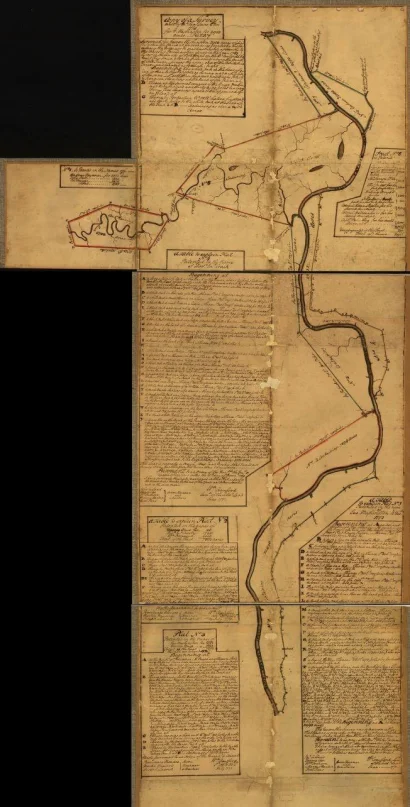

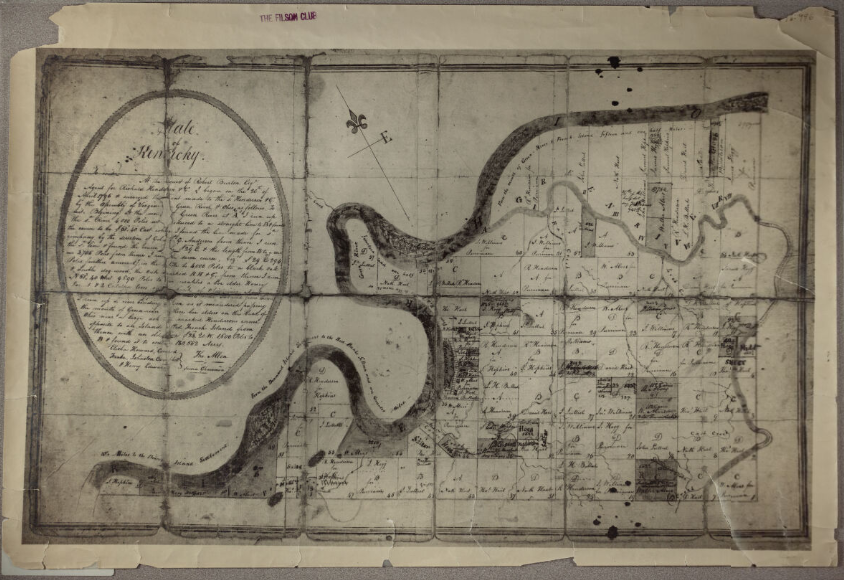

Though George Washington’s first land purchase was in 1750, in Frederick County, Virginia, his holdings soon encompassed lands in West Virginia and extended westward into Pennsylvania, New York and the Ohio River Valley. Land in what would become the state of Kentucky would be among Washington’s last acquisitions. Washington was interested in natural resources and the potential to rent land to tenants as migration to Kentucky increased after the American Revolution. However, much of this area was still in the control of various Indigenous nations such as the Shawnees, Cherokees, and Chickasaws. Washington’s land in Kentucky was located south of Louisville in what is now Grayson County. This parcel, about 5400 acres, was situated a short distance west from the mouth of Short Creek (now Spring Fork), on both sides of Hites Falls, about twelve miles from the “Falls of Rough.” In the decade after he purchased it, Washington struggled to obtain a clean title for the land.

Purchasing Property in Kentucky

Washington purchased western lands in the decades preceding his first purchase of Kentucky lands, and he described his speculation habits as, “It is true I am not fond of buying a Pig in a Poke.”1 However, after reading and studying John Filson’s The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke (1784), he became interested in purchasing land in Kentucky to access deposits of iron ore.2 Washington received two tracts of land in Kentucky from Henry Lee in exchange for his horse on December 9, 1788.3 The deed noted the land was worth some £600, but no money passed hands as Lee was given Washington’s Arabian stud named Magnolio. Washington never saw his tracts or any other Kentucky land; the closest he came was about forty miles from Huntington, West Virginia in 1770.4

Title Issues

In January 1789, Washington wrote to Lee asking him to provide clearer title to the land, stating that the papers Lee provided had met neither Washington’s “inclination nor expectation.” This matter took time to resolve, as the deed was not registered in Kentucky until July of 1799.5

In the intervening time, Lee had sold the same acreage to Alexander Spotswood, a cousin of Washington’s by marriage. Spotswood migrated to Kentucky for a new start and to see his newly acquired land holdings. While there in the spring of 1795, Spotswood met Washington’s nephew, George Lewis, who was acting on his behalf. The two soon determined that the land had been sold twice by Lee, once to Washington and then to Spotswood. Spotswood informed Washington of the duplicitous sale, writing, “I leave it to you to determine, what could be his motives for the double sale.”6

In response, Washington desired that Spotswood retain the title of the land when he purchased it from Lee. For his cooperation, Lee promised to sell him even better land in Kentucky. However, Spotswood cancelled the deal with Lee, which left the contested land in Washington’s hands. Until his death, Washington’s correspondence regarding his land in Kentucky dealt either with securing or with maintaining his title to the land or fruitless attempts to purchase an additional 300–acre parcel in the vicinity.

Washington’s Kentucky Lands

Throughout the 1790s, the land proved to be the proverbial thorn in Washington’s side as he sought to learn more about the land and repeatedly failed. The entire affair was a miasma of double-dealings, unclear warrants and titles, confusion, chicanery and lost dreams. Tasked as the first president, he did not have the bandwidth to attend to making the land profitable. However, as president he contributed to the development of policies that continued to favor American desiring to live in or purchase western lands over the territorial claims of Native American nations.

His last business with the land involved attempts to sell the property, but he still held title at the time of his death. By that time, he had never been able to rent the tracts, even as migration to Kentucky began to boom after it became a state in 1792. Around the time of his death, the property was valued at roughly two dollars an acre.7 The whole matter had brought neither pleasure nor profit. In the following decades, his nephews and great-nephews struggled to sell the lands.

Nancy Richey, Western Kentucky University, updated by Zoie Horecny, PhD., 26 September 2025

Notes:

1. “From George Washington to Henry Lee, 30 November 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 24 September 1788?–?31 March 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987, pp. 139–140.]

2. John Filson, The Discovery, Settlement & Present State of Kentucke, (1784).

3. “From George Washington to Henry Lee, 30 November 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 24 September 1788?–?31 March 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987, pp. 139–140.]; From George Washington to Henry Lee, 20 January 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 1, 24 September 1788?–?31 March 1789, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987, pp. 251–252.]

4. “[Diary entry: 8 October 1770],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 2, 14 January 1766?–?31 December 1770, ed. Donald Jackson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976, pp. 287–288.]

5. “From George Washington to Alexander Spotswood, 31 July 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 4, 20 April 1799?–?13 December 1799, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 218–219.]

6. “To George Washington from Alexander Spotswood, 21 September 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 29, 2017. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. William M. Ferraro, David R. Hoth and Jennifer E. Stertzer. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 721–723.]

7. "Enclosure: Schedule of Property, 9 July 1799," Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Calloway, Colin G. The First President, The First Americans, and the Birth of a Nation: The Indian World of George Washington. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Cook, Roy Bird. Washington’s Western Lands. Shenandoah Publishing: Strasburg, VA, 1930.

Dewees, Curtis. George Washington’s Kentucky Land. Lake Orion Books: Lake Orion, MI, 2005.

Jillson, Willard Rouse. The Land Adventures of George Washington. Louisville, KY: The Standard Printing Company, 1934.

Jillson, Willard Rouse. "George Washington’s Western Kentucky Lands.” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society 29, no. 89 (1931): 379-84.

"Deed of Henry Lee, of Westmoreland Co., Va. to George Washington, of Mount Vernon." Register of Kentucky State Historical Society 5, no. 15 (1907): 31-35.

Seeley, Samantha. Race, Removal, and the Right to Remain: Migration and the Making of the United States. The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2021.

Wilson, Samuel. “George Washington's Contacts with Kentucky,” Filson Club Quarterly 6, no. 3 (July 1932): 215-260.