While it’s only been a paid federal holiday since 1938, the Fourth of July has been celebrated by Americans stretching back to that first momentous day in 1776—and yes, fireworks were involved.

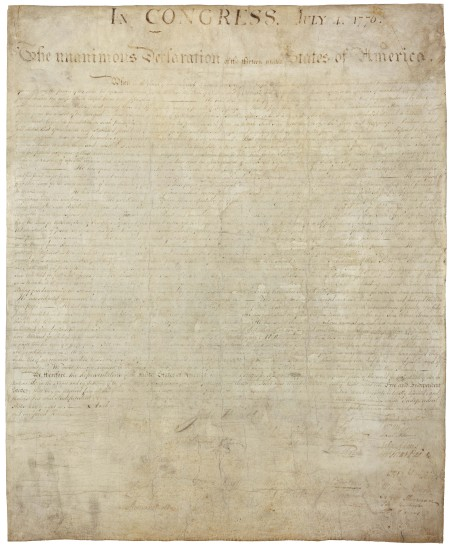

A Declaration

Today, the Fourth of July conjures up visions of parades, cookouts, waving flags, and brilliantly colored fireworks. Oh, the fireworks.

But how do our modern celebrations compare to the earliest Independence Day festivities?

Before the American Revolution, the King George III’s June 4 birthday was a celebration marked with bonfires, speeches, and the ringing of bells. But in 1776, as patriotic fervor swept through the colonies, praising birthday celebrations turned to mock funerals for the King.

So was the mood of the colonies on July 2, 1776, when the Continental Congress voted in favor of American independence. On July 4, after making several minor changes to Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, Congress officially adopted the document.

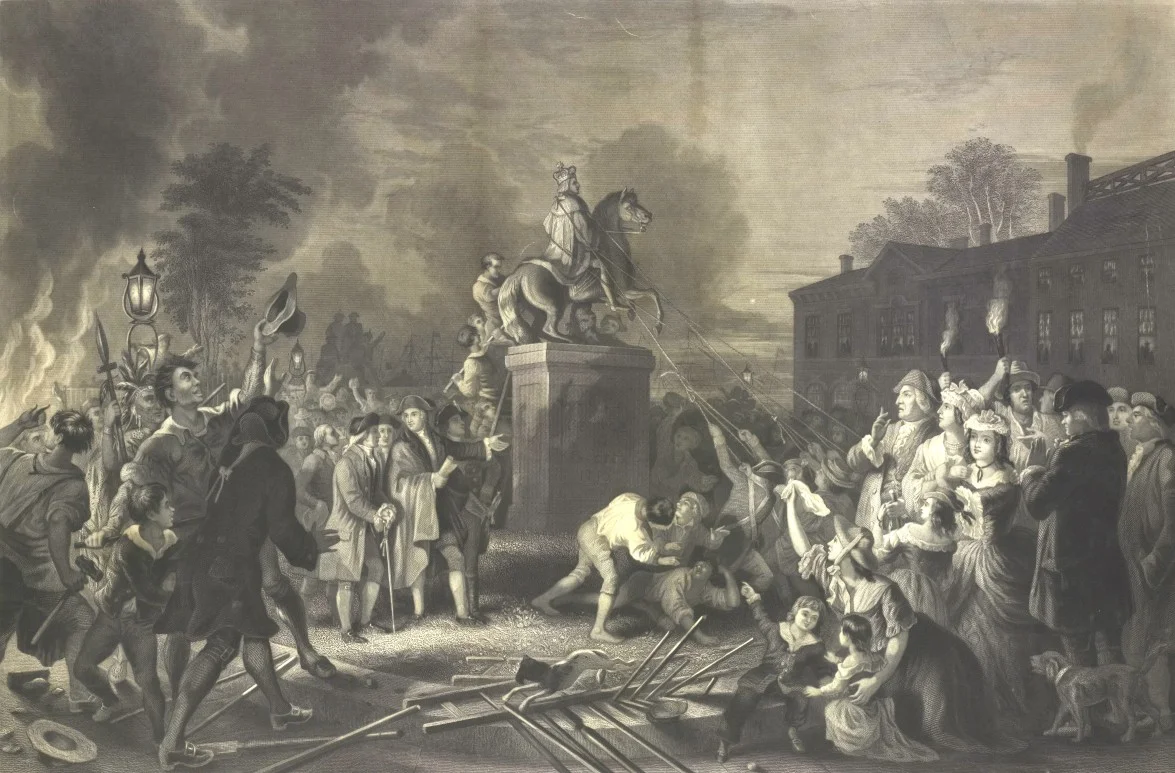

Losing Your Head

As told by Ron Chernow, author of Washington: A Life:

The troops rejoiced upon hearing the document. ‘The Declaration was read at the head of each brigade,’ wrote Samuel Blachley Webb, ‘and was received with three huzzas by the troops.’

Reading of the document led to such uproarious enthusiasm that soldiers sprinted down Broadway afterward and committed an act of vandalism: they toppled the equestrian statue of George III at Bowling Green, decapitating it, then parading the head around town to the lilting beat of fifes and drums.

Early Parties

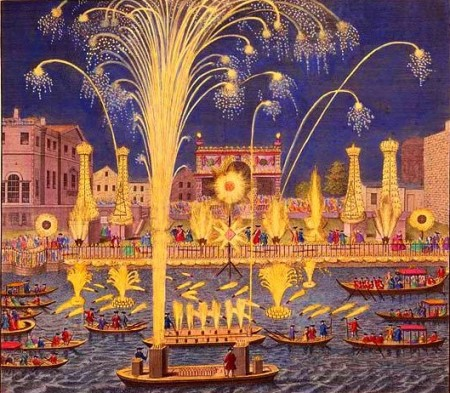

While many parades, bonfires, and the firing of muskets and cannons greeted the document’s public readings on July 8 of that year, the first organized July 4 celebration would take place in 1777 in Philadelphia and Boston.

According to the Pennsylvania Evening Post on July 5, 1777:

Yesterday the 4th of July, being the anniversary of the Independence of the United States of America, was celebrated in this city with demonstrations of joy and festivity. About noon all the armed ships and gallies in the river were drawn up before the city, dressed in the gayest manner, with the colors of the United States and streamers displayed. At one o’clock, the yards being properly manned, they began the celebration of the day by a discharge of thirteen cannon from each of the ships, and one from each of the thirteen gallies, in honor of the Thirteen United States … The evening was closed with the ringing of bells, and at night there was a grand exhibition of fireworks (which began and concluded with thirteen rockets) on the Commons, and the city was beautifully illuminated.

In Boston that same day, Col. Thomas Craft of the Sons of Liberty is said to have fired off fireworks and shells over Boston Common.

1781: Massachusetts becomes the first state to make July 4 an official state holiday.

Wait, they had fireworks?

July 4 is synonymous with fireworks. In fact, it’s estimated that Americans today spend an estimated $1 billion on fireworks each Fourth of July.

Some might be surprised to learn that the tradition of setting off fireworks, or miniature explosions, stretches back to the earliest days of American independence. And that fireworks themselves have a history that’s more than 2,000 years old.

In China around 200 BC, it was discovered that bamboo tossed into a fire would explode with a bang—the result of air pockets overheating inside the stalk. With the discovery of gunpower in China around 800 AD came the first man-made fireworks: hollowed-out bamboo filled with the explosive material. At this time, however, fireworks were still only enjoyed at ground-level.

Predictably, it wasn’t long before gunpowder became an essential part of warfare, used by the Chinese by 1200 to blast projectiles at enemies. But this “rocket” technology also led to the first aerial fireworks.

As diplomats and missionaries traveled between Europe and China in the following centuries, fireworks moved west, becoming an integral part of important European celebrations. It’s little surprise then that the American colonies adopted this tradition from their mother country and that fireworks were part of early July 4 celebrations.

Orange Fireworks

If you were transported to the earliest Independence Day parties, you might be disappointed by the lack of red, white, and blue exploding in the sky. That’s because colored fireworks weren’t commonplace for another 60 years, thanks to the addition of metals such as strontium and barium.

John Adams & the Fourth (or Second) of July

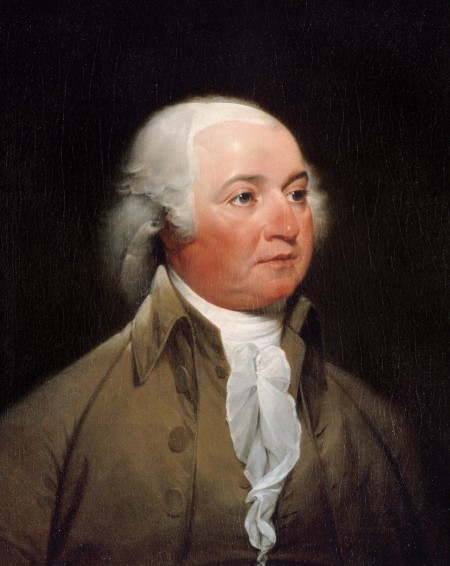

John Adams had an interesting relationship with the Fourth of July.

Following Congress’s July 2 vote in favor of independence, John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

Adams appears to have eventually capitulated to July 4 as Independence Day; according to David McCullough’s biography of the second president, when Adams, on his deathbed, was told it was the Fourth of July, he answered clearly, “It is a great day. It is a good day.”

Adams and Thomas Jefferson would both die on the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Five years later, another Founding Father and U.S. president, James Monroe, would also die on July 4.

Crowds at Mount Vernon

As July 4 as a holiday grew in its national significance, so, too, did Mount Vernon.

According to the “Fourth of July Encyclopedia” by James R. Heintze:

During the 1820s through 1850s it was a popular entertainment for groups of individuals to travel down the Potomac on steamers for a visit to Mount Vernon, to have dinner on the grounds there, pay their respects at the tomb, and to enjoy a panoramic view of the Potomac River. So many visitors took advantage of this entertainment that Bushrod Washington announced on July 4, 1822, that the unruliness of the crowds prompted him to issue a notice that large groups arriving by steam boat and engaging in ‘eating, drinking, and dancing parties’ on the grounds would be prohibited.

1870: The U.S. Congress makes July 4 an unpaid holiday for federal employees.

Did You Know?

Today, when Mount Vernon puts on a fireworks show, watching from the roof of the Mansion is a member of Mount Vernon’s Fire Department.

According to Joe Sliger, Mount Vernon’s Fire Chief and Vice President of Operations and Maintenance, it’s all part of the overall mission to safeguard George Washington’s historic home and estate. Although the fireworks are set off from a barge 500 feet into the Potomac River, Sliger explains that having a set of eyes on the Mansion roof, ready to react to any threat of fire, is vital.

“If there is a breeze in the wrong direction, it’s very possible that firework remnants could drift towards the Mansion and historic outbuildings,” Sliger says. “I was the guy on the roof for about 35 years, but now I’m handing off that responsibility.”

Assisting the roof man is a small fire team on the river shore, as well as a crew in the historic area and a firetruck on the South Lane (south of the Mansion).

1938: The U.S. Congress changes Independence Day to a paid federal holiday.

Sources

The Evolution of Fireworks. (2001, July 1). The Evolution of Fireworks |. https://ssec.si.edu/stemvisions-blog/evolution-fireworks

Why Do We Celebrate July 4 With Fireworks? (n.d.). History.com. https://www.history.com/news/july-4-fireworks-independence-day-john-adams

History of the Fourth of July - Brief History, Early Celebrations & Traditions. (n.d.). History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/july-4th

McCullough, David. 2002. John Adams. London, England: Simon & Schuster. Page 646.

Heintze, James R. 2007. The Fourth of July Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Page 191.

Enjoy July 4 at Mount Vernon

Celebrate our nation's independence at the home of the father of our country.

Learn more