strategy.

Although British troops were still stationed at Charleston, Savannah, and Wilmington, Cornwallis’s retreat of the main British army in the South to Virginia allowed Greene’s army, which was still largely intact, to reclaim the Carolina backcountry. With Cornwallis’s evacuation, loyalists who remained either fled or pledged allegiance to the patriots for fear of their safety. Meanwhile, Cornwallis skirmished with American troops in Virginia under the Marquis de Lafayette during the summer of 1781.

In October, Cornwallis’s army fell under siege at Yorktown by American troops led by Washington and French troops led by the Comte de Rochambeau. The arrival of French ships on the York River pinned Cornwallis between the French Navy and the French and American troops, forcing him to surrender on October 19. With the surrender of the main British army operating in the South, the British Southern Strategy, as well as the major hostilities of the American Revolution, effectively ended.

Rachel McBrayer, George Washington University, Revised by Zoie Horecny, Ph.D., 15 August 2025

Notes:

1. “George Washington to Gouverneur Morris, 8 May 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution so far as it Related to the States of North and South-Carolina, and Georgia, (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 421.

3. William Dobein James, A Sketch of the Life of Brigadier General Francis Marion, (Marietta: Continental Book Co., 1948), 4.

4. “George Washington to Samuel Huntington, 22 October 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

5. “Major General Nathanael Greene to George Washington, 24 January 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Ferling, John E. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War for Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

James, William Dobein. A Sketch of the Life of Brigadier General Francis Marion. Marietta: Continental Book Co., 1948. Print.

Lumpkin, Henry. From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1981.

Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1913.

Moultrie, William. Memoirs of the American Revolution so far as it Related to the States of North and South-Carolina, and Georgia. New York: David Longworth, 1802. Print.

Pancake, John S. 1777: The Year of the Hangman. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1977.

—. This Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780-1782. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2003.