The “Indian Prophecy” is a legend told about George Washington’s miraculous survival at the Battle of the Monongahela, and a subsequent encounter he had with an Indigenous sachem. A variant version is sometimes known as “the Bulletproof President.”1 The tale is credited to Washington’s doctor and friend James Craik, and the fullest version was published by Washington’s step-grandson George Washington Parke Custis in the 1820s. Custis’ telling recalls that during a 1770 trip to what is now West Virginia, Craik and Washington encountered an Indian sachem (chief) who had fought against them during the Battle of the Monongahela on 9 July 1755. The sachem revealed that during the fight, he had ordered his men to kill Washington, but that all their shots had missed. He declared that “a power mightier far than we shielded [Washington] from harm.” He then predicted that Washington would “become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn, will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire.”2 The core of the story is one that has been in circulation since at least 1800. The historical truth of the story, however, is harder to discern. Like many stories about Washington, it likely contains a kernel of truth, but has been subject to embellishment and exaggeration over time.

Origins

Like many other Washington legends, a version of the story was first published by Mason Locke Weems in his original 1800 Washington biography. Weems’ version does not include the prophecy or the 1770 frame narrative, focusing instead on Washington’s miraculous survival at Monongahela despite orders to kill him. Weems gives no source other than claiming that a “famous Indian warrior” present at the battle “was often heard…to swear that ‘Washington was never born to be killed by a bullet.’”3 Weems’ original source may ultimately be Craik. Weems was married to a niece of James Craik’s wife Mariamne. An unpublished autobiography of Craik’s grandson Reverend James Craik in the collections of the Washington Presidential Library records that Weems was a close family friend who often stayed with the Craik family in Alexandria.4

The full version, with the attribution to Craik, was published by Custis as a stand-alone article entitled “The Indian Prophecy” in the United States Gazette in 1826. It was swiftly re-published in newspapers across the country, and later included in Custis’ posthumously published Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington.5 Custis claims that Craik told the story throughout the American Revolution, citing a specific example of him recounting the prophecy just before the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. On that occasion, Custis has Craik declare that "…their beloved Washington was the spirit protected being described by the savage, that the enemy could not kill him, and that while he lived the glorious cause of American Independence would never die".6 In 1827, Custis adapted the story into a popular play (also called The Indian Prophecy) which further cemented the legend in the American consciousness.

Historical Background

Craik was a close friend of Washington and his personal doctor, but more significantly for this story he was also at the Battle of the Monongahela as the regimental surgeon where the reported beginnings of divine protection occurred. During that fight, General Edward Braddock was mortally wounded, and nearly 70% of his men (including the vast majority of the officers) were killed or wounded. Washington, who was among the very few unharmed, led the retreat. Washington wrote to his mother shortly after the battle that bullets had pierced his clothing, and multiple horses had been shot from under him.7 Craik later told Washington’s early biographer, John Marshall, that he considered Washington’s escape from harm on the battlefield that day to be nothing short of miraculous: “‘I expected every moment,’ says an eye witness [Craik], ‘to see him fall.’ His duty and situation exposed him to every danger. Nothing but the superintending care of Providence could have saved him from the fate of all around him.’”8

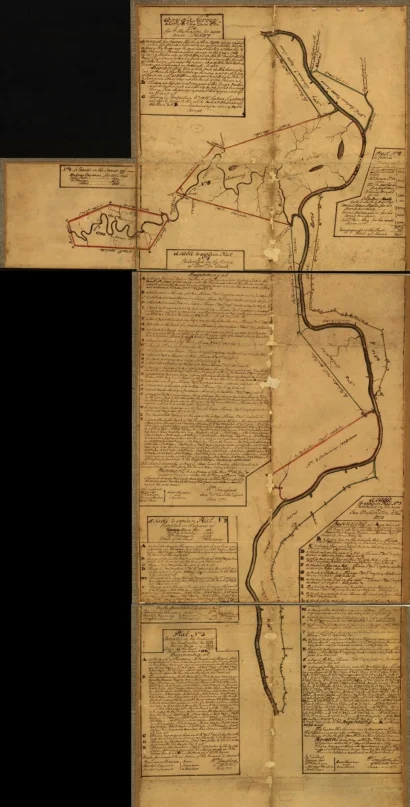

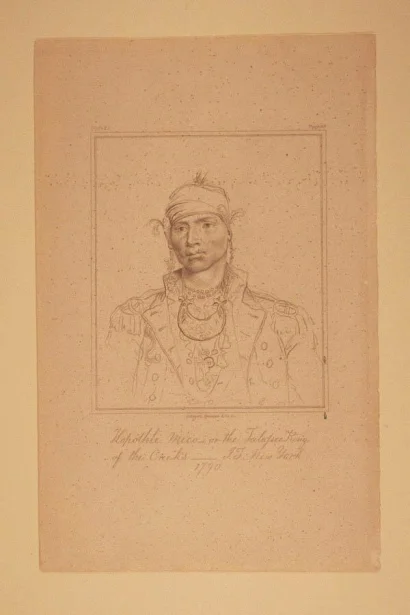

It is also well documented that Craik and Washington journeyed together to view Washington’s lands on the Ohio River in Fall of 1770. Washington kept two journals of that trip, and while he records several meetings with Indigenous people, he makes no mention of an encounter matching the later “Indian Prophecy” story. He did, however, encounter Indigenous people he had known during the early days of the Seven Years’ War, which is likely the origin of the tale later embellished and romanticized by Craik and Custis. In particular, on October 28th, Washington and Craik met with a hunting party led by the Seneca leader Guyasuta near modern Belleville, West Virginia. Washington had first met Guyasuta in December 1753, when he had accompanied Washington and the “Half King” Tanacharison to Fort Le Boeuf to meet with the French commandant.9 Washington recorded in his journal that “In the Person of Kiashuta [Guyasuta] I found an old acquaintance. He being one of the Indians that went with me to the French in 1753.”10

Guyasuta (also known as “the Hunter”) had initially been open to English advances, as evidenced by Washington’s own early experiences with him. However, he later joined with the French during the Seven Years’ War, and led hostilities against the British during Pontiac’s rebellion before re-opening friendly relations with the British in the later 1760s and 70s. Some authors have placed him among the French and Native attackers at Braddock’s defeat, which would make him an even better source of the legend; however, there is no solid evidence for this, and his name does not appear in either French or English contemporary sources.11

Mythmaking and the Nineteenth Century

The Indian Prophecy shares similarities with other tall tales about Washington, such as his legendary encounter with the cherry tree. It also fits in with a nineteenth century tradition of quasi-factual Indigenous “prophecies” and “curses” on a range of topics, playing on the “noble savage” trope. The story as told by Custis almost certainly did not play out in reality exactly as he (and perhaps Craik) described it. Divine Providence, however, is beyond the realm of the fact-check. Washington indeed escaped serious harm in the deadly Battle of the Monongahela, and this feat, combined with his later prominence, was seen as remarkable, if not miraculous, by Washington’s contemporaries – and perhaps even by Washington himself. The first president skirting death produced the context for the “Indian Prophecy,” which developed over several decades, building on verifiable facts along familiar patterns of mythmaking.

Alexandra L. Montgomery, PhD, Director for the Center of Digital History at George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon

Notes:

1. See for example David Barton, The Bulletproof George Washington (WallBuilder Press, 2002).

2. George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (Derby and Jackson, 1860), 304.

3. Mason Locke Weems, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits, of General George Washington (1800), 5. While not including an actual prophecy, Weems does suggest that with the benefit of hindsight, it looked “a good deal like” a prophecy. Weem’s version was later cribbed wholesale by Henry Trumbull in his long-running and oft-reworked History of the Discovery of America, which provided another avenue of dissemination to the general public: James Steward [Henry Trumbull], History of the Discovery of America (Grant and Wells: 1802), 92.

4. James Craik, “Autobiography of Rev. James Craik,” n.d., no. 157, box 87, Historic Manuscript Collection, George Washington Presidential Library.

5. George Washington Parke Custis, “The Indian Prophecy,” The United States Gazette, 2 May 1826.

6. Custis, Recollections, 222-223.

7. “George Washington to Mary Ball Washington, 18 July 1755,” Founders Online, National Archives.

8. John Marshall, vol 2, 18-29, 1804. The text clarifies that the eyewitness was Craik.

9. “Journey to the French Commandant: Narrative,” Founders Online, National Archives.

10. “Remarks & Occurrs. in October [1770],” Founders Online, National Archives. Washington met with Guyasuta again on November 6th on his return trip, where they discussed the “Subject of Land.”

11. For a modern author claiming that Guyasuta was present at Monongahela, see Brady J Crytzer, Guyasuta and the Fall of Indian America (Westholme, 2013); for the counter claim, see David Preston, Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2015), 6; see also Ibid., 363 n6 for Preston’s discussion of the sources of the “Indian Prophecy” legend.

Bibliography:

Preston, David. Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Steward, James [Henry Trumbull]. History of the Discovery of America. Grant and Wells: 1802.

Weems, Mason Locke. A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits, of General George Washington. 1800.