The Battle of Camden was a major engagement in South Carolina during the American Revolutionary War. Fought on August 16, 1780, between an American army commanded by General Horatio Gates and a British force led by General Lord Charles Cornwallis, the engagement resulted in a British victory. In the aftermath, Congress removed Gates as the commander of the Southern Army, and General George Washington replaced him with General Nathanael Greene.

The War Turns South

The first several years of the Revolutionary War were primarily concentrated in the Northern states, but British leadership shifted its approach beginning in late 1778. The war in the North was at a stalemate and Britain hoped to tap into the supposedly large Loyalist population in the South to retake the region. Called the “Southern Strategy,” this approach began successfully in December 1778 with the capture of Savannah and the subsequent restoration of Georgia’s provincial government.

The Southern Strategy saw further success in the spring of 1780 when a force under General Henry Clinton placed Charleston—the largest city in the South—under siege. The American army in the city, commanded by General Benjamin Lincoln, surrendered after several months of resistance. The British then established posts across South Carolina, including at Camden, about 125 miles to the northwest of Charleston. Camden was the linchpin of the British occupation, situated at a crossroads, allowing Britain to assert control inland. A few weeks after capturing Charleston, Clinton returned to New York, leaving Cornwallis in command.

Following Lincoln’s surrender, Congress appointed General Horatio Gates as the head of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. Gates brought a record of battlefield success, famously capturing an entire British army at Saratoga in 1777. Congress hoped Gates would replicate his accomplishments in the North. Gates went south and assumed command at Buffalo Ford, located along the Deep River in North Carolina. These troops, commanded by General Johann de Kalb, had been sent by General George Washington to reinforce Lincoln, but halted on learning of Charleston’s surrender.

American Forces March to Camden

Gates found the army in very poor condition, and lacking effective supply lines. He determined to move immediately, remarking “We may then as well move forward & starve, as starve lying here.”1 He chose to march directly to Camden, hoping to absorb a force of North Carolina militia along the way. This decision went against the advice of some of his officers who preferred a more circuitous route they believed would bring them through areas more friendly to the Revolution and would have abundant provisions. Gates gathered reinforcements along his march, and his army ultimately comprised approximately 3,000 men. Although most of his soldiers were North Carolina and Virginia militia, he also had Maryland and Delaware Continentals.

Due to his dependence on militia, Gates decided against a direct attack on Camden. He feared the militia would not fare well in an open battle. Instead, he planned to occupy a defensive position along Sanders Creek, a few miles north of Camden. From there, American forces could harass Camden’s supply lines. Gates thought this strategy would force the commander of the Camden garrison, Lieutenant Colonel Lord Francis Rawdon, to either abandon the community or launch a risky frontal attack against Gates’ defenses. Major Thomas Pinckney, one of Gates’ aides-de-camp, described the position along Sanders Creek as a “thick swamp on the right, a deep Creek in front & thick low ground also on the left,” making it a good spot to receive an attack.2

As Gates advanced, Rawdon withdrew from his defenses outside Camden and called reinforcements to bolster his garrison. News of Gates’ approach prompted Cornwallis to leave Charleston for Camden, where he arrived on August 13. Cornwallis decided to take the offensive, ordering his army to march on the night of August 15. In an extraordinary coincidence, at about the same time on the same night, Gates ordered his army to move to Sanders Creek. Neither commander knew the other was advancing. The two armies collided about six miles north of Camden, preventing Gates from reaching his planned defensive position. Both sides engaged in indecisive skirmishing before reorganizing to prepare for a larger battle the next day on August 16.

The Battle of Camden

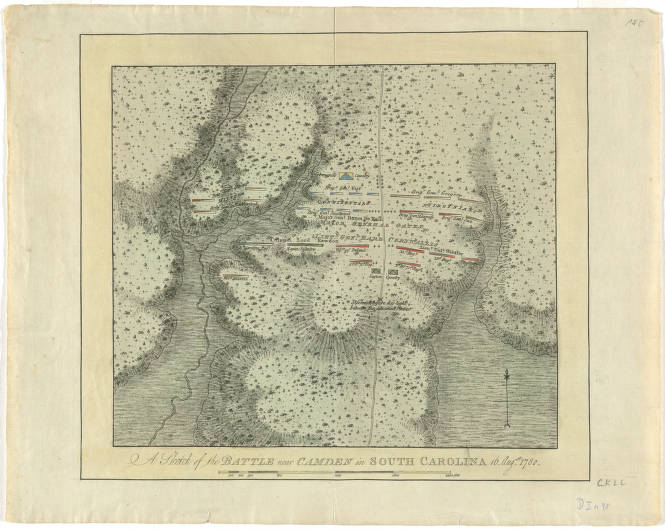

Gates began deploying his troops, placing the Virginia militia on his left, the North Carolina militia in the center, and the 2nd Maryland Brigade on his right. Gates remained in the rear with the 1st Maryland Brigade, which was held in reserve. Cornwallis’ army, although somewhat smaller than Gates’ with around 2,300 men, contained better troops. He placed two experienced British regiments on his right, directly across the battlefield from Gates’ inexperienced militia.

As the two armies faced each other on the morning of the 16th, Colonel Otho Holland Williams of Maryland recommended the Virginia militia move forward, believing he saw the British right maneuvering. Gates agreed and gave the order. Gates also sent Pinckney to order Kalb, who commanded the 2nd Maryland Brigade on the right, to advance in support of the Virginians’ movement. At the same time, Cornwallis ordered his army to attack. The British right unleashed a volley, huzzahed, and advanced with their bayonets, prompting the Virginia militia to turn and run. Many of the militia threw their loaded muskets on the ground, not having fired a shot. The panic spread to the North Carolina militia, most of whom also fled. With that, Gates’ left flank collapsed, and the majority of his army dissolved.

Gates attempted to rally the militia, believing the army’s position was untenable unless they could be reformed. Gates made several efforts to halt their flight, but later reported to Congress he was unsuccessful because they kept running “like a Torrent and bore all before them.”3 Edward Stevens, commander of the Virginia militia, similarly told Governor Thomas Jefferson “it was out of the power of Man to rally them.”4 British cavalry harassed the militia as they ran away, spreading terror and making Gates’ attempts to reform them much more difficult.

With the militia on the run, the 1st and 2nd Maryland brigades under Kalb were left to face the British and Loyalist Provincial forces alone. The Continentals held out for a while, inflicting substantial casualties on the British in the process, but they were eventually overwhelmed. Kalb was mortally wounded in the fighting while the Marylanders and Delawareans fled into the swamps and woods to escape capture or death.

In just forty-five minutes, Cornwallis had inflicted a major defeat on the American war effort in the South. Cornwallis claimed Gates suffered eight to nine hundred killed or wounded and one thousand captured. Cornwallis followed this victory by ordering his subordinate, Banastre Tarleton, to pursue Thomas Sumter’s partisan forces. On August 18, Tarleton surprised and defeated Sumter at Fishing Creek, some thirty-five miles northwest of Camden.

Aftermath of the Battle of Camden

After the defeat, Gates went to Charlotte. Upon learning that Charlotte had few supplies, Gates pressed on to Hillsborough, where the North Carolina legislature was meeting, believing it offered the best place to rebuild the army. His decision to ride to Hillsborough, around 200 miles from Camden, led to substantial criticism from those who thought he had abandoned his army.

Despite his victory, Cornwallis did not benefit from Camden as much as he had hoped. He found it difficult to pacify South Carolina, with strong resistance continuing from partisan leaders, such as Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion. The defeat of Loyalists at the Battle of Kings Mountain in early October was a particularly large blow to the British war effort in the South. Cornwallis’ army also suffered from persistent sickness that disrupted his operations.

On the American side, Gates rebuilt the Southern Army in North Carolina. He did not, however, survive the criticism that followed his defeat at Camden. Congress recalled Gates and placed General Nathanael Greene in charge of the Southern Department, who arrived in Charlotte to take command in early December.5 Under Greene, the Southern Army would see greater success and ultimately restore South Carolina to the United States.

Kieran J. O’Keefe, Ph.D., Lyon College

Washington Library Fellowship Class 2024-2025

Notes:

1. Thomas Pinckney to William Dobein James, July 31, 1822, The Papers of the Revolutionary Era Pinckney Statesmen Digital Edition, ed. Constance B. Schulz, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2016.

2. Robert Scott Davis Jr., “Thomas Pinckney and the Last Campaign of Horatio Gates,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 86, no. 2 (Apr. 1985): 86.

3. Horatio Gates to Congress, August 20, 1780, Transcripts of Letters from Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, 1775-81, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives.

4. “To Thomas Jefferson from Edward Stevens, 20 August 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

5. “George Washington to Samuel Huntington, 22 October 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Carpenter, Stanley D. Southern Gambit: Cornwallis and the British March to Yorktown. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

Maas, John R. Horatio Gates and the Battle of Camden: “That Unhappy Affair,” August 16, 1780. Camden, SC: Kershaw County Historical Society, 2001.

Orrison, Robert and Mark Wilcox. All That Can Be Expected: The Battle of Camden and the British High Tide in the South, August 16, 1780. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2023.