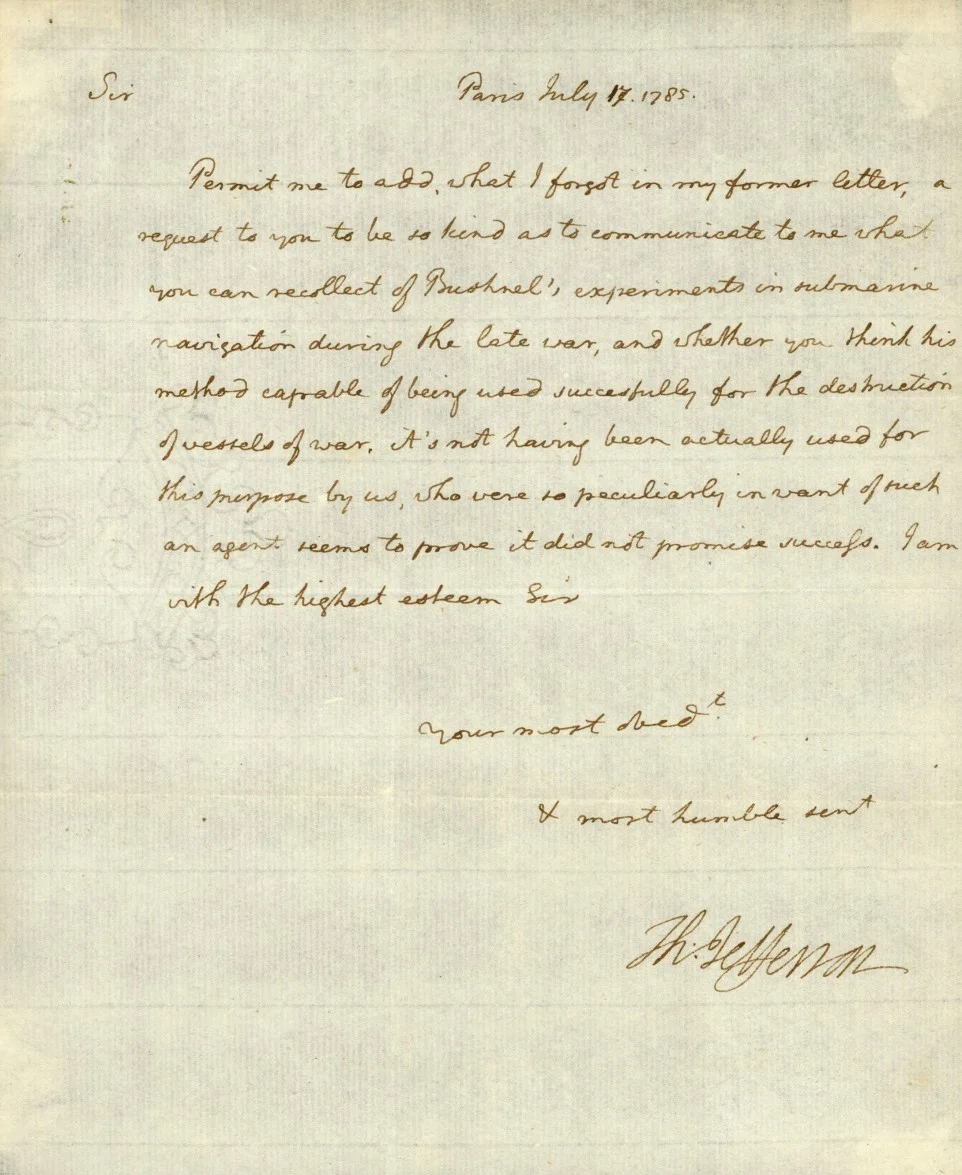

A brief but fascinating letter in Mount Vernon’s collection spotlights a little-known chapter of early American maritime history.

The letter is short—only 102 words. But its significance becomes apparent when one realizes that the sender is Thomas Jefferson, the recipient is George Washington, and the subject is submarine warfare. It reads:

Paris July 17, 1785

Sir,

Permit me to add, what I forgot in my former letter, a request to you to be so kind as to communicate to me what you can recollect of Bushnel’s experiments in submarine navigation during the late war, and whether you think his method capable of being used successfully for the destruction of vessels of war. It’s not having been actually used for this purpose by us, who were so peculiarly in want of such an agent, seems to prove it did not promise success. I am with the highest esteem Sir

Your most obedt & most humble servt

Th Jefferson

Let's back up.

Who is the “Bushnel” in Jefferson’s letter?

David Bushnell was an inventor and a soldier of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

Born in Connecticut in 1740, Bushnell used his inheritance to enroll in Yale College at the relatively old age of 31. While there, Bushnell conducted experiments with gunpowder. Convinced he could explode it underwater, he successfully detonated two ounces and later two pounds of gunpowder in this manner.

After refining these experiments, Bushnell focused on inventing a submarine to carry these mines underwater.

The Turtle

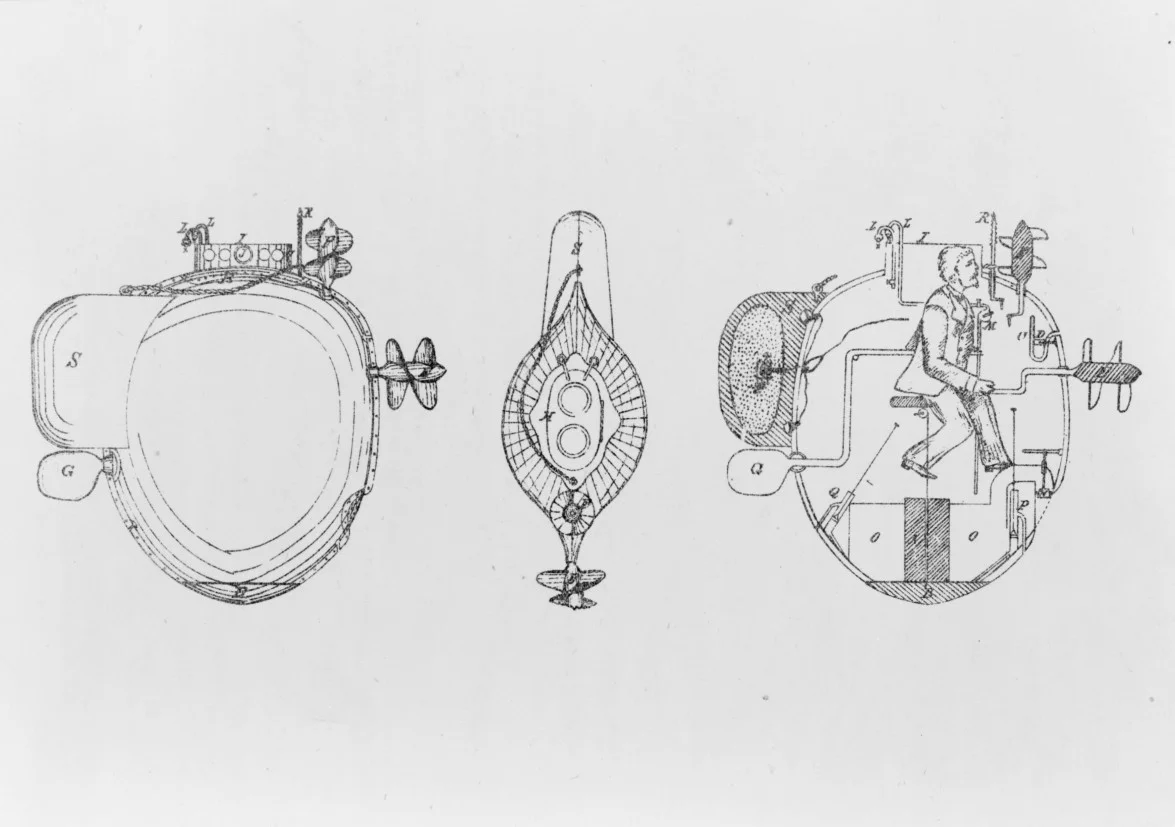

Bushnell’s subsequent invention, known as the Turtle, is considered the first American military submarine. As later described by Bushnell:

The external shape of the sub-marine vessel bore some resemblance to two upper tortoise shells of equal size, joined together; the place of entrance into the vessel being represented by the opening made by the swell of the shells, at the head of the animal.

Dedicated to the American cause, Bushnell was eager to test the Turtle in battle against a British vessel.

Attempt #1

After brief training, Sergeant Ezra Lee set out in the Turtle from Long Island at midnight on September 6, 1776, with the flagship HMS Eagle as his target.

Lee was able to sail underwater up to the ship’s hull, but he accidentally struck an iron bar on the underside, which the Turtle could not penetrate. After this failure, Lee’s inexperience as a submarine pilot showed. He failed to reattempt drilling and lost control of the Turtle, losing sight of the Eagle.

By the time he found it, sunrise was underway and so Lee fled. Upon passing Governor’s Island, he feared he was seen and detached the mine.

One hour later it exploded in the East River, proving that Bushnell’s mines worked, although the mission had failed.

Attempt #2

In late September 1776, Lee set out for another attempt on three British frigates anchored near Fort Washington, this time targeting the sterns at water level.

This mission was also a failure, and on October 9, the three frigates—the Phoenix, Roebuck and Tartar—sailed through a blockade outside Fort Washington and fired on American ships, sinking the sloop carrying the Turtle.

Bushnell salvaged it and brought the vessel back to his farm. However, his time in the Continental Army had rendered him extremely ill and this, combined with a lack of military funding, meant the Turtle was never used again. Its final fate is unknown.

Jefferson in Paris

In 1785, while living in Paris as Minister to France, Thomas Jefferson wrote to several contemporaries, eager for an account of Bushnell’s work nine years prior. This includes the letter to George Washington.

However, nobody could provide a detailed enough report on Bushnell’s experiments until Bushnell himself replied in 1787 with a description of the Turtle.

Washington's Response

In his response to Jefferson’s letter, Washington made his thoughts about Bushnell and his invention very clear:

Bushnel is a Man of great Mechanical powers—fertile of invention—and a master in execution—He came to me in 1776 recommended by Governor Trumbull (now dead) and other respectable characters who were proselites to his plan. Although I wanted faith myself, I furnished him with money, and other aids to carry it into execution. He laboured for sometime ineffectually, & though the advocates for his scheme continued sanguine he never did succeed. One accident or another was always intervening. I then thought, and still think, that it was an effort of genius…

"I then thought, and still think, that it was an effort of genius…"

- George Washington on Bushnell's submarine

Bushnell's Legacy

David Bushnell’s contributions to the Revolutionary War and to submarine technology are considerable; his ideas for a screw propeller and the use of water as ballast are both still used today. He invented the first working weaponized submarine and was the father of naval mine warfare.

Bushnell was far ahead of his time: It would be another 88 years after his attempt with the Turtle that the H. L. Hunley, built in Mobile, Alabama, during the Civil War, would become the first submarine to successfully attack and sink an opposing warship.

Today, Bushnell’s legacy endures in the U.S. Navy’s fleet of more than 70 sophisticated submarines—and in a short letter in Mount Vernon’s collection.

George Washington

Victorious general of the American Revolution, the first President of the United States, successful planter and entrepreneur. Explore the life and legacies of George Washington.

Learn more