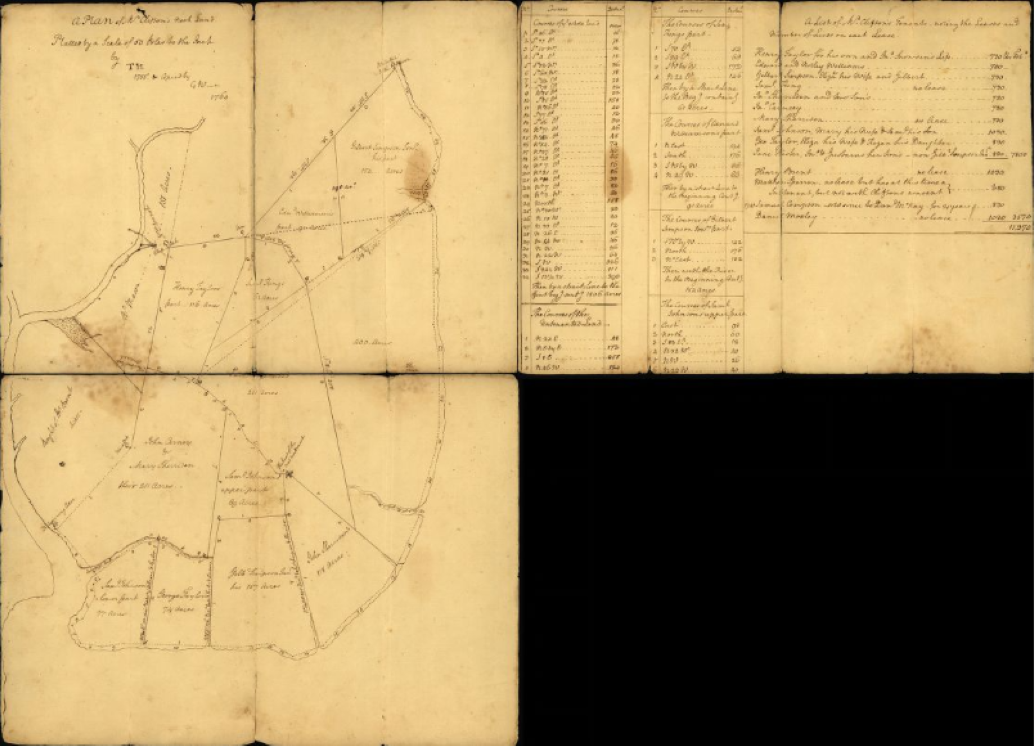

George Washington purchased the tracts of land that would become River Farm from William Clifton and George Brent in 1760. River Farm was situated between two sides of the Potomac River and was separated from Mount Vernon and Mansion House Farm by Little Hunting Creek. Initially referred to as “Riverside Quarter” or “River Quarter,” the property became known as River Farm as Washington developed his properties known together as the Five Farms in the following years. By 1796, River Farm was Washington’s largest farm at 1207 acres.1 The property was an established farm with deep-water access, views of the Potomac River, and tillable land suitable for agriculture. At the time of his death in 1799, the Washingtons enslaved fifty-seven people at River Farm.2

Washington’s Reorganization of River Farm

As Washington reorganized how he managed his farms, he explored agricultural advances in new husbandry. In 1766, Washington oversaw improvements at River Farm. He directed the clearing of three large fields and fencing throughout the property to support five orchards, a dozen buildings, and a landing along the river. One of the buildings was a larger, two gable-ended house with domestic outbuildings near the river. Other buildings included smaller chimneyed dwellings houses such as a home for an overseer and several houses for enslaved people. In 1795, Washington continued improvements to River Farm with the addition of sheds and a brick barn.3

River Plantation was on a 7-year crop rotation with lots reserved for pasture-ground and clover. In 1789, Washington directed the future cultivation of grains such as barley and oats, corn, limited tobacco, potatoes, carrots, and buck-wheat using this rotation.4 Crops such as beans and pumpkins were also periodically grown there.5 Often crops grown at River Farm such as wheat varieties were further processed by enslaved laborers at Douge Run Farm. Washington directed experiments on fertilizer at River Farm, such as taking mud from the Potomac River as a substitute for manure.6

River Farm was cooperatively managed alongside his other properties by Washington’s various farm managers, such as Lund Washington, who was farm manager from 1764 to 1785. Alexander Cleveland, a former overseer at Muddy Hole Farm, returned to work for Washington as the overseer of River Farm from 1773 to 1775. Later overseers of River Farm include Anthony Whitting from 1790 to 1793.

Slavery at River Farm

In some instances, those enslaved at Douge Run Farm and River Farm were under the direction of an enslaved overseer who reported to a farm manager or superintendent. In 1786, Davy was the enslaved overseer for River Farm, and was living there with his wife Molly. He later became an enslaved overseer at Muddy Hole Farm.7

In 1799, there were fifty-seven enslaved people living on River Farm, including twenty-seven enslaved by Washington and another thirty people enslaved by Martha Washington. Of the thirty-eight adults enslaved there, nine had spouses living elsewhere, such as Judy whose husband Gabriel was enslaved at Muddy Hole farm. Five couples lived together at River Farm. Nineteen of those living there were under the age of eleven, so possibly being raised by other relatives at River Farm.8

Most of those enslaved at River Farm engaged in agricultural labor such as cultivation or tending to livestock. However, Sambo was a carpenter, Cyrus was as postilion, and Moll was a cook.9

River Farm at the End of Washington’s Life

In 1796, Washington began efforts to lease land and those enslaved at River, Union, and Douge Run Farms under strict terms.10 Tobias Lear had interest in leasing River Farm as he had property nearby, but ultimately Washington retained the ownership and operations of his properties until his death.11 In in his final days, Washington conceived various plans concerning his properties, including River Farm, detailing new crop rotations and proposed improvements.12 After his death, James Anderson, continued as the farm manager, including the supervision of River Farm, until Martha Washington’s death in 1802.

Washington bequeathed much of the land that comprised River Farm to his extended family. Tobias Lear, the widow of Washington’s niece, Frances Bassett Washington Lear, lived in northeast corner of River Farm with her two children George Fayette Washington and Lawrence (Charles) Augustine Washington. Washington desired they remained on the property.13 Those enslaved by Washington at River Farm were manumitted by Martha in accordance to his will in 1801. Those considered “dower slaves,” or enslaved through the Custis estate, at River Farm were inherited by members of the Custis family.

Zoie Horecny, Ph.D.

Notes:

1. “Advertisement, 1 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. "Washington’s Slave List, June 1799," Founders Online, National Archives.

3. “From George Washington to William Pearce, 23 December 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives; “From George Washington to William Pearce, 21 December 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives; “From George Washington to William Pearce, 10 May 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives.

4. “From George Washington to John Fairfax, 1 January 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives.

5. “[Diary entry: 13 November 1787],” Founders Online, National Archives.

6. “From George Washington to George Gilpin, 29 October 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives

7. [Diary entry: 18 February 1786], Founders Online, National Archives.

8. "Washington’s Slave List, June 1799," Founders Online, National Archives.

9. "Washington’s Slave List, June 1799," Founders Online, National Archives.

10. “Lease Terms, 1 February 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives.

11. “From George Washington to Tobias Lear, 11 September 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives.

12. “Enclosure: Washington’s Plans for His River, Union, and Muddy Hole Farms, 10 December 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives.

13. “George Washington’s Last Will and Testament, 9 July 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Dalzell, Robert, Jr. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ragsdale, Bruce A., Washington at the Plow: The Founding Farmer and the Question of Slavery. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021.

Schoelwer, Susan P., ed. Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington's Mount Vernon. Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies Association, 2016.

Thompson, Mary V. “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret”: George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2019.