The Ethiopian Regiment (1775-1776) was an all-Black military unit that the Royal Governor of Virginia, John Murray IV, Lord Dunmore, raised in 1775 in Tidewater Virginia to undermine Patriot resistance at the start of the Revolutionary War. The regiment was comprised nearly-entirely of runaway Black slaves who fled from Patriot owners to join Dunmore, who offered to free them in exchange for their military service in November 1775 (Dunmore’s Proclamation). Among those who joined the regiment was a man enslaved by George Washington named Harry Washington. The regiment fought in several important battles in the Revolutionary War such as Kemp’s Landing, Great Bridge, Norfolk, and Gwynn’s Island before most of its soldiers died from disease and the regiment disbanded in August 1776.

The Beginnings of the Regiment

As tensions between Patriots and British soldiers in New England boiled over into the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Lord Dunmore attempted to suppress similar Patriot agitation in Virginia. Overnight on April 21, 1775, Dunmore ordered Royal Marines to remove gunpowder from the magazine in the colony’s capital in Williamsburg. What became known as “The gunpowder incident” stoked intense anger among Virginia Patriots who confronted Dunmore at his home and threatened to take military action against him. In response, Dunmore threatened to “declare freedom to the slaves & reduce the City of Wmsburg to ashes.”1 The incident was Dunmore’s first public musing of arming slaves against Patriots. Dunmore continued to threaten arming Patriot slaves as he evacuated Williamsburg on June 8, 1775, and sailed south to Norfolk’s harbor.

As more British soldiers arrived in Hampton Roads to reinforce Dunmore that summer, enslaved people began running away to British sailors to help them pilot boats and harass Patriot homes. Virginia Patriots grew increasingly agitated about the cooperation between Black slaves and British officers, which eventually culminated in the first battle of the Revolutionary War in Virginia on October 25, 1775, in Hampton, Virginia. Notably, Patriots demanded that British officer Captain Matthew Squire return Joseph Harris, a runaway enslaved man helping him, to his owner. Squire refused and during the battle several more slaves ran away to join the British and fight back against Patriot slave owners. Meanwhile, several Patriots claimed that Dunmore and Squire were inciting a slave insurrection in town.

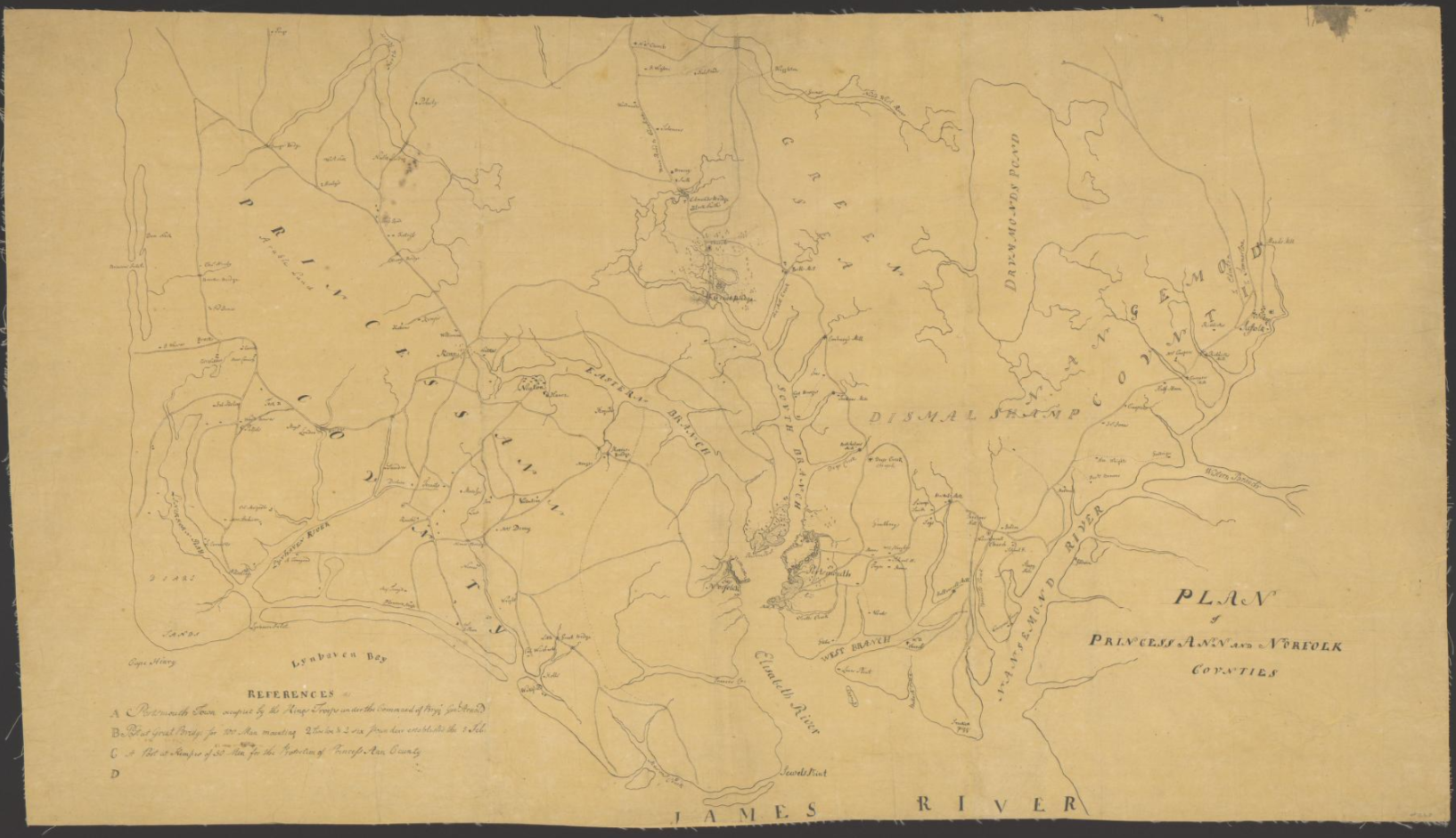

Following the Battle of Hampton, Dunmore and his British reinforcements began military forays outside Norfolk and in Princess Anne County to capture Patriot weapons caches and dislodge Patriot militia. Along the way more runaway slaves joined Dunmore’s forces. On November 7, 1775, Dunmore formally issued an emancipation edict, declaring “all indented servants, negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining his majesty’s troops.”2 Dunmore’s proclamation promised to free Patriot slaves if they fought for him against Patriot soldiers. Importantly, enslaved people belonging to Virginia Loyalists would not be freed.

Dozens of enslaved people fled to Dunmore in early November 1775 and at least a few of them took part in the next battle between Dunmore’s forces and Virginia Patriots. On November 15, 1775, fugitive slaves and British Regulars engaged the Princess Anne County militia at Kemp’s Landing several miles southeast of Norfolk, Virginia. Dunmore’s Black and white force routed Patriot militia, and during the battle slaves belonging to the Patriot commander, Colonel Joseph Hutchings, chased Hutchings down, hit him in the head with a sword, and took him prisoner. The Battle of Kemp’s Landing offered some of the first evidence of runaway enslaved people who became soldiers and who fought their former owners on the battlefield in the Revolutionary War.

The slave-soldier success at the Battle of Kemp’s Landing further encouraged Dunmore to receive and arm more runaway slaves for military service. Dunmore informed his superiors that “with our little corps, I think we have done wonders.”3 Subsequently, by the first week of December 1775, Dunmore officially mustered more Loyalist units, including an all-Black force “called Lord Dunmores [sic] Ethiopian Regiment.”4 While the regiment’s rank and file members consisted of free-Black and enslaved people, Dunmore appointed white officers to command the regiment’s companies and he retained overall control of the regiment’s actions.

Officially Mustered

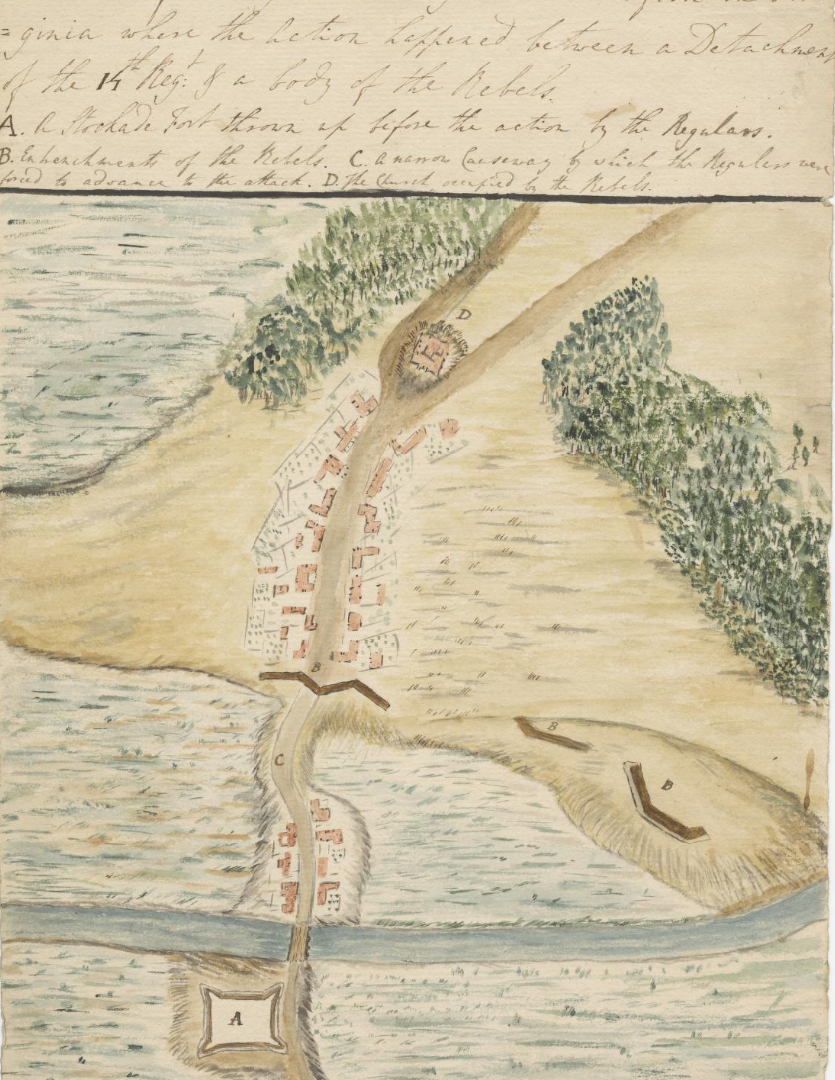

Once enslaved soldiers became an official military unit called the Ethiopian Regiment, they fought for their own freedom as they battled Patriot forces in Hampton Roads. Soldiers in the regiment wore white sashes with the words “liberty to slaves” inscribed on them. Within a week of their formal organization, soldiers in the Ethiopian Regiment fought in several skirmishes surrounding the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775, south of Norfolk. Dunmore had also ordered the regiment to be used in a pincer attack during the December 9 battle, which showed his trust in their fighting capabilities.5 Amid the British defeat at the battle, Patriots captured at least twenty-nine slaves who had joined the regiment or whom were thought to be trying to reach the regiment. Some of these prisoners were released, some were ordered transported to Antigua, others transported to lead mines in western Virginia for hard labor, and some were sentenced to death by hanging. It was clear that Patriots would not treat these men as regular soldiers in the British Army.

After their defeat at Great Bridge, soldiers in the Ethiopian Regiment fought in several skirmishes outside Portsmouth, Virginia, and were present for the Battle of Norfolk on New Year’s Day 1776. However, communicable diseases like typhus and smallpox began affecting soldiers’ fighting capabilities and in May 1776 the regiment evacuated with the rest of Dunmore’s forces to Gwynn’s Island in the Chesapeake Bay.

Hundreds of enslaved soldiers in the regiment continued suffering from smallpox and typhus while at Gwynn’s Island as they tried to defend the island from Patriot forces nearby. When Patriots finally landed on the island on July 9, 1776, most members of the Ethiopian Regiment had died or were too sick to fight. Patriot officers noted that they saw some “dying, and many calling out for help; and throughout the whole Island we found them strew’d about, many of them torn to pieces by wild beasts—great numbers of the bodies having never been buried.”6

Evacuation and Disbandment

Soldiers who were healthy enough to evacuate left Gwynn’s Island and continued to fight Patriot detachments further north in the Chesapeake Bay at St. George’s Island, Maryland, and along the Potomac River near Dumfries, Virginia. They also continued to take in more runaway slaves. It is during this part of the campaign that the regiment probably took in one of its most notable members: a man enslaved to George Washington named Harry. While George Washington’s cousin and Mount Vernon estate manager, Lund Washington, would later claim that Harry ran away in 1781 near the end of the war, Harry informed British officers that he ran away to the Ethiopian Regiment in summer 1776.

Despite continued raids and skirmishes in the northern Chesapeake, the Ethiopian Regiment was no longer an effective fighting force as the toll that smallpox and typhus had taken was too high. In August 1776 the regiment disbanded and evacuated the Chesapeake Bay with some members going to New York and some going to St. Augustine. Several members would continue to serve in successor all-Black military units in the British military and more than one hundred people affiliated with the Ethiopian Regiment survived the Revolutionary War and evacuated to Nova Scotia in 1783.

Influence and Legacy of the Ethiopian Regiment

Despite only moderate military success in Virginia in 1775 and 1776, soldiers in the Ethiopian Regiment influenced British and American military leaders in ways that affected policy later in the Revolutionary War and its aftermath. For example, George Washington wrote to Richard Henry Lee in late December 1775 that if Dunmore would not be “crushed before Spring, he will become the most formidable Enemy America has—his strength will Increase as a Snow ball by Rolling; and faster, if some expedient cannot be hit upon to convince the Slaves and Servants of the Impotency of His designs.”7 Washington also noted to John Hancock a week later at the end of 1775 that free Blacks in the Continental Army worried about “being discarded” and that they might “seek employ” with the British Army.8 Examples like the Ethiopian Regiment and the promise that Black military service would be rewarded in the British Army was a concern for the top general, and Washington consequently advocated for free Blacks to serve in the Continental Army.

Conversely, the Ethiopian Regiment served as a powerful example of the utility of enslaved military units within the British Army. In 1779 Sir Henry Clinton offered to free even more enslaved people in South Carolina with his Philipsburg Proclamation and the British military established several other all-Black military units such as the Carolina Black Corps and Black Pioneers. The success of Black Loyalist units like the Ethiopian Regiment also prompted the British Army to establish a permanent and professional enslaved fighting force in 1795 known as the West India Regiments. The West India Regiment would also become the largest enslaved fighting force in the history of the Atlantic world and would remain part of the British military until the twentieth century.

Justin Iverson, Ph.D.

Notes:

1. Deposition of Dr. William Pasteur, 1775, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 13, no. 1 (July 1905): 48, 49

2. Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), Williamsburg, November 23, 1775.

3. Dunmore to General Howe, November 30, 1775, in Force, American Archives 4th series vol 3:1713.

4. Dunmore to Dartmouth, December 6, 1775, NDAR 2: 1309-1311.

5. Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, December 13, 1775, CO 5/1353, fols 321-34.

6. Revolutionary War Journal of Captain Thomas Posey, July, 8-10 1776, Indiana Historical Society, 1:10.

7. “George Washington to Richard Henry Lee, 26 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

8. “George Washington to John Hancock, 31 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Egerton, Douglas. Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Frey, Sylvia, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Gilbert, Alan. Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Pybus, Cassandra. Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

Quarles, Benjamin. The Negro in the American Revolution, 50th anniversary edition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Taylor, Alan. The Internal Enemy: Slavery in Virginia, 1772-1832. New York: Norton, 2013.