George Washington, like many prosperous planters in the colonies of Virginia and Maryland, depended on the labor of indentured European servants in addition to the enslaved labor of those of African and Indigenous descent. Indentured servitude was an institution where poorer men and women exchanged the cost of their Atlantic passage and any accrued expenses of room, board, and clothing for years of labor. Among the population of “indentured servants” were convicted felons, whose sentences to be hanged were commuted for their transportation to the American colonies and then sale of their labor for either a seven- or fourteen-year terms. Only after hostilities broke out in 1775 did Britain stop shipping its convicts to the American colonies, and in 1786 British, Scots, and Irish felons began to be taken to Botany Bay and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Other indentured servants included military and political prisoners and, almost exclusively in the early to mid-seventeenth century, kidnap victims. Not until the end of the seventeenth century did the numbers of enslaved persons in Virginia outnumber those of indentured servants, and not until the early nineteenth century did indentured servants from the British Isles and Germany cease immigrating to the United States. George Washington’s personal history, his occupation as a planter, and his role as a military commander each manifested the important place that indentured servants (and freed, former servants) played in his life.

George Washington and Indentured Servants in His Early Life

Before Washington developed Mount Vernon, he interacted with indentured servants. Washington’s maternal grandmother, Mary Johnson, may have been an indentured servant and grew up poor and illiterate (although we know little about her early years and the circumstances of her arrival in North America). She married Col. Joseph Ball in late 1707 or 1708. Furthermore, Washington’s first tutor was “a convict servant bought as a schoolmaster,” and also served as a sexton, schoolteacher, and gravedigger.1

George Washington had other connections with indentured servants in his early military career. As Commander of the Virginia Regiment, Washington lamented the “ruinous state of the frontiers and the vast extent of the land we have lost since this time last twelve-month,” as a challenge to British progress in the Seven Years’ War.2 In order to clear this land for military purposes, he wrote that he knew of “no other method than to enlist Servants, even Convicts not excepted.”3 He proposed this idea to the colonial governor of Virginia Robert Dinwiddie. He suggested to enlist servants for the task and that their “owners” should “be paid a reasonable allowance for them.” In doing so, Washington wrote Dinwiddie, “we could soon complete the Regiment” and thereby “preserve the Forts” and “defend[] the country.”4 Governor Dinwiddie then allowed Washington to “enlist Servants” (as long as Parliament was agreeable), providing the Master of such Servant shall be paid for the Time they have to serve in Proportion to the first Purchase.” With Dinwiddie’s orders in hand, Washington spread the word of the governor’s approval and managed to recruit dozens of more servants to assist in non-combat tasks related to his expedition west.5

Indentured Servants and the Initial Development of Mount Vernon

An enterprising and ambitious planter, Washington needed skilled craftsmen, “mechanics,” for work at Mount Vernon and his outlying properties as he developed his landholdings. He therefore bought painters, brickmakers, weavers, joiners, tailors, shoemakers, and other tradesmen to build, furnish, paint, and otherwise improve the buildings, grounds, and living conditions at Mount Vernon. A few indentured servants were identified simply as “servants,” and were possibly house servants. Others had no listed skills and were likely unskilled laborers.

On some occasions Washington bought servants’ indentures directly from ship captains or their agents. He negotiated the purchase of convict servants with Captain William McGachen (or “McGachin”) of (John) Stewart & (Duncan) Campbell, a London shipping syndicate.6 He bought other men from ships carrying indentured servants that came up the Potomac to sell them in Alexandria.7But Washington usually bought his servants indirectly, through the offices of his plantation managers (as opposed to the overseers of individual plantations) or agents acting on his behalf, such as the merchant Philip Marsteller, Stewart & Campbell’s Virginia representative, Thomas Hodge, the Baltimore merchant Tench Tilghman (Washington’s former aide de camp in the Continental Army), and Valentine Crawford (Washington’s western land agent).8 The servants’ indentures varied in price, according to their skill, age, gender, country of origin, and the economy of the period. Washington paid £12 each for the three-year indentures of a shoemaker and a joiner from Ireland; he paid £35 for a four-year indenture of a tailor from England; and he paid a little over £45 for the three-year indentures of John and Rachel Knowles, a married bricklayer and a spinner and house-servant respectively.9

Washington owned upwards of forty indentured servants between 1760 and 1786, according to his diaries, account books, and correspondence. His records show that at least nineteen were natives of England, eight from Ireland, three from what is now Germany, and two from Scotland. Eight servants had no identified nationality. These servants included seven transported convicts, three of whom were English, two from Scotland, and two with no listed nationality. Two of the servants purchased by Washington were to train enslaved laborers. In September of 1759, John Askew, a shipbuilder, was leased to instruct those enslaved at Mount Vernon in his trade.10 Washington, like other planters, bought the indentured servants (or hired mechanics) to train their own enslaved persons, thus enabling the plantation to become more self-sufficient and lessening the need to obtain skilled workers in the future.

Washington also believed indentured labor was a viable strategy to developing his western lands. Washington purchased eight indentured servants in 1774 and 1775 for the purpose of settling and improving his holdings on the Great Kanawha River, on Jacob’s Creek (which flows into the Youghiogheny River), and on “Washington’s Bottom,” the site of present-day Perryopolis, Pennsylvania. Four of the servants ran away, which was not uncommon for indentured laborers.

Indentured Servants and the Revolutionary War

Five indentured servants at Mount Vernon also ran away. The first to do so was a “very compleat House painter” by the name of John Winter, who ran away in 1760, taking paint and oil with him.11As the American Revolution began, more indentured servants sought escape from their contracts. Dunmore’s Proclamation included freedom for indentured servants as well as the enslaved in exchange for their service to the British. Some Americans feared that convicts and servants who enlisted for the patriot cause would desert to the British, and that “nothing less than Death will restrain the Practice [of deserting to the British side].”12 Washington and other American military officers feared the British would “augment” their forces considerably with convicts and servants. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee advised “the Congress and General to take such measures as will scare this suspected class of Men” from joining the British Army.13

A painter named Joseph Smith, who Washington had hired out to his brother-in-law and second cousin, Fielding Lewis, ran away from Lewis in May 1775. In August of that same year, he fled to join Lord Dunmore’s British forces in exchange for his freedom. Two other indentured servants, a bricklayer and a joiner, used the cover of night to take a sailboat (“yaul”) on the evening of April 19, 1775—the day of the Battle of Lexington and Concord—to escape down the Potomac. Only one of Washington’s fugitive indentured servants, the painter Joseph Smith (who also went by “Joseph Wilson” and who had previously absconded from Fielding Lewis), was ever recaptured. He was captured in December 1775, after being wounded at the Battle of Hampton on October 26-27, 1775.14

The need for men to serve in the Continental Army was even more acute, because of the large numbers of Americans (predominantly farmers and men of property) who were exempted. In a letter to Washington, Gabriel Jones, a prominent lawyer in the Shenandoah Valley, remarked that “Servants and Vagrants are what the majority [of the army] is composed of.”15This was an exaggeration, but about a fifth of the Maryland recruits were “young and penniless” itinerant laborers and tenant farmers and one-fifth of Essex County (Mass.) enlisted men had been indentured servants.16

George Washington and Indentured Servants in the Early Republic

Washington bought ten of his thirty-seven servants after independence, between the years 1784 and 1786. Among them was a carpenter, gardener, house joiner (i.e., a framer), a stonemason, and a shoemaker. These individuals were crucial in his plans to continue developing Mount Vernon and his outlying properties after the war. He purchased his last indentured servants in November 1786, a young German couple with their three-year-old daughter. She was a cheesemaker and the husband a ditcher.

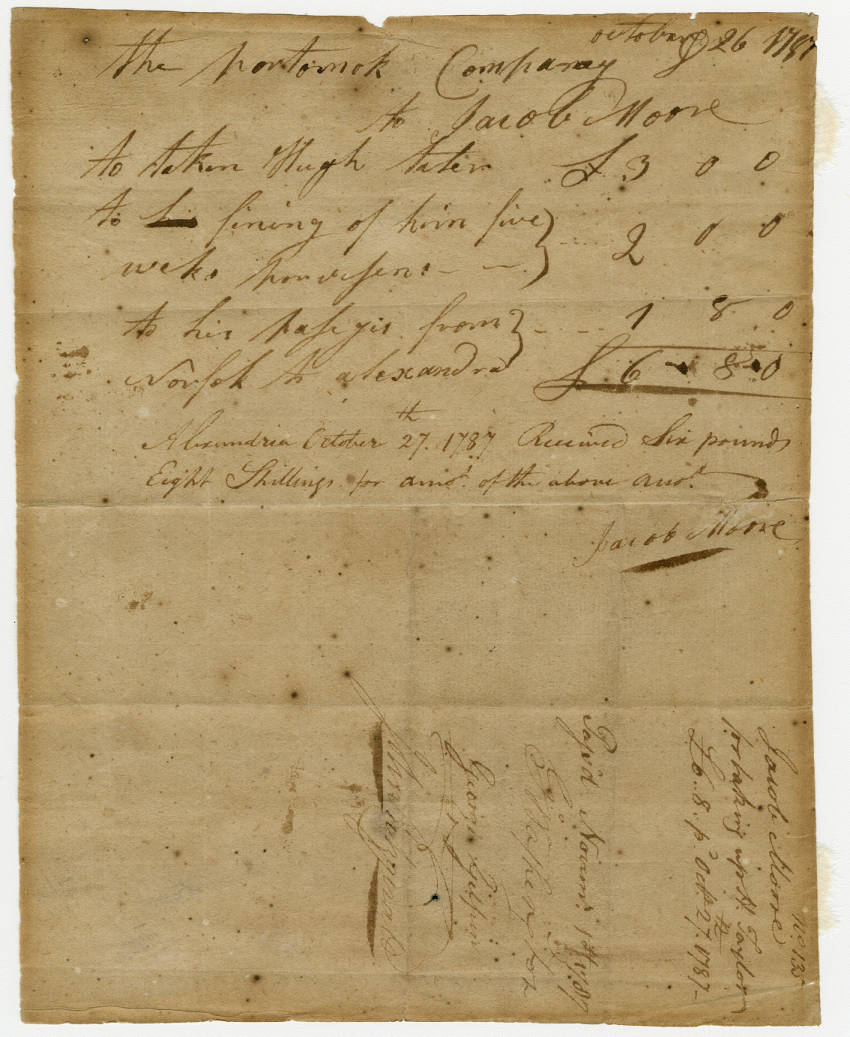

Washington also played an active part in the Potomack Company, in which he had shares. He ordered that the labor of sixty indentured servants be bought from either Philadelphia or Baltimore for constructing a series of locks to bypass Great Falls in order that vessels could go further up the Potomac River and trade with western towns. Washington described the “many Irish and German indentured servants and hired laborers” that labored “building locks and clearing the Potomac River and its tributaries for navigation.” They continued this work up until 1788, and the Potomack Company (which was to construct the locks) folded a few years later.17

By the late eighteenth century indentured servitude had been almost wholly replaced by enslaved labor. However, for Washington, fellow planters, iron foundry owners, and other wealthy Americans it was now typically used as means to procure skilled labor, such as painters, carpenters, and stonemasons, and for security years of labor for specialized tasks, such as large construction projects such as the Potomack Company’s canal project. But it was less and less important as a source of workers and gradually ceased altogether by the early 1830s.

Bartholomew Sparrow, PhD, The University of Texas at Austin

Notes:

1. Jonathan Boucher, Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 1738-1789 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1925), 49, cited in Elizabeth W. Marvick, “Family Imagery and Revolutionary Spirit: Washington’s Creative Leadership,” in George Washington and the Origins of the American Presidency, 77-91, eds. M. J. Rozell, W. D. Pederson, and F. J. Williams (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000), 85; also see Worthington Chauncey Ford, Washington as an Employer and Importer of Labor (Brooklyn, Privately Printed, 1889), 12.

2. “George Washington to John Robinson, 9 November 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives.

3. “George Washington to John Robinson, 9 November 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives.

4. “George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 4 August 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives. On 19 August 1756 Dinwiddie wrote Washington, agreeing to paying owners, “if You can enlist Servants agreeable to the Act of Parliamt” (“Robert Dinwiddie to George Washington, 19 August 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives) and on 13 September 1756, he wrote that although he knew “of no Act of ⟨Par⟩liamt on that head,” he had “Directions” from both the secretary of state and Lord Loudoun approving the enlisting of servants (“Robert Dinwiddie to George Washington, 13 September 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives.)

5. “George Washington to Adam Stephen, 6 September 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives; “George Washington to John Robinson, 9 November 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives. Hampering Washington’s and the Virginia Regiment’s recruitment efforts was the fact that the Virginia Assembly had not decided how much those who owned the indentures would be compensated for their lost value and had not (yet) provided any funds for such a purpose.

6. “George Washington To Richard Washington, Mount Vernon, 14 July 1761,” The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008. Colonial Series (7 July 1748–15 June 1775), Volume 7 (1 January 1761–15 June 1767); “George Washington to Robert Cary & Company, 4 October 1763,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 6 June 1764,” Founders Online, National Archives.

7. “[Diary entry: 4 June 1786],” Founders Online, National Archives; John P. Riley, Dec. 8, 1992. MVLA ("indentured servants—Mount Vernon (Va.: Estate).Vertical file.

8. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

9. “Memorandum List of Tithables, July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

10. “Indenture with John Askew, 1 September 1759,” Founders Online, National Archives.

11. “Cash Accounts, July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives. There is no record of when Washington bought or acquired John Winter.

12. “Cash Accounts, July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

13. “Council of War to George Washington, 9 May 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives.

14. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; also see “Lund Washington to George Washington, 3 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

15. “Gabriel Jones to George Washington, 6 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives.

16. Charles Patrick Neimeyer, America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army (New York: NYU Press, 1996), 18-19

17. “[Diary entry: 7 August 1797],” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Boucher, Jonathan. Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 1738-1789. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1925.

Dalzell, Robert F. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell. George Washington’s Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ford, Worthington Chauncey. Washington as an Employer and Importer of Labor. Brooklyn, Privately Printed, 1889, 12.

Neimeyer, Charles Patrick. America Goes to War: A Social History of the Continental Army (New York: NYU Press, 1996).

Suranyi, Anna. Indentured Servitude: Unfree Labor and Citizenship in the British Colonies. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021.

Thompson, Mary V. “The Only Subject of Regret:” George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon. University of Virginia Press, 2019.

Appendix of Indentured Servants Known by Name Purchased by George Washington

The appendix below represents indentured servants known by name, the decade(s) in which their indenture was active, and a brief description of their labor. In addition to enslaved labor, more than 300 hired and indentured servants worked at Mount Vernon throughout Washington’s ownership of the property. At least thirty of these laborers at Mount Vernon were indentured. Washington also indentured at least a dozen people to travel to and work his western lands, but their indentures were likely sold by to others. As a founding investor of the Potomac Company, he oversaw the purchase of indentured laborers to work on the project.

Andrew Judge (1772-1776, continued to work for Washington until 1780)18

An English tailor, Judge was originally signed with Alexander Coldclough before Washington purchased his indenture in 1772. He is believed to be the father of Ona Judge.

Anna Overdonck (1786-1788)19

Anna Overdonck was the infant daughter of Daniel and Margaret Overdonck, indentured servants from Germany. Her family was indentured by Washington from 1786 to 1788.

Catherine Boyd (1767-ca. late 1760s or early 1770s)20

Catherine Boyd was an indentured domestic servant, and Washington purchased her indenture from the estate of Captain George Johntson after his death. The duration of her indenture with Washington is unknown, but was likely between two to seven years.

Caven Bowe (Cavan Boa) (1786-1789)21

Caven Bowe was an indentured Irish tailor, and Washington purchased him when he arrived to the United States aboard the Ann in 1786. After his indenture, he owned a shop in Alexandria Virginia.

Charles Bush (1775-1780)22

Charles Bush’s indenture was purchased by Valentine Crawford for Washington in 1774. In 1775, he arrived aboard the ship Elizabeth. He was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River as a laborer. Bush was from Surry, and was eighteen years old when he arrived to North America. It is unclear, but it is unlikely that he completed his full indenture with Washington. Often, an agent for Washington would sell indentured servants to others further west.

Charles Stephens (1775-1780)23

Charles Stephens’ indenture was purchased by Valentine Crawford for Washington in 1774. In 1775, he arrived aboard the ship Elizabeth. He was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was twenty-two years old, from Bristol, and designated as a laborer. It is unclear, but it is unlikely that he completed his full indenture with Washington. Often, an agent for Washington would sell indentured servants to others further west.

Cornelius McDermott Roe (1784-1786, continued to work for Washington until ca.1788)24

Cornelius McDermott Roe was an indentured Irish stonemason and bricklayer. Washington purchased his indenture after he arrived to Alexandria aboard the Angelica. He continued to work for Washington for a wage after his indenture. His brothers worked for Washington as ditchers. He later worked as a stonemason and bricklayer constructing the United States Capitol.

Daniel Overdonck (1786-1788)25

Daniel Overdonck was a German indentured ditcher. His labor was purchased alongside his wife Margaret and their infant daughter Anna. His family was indentured to Washington from 1786 to 1788.

Elizabeth McPherson (1773-ca. 1777)26

Elizabeth McPherson’s four-year indenture was purchased for Washington by Valentine Crawford in Baltimore. She accompanied Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. She was joined by her husband Thomas McPherson who was indentured for the same duration of time. They were both Scottish. It is possible that their indenture was later sold by Crawford further west.

Farrell Slattery (1784-1786)27

Farrell Slattery was an indentured Irish millwright. His indenture was two years.

Henry Young (1774-1776, ran away from 1776-1778, returned to work for Washington 1778-1781)28

Henry Young was an indentured stonemason and convict when he arrived to Virginia in 1774. Washington purchased his indenture, but he likely did not complete it by the time he ran away in 1776. Although he was taken aboard the British warship Roebuck in 1776, he returned to Washington in Harlem Heights, New York. He continued to work at Mount Vernon in 1778 as a wage earner through 1781.

Isaac Web (1774-late 1770s)29

Isaac Web was an indentured bricklayer and convict when he arrived to Virginia. Washington purchased the twenty-four-year-old, who was from Bristol, England in 1774.

James Low/Lou (1773-ca. 1776)30

James Low’s three year indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore. Low accompanied Valentine Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was a thirty-six-year-old, unmarried husbandman. It is possible that his indenture was sold by Crawford further west.

John Askew (1754-1759 indentured to Mercer, 1759-1760 indentured to Washington, continued to work for Washington until 1767)31

John Askew was an indentured joiner. Initially, he was indentured to George Mercer of Fairfax County in 1754, and completed his indenture to him in 1759. However, he indentured himself to Washington for one year beginning in 1759. Given the immediacy in which he indentured himself to Washington, it is possible he was hired out to Washington while indentured by Mercer. Afterwards, he continued to work for Washington for a wage until 1767, performing tasks such as overseeing enslaved carpenters and supervising work on a schooner. As an employee, he was often in debt to Washington.

John Bailey/Baley (ca. 1775-ran away 1775)32

John Bailey’s indenture was purchased sometime during or shortly before 1775, and he was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He ran away in 1775 to join the British, and it was around this same time that Washington was purchasing more indentured servants to send to the western lands. It appears that he was recovered by American forces some time before the spring of 1777, and then he was court martialed, tried, and was condemned to die. It is unclear if that punishment was carried out.

John Broad (ca. 1773-death in 1776)33

John Broad was an indentured joiner purchased by Washington. He arrived to Virginia as a convict, and the duration of his indenture was likely three to four years. However, he was injured on Christmas of 1775, slicing his leg while participating in celebratory festivities. This likely resulted in the infection that led to his death in February of 1776.

John Knight (1773-ca. 1776)34

John Knight’s indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore in 1773. Knight accompanied Valentine Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was Scottish, twenty-one, unmarried, and considered himself a bookkeeper. It is likely that he was the surgeon’s mate by the name of John Knight who was captured with William Crawford on the Sandusky campaign of 1782 while serving in the American Revolution. Unlike Crawford, he survived and married Crawford’s niece Polly Stephenson, living in Pennsylvania until his death in 1838.

John Knowles (1773-1777, continued to work for Washington periodically through 1790)35

John Knowles was an indentured bricklayer and laborer from 1773 to 1777. His wife Rachel Knowles was also indentured, and worked for Washington as a spinner and house servant during the same duration of time. He later worked for Washington for a wage from 1777 to 1784, and then again from 1786 to 1790.

John Smith (1774-ca.1777)36

John Smith’s indenture three-year indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore. He was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River, accompanying Valentine Crawford and other indentured servants there. He was a convict when he arrived to Virginia. It is possible that his indenture was later sold further west by an agent acting on Washington’s behalf.

John Winter (late 1750s-1760)37

John Winter was an indentured painter. He was a convict when he arrived to Virginia. In 1760, he ran away with stolen paint and supplies.

John Wood (1773-ca.1776)38

John Wood’s indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore. Wood accompanied Valentine Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was from Scotland and considered himself a weaver. His indenture was likely sold by Crawford further west.

Joseph Smith/Joseph Wilson (1775-ran away in 1775)39

Joseph Smith was English, indentured painter purchased by Valentine Crawford for Washington in 1774 while aboard the ship Elizabeth, and when he arrived in 1775 he went to work at Mount Vernon. His original indenture was for four years. Washington hired him out to his brother-in-law Fielding Lewis in Fredericksburg to complete painting projects, and from there he ran away the following year. Smith joined British forces after Dunmore’s Proclamation using the alias Joseph Wilson.

Margaret Overonck (1786-1788)40

Margaret Overonck was a German indentured cheesemaker, spinner, washer, and milker. Her husband was an indentured ditcher, Daniel Overonck. Their daughter Anna was an infant when they arrived to Mount Vernon. They were indentured by Washington from 1786 to 1788.

Matthew Baldridge (1785-1788)41

Matthew Baldridge was an indentured joiner from England who was highly sought after by Washington. Washington reached out to the British firm of Robinson, Sanderson, and Rumney requesting to purchase an indentured servant who was a reliable joiner and bricklayer. He left Mount Vernon after his indenture expired.

Michael Tracy (1768-ca.1760)42

Michael Tracy was an indentured bricklayer from Ireland. Washington purchased his indenture in 1768, but it appears sold his indenture by July of 1770. It is likely he sold it to Andrew Wales in Alexandria, who reported a missing indentured servant named Michael Tracy that year.

Peter Miller (1773-ca.1776)43

Peter Miller’s three-year indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore. Miller accompanied Valentine Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was from Ireland and twenty-one in 1773. His indenture was likely sold by Crawford further west.

Rachel Knowles (1773-1777, continued to work for Washington periodically through 1790)44

Rachel Knowles was the wife of John Knowles, who was an indentured bricklayer. She labored as an indentured house servant and spinner. After their indenture, her and her husband later worked for the Washington family for wages until 1790.

Thomas Branagan (1784-1787)45

Thomas Branagan was an indentured joiner from Ireland. Washington purchased his indenture after he arrived in Baltimore.

Thomas Doe (1775-1780)46

Thomas Doe’s five-year indenture was purchased by Valentine Crawford for Washington in 1774 from the ship Elizabeth. When he arrived in 1775 he was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River and was accompanied by Valentine Crawford. He worked as a groom. It is unclear, but it is unlikely that he completed his full indenture with Washington. Often, an agent for Washington would sell indentured servants to others further west.

Thomas Mahoney (1784-ca. 1786, continued to work for Washington until 1792)47

Thomas Mahoney was an Irish indentured house carpenter and joiner who began his indenture in 1784 after arriving to Alexandria. His indenture likely ended sometime around 1786, when it appears he began to work with Washington for a wage. He often advocated for a higher salary. He worked for Washington until 1792.

Thomas McPherson (1773-ca.1777)48

Thomas McPherson’s four-year indenture was purchased for Washington in Baltimore. He accompanied Valentine Crawford to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River. He was joined by his wife Elizabeth McPherson. They were both Scottish. It is possible that their indenture was later sold by Crawford further west.

Thomas Ryan (1780s, early 1790s)49

Thomas Ryan was an indentured Irish shoemaker. Washington purchased him when he arrived aboard the Anne.

Thomas Spear (1774-1778)50

Thomas Spear was an indentured joiner from England. Valentine Crawford purchased him for Washington in 1774, and he arrived on the ship Elizabeth in 1775. After being purchased, he began to work at Mount Vernon. He he ran away later that year with another indentured servant named William Webster, but he was back at Mount Vernon by February of 1776 completing his four-year indenture.

Thomas Wight (1774-1781)51

Thomas Wight arrived to Maryland in 1774 as a convict. His seven-year indenture was purchased for Washington. He was sent to work west on Washington’s land on the Kanawha River. It is unclear, but it is unlikely that he completed his full indenture with Washington. Often, an agent for Washington would sell indentured servants to others further west.

William Orre/Cunningham (1774-ca. late 1770s)52

William Orre was a Scottish convict purchased for Washington in early 1774. Orre was sent to Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River, but ran away in Pennsylvania shortly thereafter. It appears he was later recovered because Washington sold his indenture to Hugh Hamilton in August of the same year.

William Tracy/Trasey (1775-1789)53

William Tracy’s four-year indenture was purchased by Valentine Crawford for Washington in 1774 from the ship Elizabeth, and he arrived to Alexandria, Virginia in 1775. As a carpenter, he was sent to work on Washington’s lands on the Kanawha River and accompanied by Valentine Crawford. It is possible his indenture was later sold further west by one of Washington’s agents.

William Webster (1774-1781)54

William Webster was an indentured brickmaker from Scotland who arrived to North America as a convict. George Washington purchased his seven-year indenture in 1774. He ran away with another indentured servant named Thomas Spear in 1775, and they were recovered shortly thereafter.

Appendix compiled by the Center for Digital History with the research of Mary V. Thompson, Bartholomew Sparrow, and Zoie Horecny

Notes:

18. “Cash Accounts, December 1772,” Founders Online, National Archives.

19. “Philip Marsteller to George Washington, 27 November 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives.

20. “Cash Accounts, May 1767,” Founders Online, National Archives.

21. "4 June 1786," The Diaries of George Washington, National Archives, Founders Online; [See entry dated "10 June 1786," in George Washington Cash Memoranda, Dec. 1784-July 1786 (original manuscript, Library of Congress; bound photostat, A-55, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association), 29; Quoted in Michael T. Miller, Artisans and Merchants of Alexandria, Virginia, 1780-1820 (Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc., 1991), 1:37-8; Mollie Somerville, Washington Walked Here: Alexandria on the Potomac, Midway between Mount Vernon and The White House (Washington, DC: The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, 1970), 110.

22. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 12 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

23. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 12 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

24. “Cornelius McDermott and George Washington, "1 August 1786, Memorandum of Agreement." George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence. 1697-1799; "September [1785],” Founders Online, National Archives; “[Diary entry: 10 December 1787],” Founders Online, National Archives; “To George Washington from the Commissioners for the District of Columbia, 31 May 1796," Founders Online, National Archives; “To Thomas Jefferson from Cornelius McDermott Roe, [on or before 14 July 1802],” Founders Online, National Archives.

25. “Philip Marsteller to George Washington, 27 November 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives.

26.“Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

27. John P. Riley, Dec. 8, 1992. MVLA ("indentured servants--Mount Vernon (Va.: Estate). Vertical file; “George Washington to Tench Tilghman, 4 August 1784,” Founders Online, National Archives.

28. Mesick, Cohen & Waite, "Building Trades," Historic Structures Report (Mount Vernon Ladies' Association): 2-46; see also entries for "1 August 1774," "1 November 1774," "Henry Young Stone Mason a Servt. for Tools & Cloaths," Lund Washington Account Book, 11. See also "Dr….Henry Young Stone Mason…Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 77; "From George Washington to Lund Washington, 6 October 1776," Founders Online, National Archives.

29. General Ledger B, 1772–1793. Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers; “Cash Accounts, March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

30. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

31. “Indenture with John Askew, 1 September 1759,” Founders Online, National Archives; Mesick, Cohen & Waite, Architects, "Building Trades," Mount Vernon: Historic Structure Report, 3 volumes (unpublished report prepared for the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, February 1993), 2-28; The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 7, 418n.

32. “Major General Israel Putnam to George Washington, 10 May 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives; “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

33. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 10, 137 & 138n; Mesick, Cohen & Waite, “Building Trades,” Mount Vernon: Historic Structure Report (unpublished report, Mount Vernon Ladies' Association), 2-29.; "Lund Washington to George Washington, 17 January 1776," Founders Online, National Archives; "Lund Washington to George Washington, 25 January 1776," Founders Online, National Archives; "Lund Washington to George Washington, 22 February 1776," Founders Online, National Archives.

34. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; Boyd Crumrine. History of Washington County, Pennsylvania, with Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. Philadelphia, 1882.

35. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 10, ed. W.W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia), 137, 137n-138n; "John Knowles and George Washington, July 7, 1789, Articles of Agreement," George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence. 1697-1799; See entries for "7 January 1774," and "29 September 1774," and "Dr. John Knowles Bricklayer for Tools & Cloaths," Lund Washington Account Book (Mount Vernon: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association), 12; "John Knowles….Dr….Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 74; "John Knowles (Bricklayer)…Dr….Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 111; "Dr….John Knowles…Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 129.

36. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

37. “George Washington, Cash Accounts [July 3rd, 1759],” The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008. Colonial Series (7 July 1748–15 June 1775), Volume 6 (4 September 1758–26 December 1760); Maryland Gazette [Annapolis], 26 June 1760.

38. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

39. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 12 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “Fielding Lewis to George Washington, 23 April 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), December 1, 1775; “George Washington to Lund Washington, 20 August 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

40. “Philip Marsteller to George Washington, 27 November 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives.

41. Mesick, Cohen & Waite, "Building Trades," Mount Vernon: Historic Structure Report, Vol. 2 (unpublished report prepared for the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, February 1993), 2-29; The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 4, 136n; The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 7, 418n.

42. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 8, 220; Mesick, Cohen & Waite, "Building Trades," Mount Vernon: Historic Structure Report (Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association), 2-44; "July 1768," The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 2, eds. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia), 77 & 77n. See also The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 8, ed. W.W. Abbot (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia), 112, 112n5; Virginia Gazette, 26 July 1770.

43. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives

44. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Vol. 10, ed. W.W. Abbot (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia), 137, 137n-138n; "John Knowles and George Washington, July 7, 1789, Articles of Agreement," George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence. 1697-1799; See entries for "7 January 1774," and "29 September 1774," and "Dr. John Knowles Bricklayer for Tools & Cloaths," Lund Washington Account Book (Mount Vernon: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association), 12; "John Knowles….Dr….Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 74; "John Knowles (Bricklayer)…Dr….Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 111; "Dr….John Knowles…Cr.," Lund Washington Account Book, 129.

45. "Tench Tilghman to George Washington, 27 July 1784," The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition, ed. Theodore J. Crackel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008; "George Washington to George Augustine Washington, 8 July 1787," The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition.

46. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 12 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

47. Mesick, Cohen and Waite, "Building Trades," Mount Vernon: Historic Structure Report (unpublished report, Mount Vernon Ladies' Association), 2-37; "Thomas Mahony to George Washington, 3 April 1788," The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, Vol. 6, 194; "Tobias Lear to Thomas Mahony, 4 April 1788," The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, Vol. 6, 194n.

48. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

49. “[Diary entry: 4 June 1786],” Founders Online, National Archives.

50. George Washington, "Advertisement for Runaway Servants, 23 April 1775," The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 3, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office); “To George Washington from James Cleveland, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 10, 21 March 1774?–?15 June 1775, ed. W. W. Abbot and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, pp. 365–367.]

51. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

52. “Valentine Crawford to George Washington, 27 July 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.; “Cash Accounts, August 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives.

53. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 12 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

54. “James Cleveland to George Washington, 21 May 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives; “William McGachen to George Washington, 13 March 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives; George Washington, "Advertisement for Runaway Servants, 23 April 1775,” The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 3, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office).