Experts work to reveal the secrets beneath George Washington's original floor.

In a significant step, Mount Vernon’s Preservation team undertook the challenging task of temporarily removing the New Room's floorboards— an essential part of accessing and repairing the Mansion's underlying framing as part of the ongoing Mansion Revitalization Project.

The endeavor not only aimed to ensure the structural integrity of the historic home but also provided fascinating insights into the construction techniques used in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Is this Washington’s Original Floor?

In 2013, Director of Preservation Tom Reinhart set out to answer an intriguing question: Are the floorboards in Washington’s New Room original to the Mansion? Did Washington himself tread these very floors?

The longstanding belief was that the floor was a later replacement, as evidenced by the 19th-century nails securing it in place. Furthermore, the nails were driven through the face of each floorboard; if the floor was original, the Preservation team would expect to find that the boards were blind-nailed.

What is Blind Nailing?

Blind nailing, the most expensive and sophisticated method of floor installation in the 18th century, involved driving nails at an angle through the edge of the boards so that the nail was concealed once the next board was installed. Small wooden dowels between the floorboards helped hold them together. This technique secured the flooring without exposing the nails, providing a smooth and attractive surface. The result of this technique can be seen in the original flooring of Washington’s study.

The fact that the floors weren’t blind-nailed signaled that the floorboards had been previously lifted, but the exact timeline remained uncertain. And another question remained: When the original floorboards were lifted, were they put back down or replaced?

A few clues offered hints.

Gauging and Undercutting

The New Room flooring was gauged and undercut to ensure a level upper surface. This was standard practice in the 18th-century Chesapeake region. Floorboards were planed by hand on their tops and sides, but to save time (and therefore money) the undersides were left rough sawn. But to ensure a level floor surface, all of the boards still had to be exactly the same thickness where they crossed the floor joists. To accomplish this, a rabbet, or recess, was cut with a plane along the long edges of the underside of each board, making the boards exactly one inch thick along the edge. This is called gauging a board. The carpenter then adzed back–or undercut–each board where it touched the joists, using the gauge to ensure the boards were exactly an inch thick. “This is an 18th-century floor,” Reinhart says. “You don’t find gauging and undercutting in the 19th century.”

Evidence of Blind Nailing and Doweling

The Preservation team then found clear evidence that the floorboards had, in fact, once been blind-nailed and doweled.

Documentary Evidence

In a 1787 letter, a sawmill owner in Maryland responded to Washington’s request to purchase inch-and-a-half-thick plank, 24-foot-long, to be used as floorboards. This measurement, unusually long, matches the New Room’s existing floorboards. As Reinhart explains, it is highly unlikely that Washington’s original floorboards were removed, only to be replaced by salvaged 18th-century, 24-foot boards that had once been blind-nailed.

For Reinhart, this settled the question. These floorboards are original to George Washington.

The Removal Process: A Delicate Undertaking

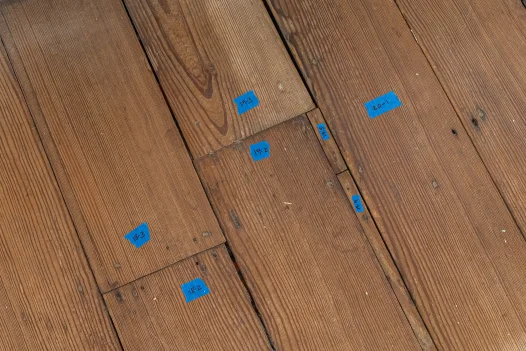

The first step was to document the floor in its existing condition—labeling each board and mapping the location of each nail.

With the aid of photogrammetry, the science of creating highly detailed 3D models by using multiple overlapping photos from different angles, the team ensured that the floor’s condition was preserved for future generations to study and appreciate.

The documentation process also created a reliable guide for the Preservation team to use during the floor’s re-installation.

Before removing the floorboards, it was necessary to remove the room’s mopboards (or baseboards)—a step akin to peeling back the first layer of the onion. With the mopboards carefully stored away, it was then possible to begin removing the room’s 57 floorboards.

Over the course of two weeks, Mount Vernon’s Preservation carpenters slowly released each floorboard from the underlying joists.

“Removing the floorboards is a fairly simple mechanical process—but it’s done very carefully,” explains Caroline Spurry, Mount Vernon’s architectural research manager. The boards had to be gently worked up, without pulling the nails through them. Sometimes, difficult nails that would not release from the floor joists had to be sawn through.

Discovery

Upon lifting the floorboards, the team discovered clear evidence of the original 18th-century craftsmanship. Cut dowels and remnants of the original blind nailing technique, including bent 18th-century nails, were still visible. This confirmed that the floorboards were indeed original and had been lifted and face-nailed (rather than blind-nailed) back into place during past repairs.

The Preservation team also confirmed that much of the framing beneath the floors had been replaced at one time. Using dendrochronology, the scientific process of dating wood by analyzing growth rings, the team determined that many of the room’s joists and its one surviving summer beam had been replaced in 1838. Such a large undertaking (similar to current work being undertaken during the Mansion Revitalization Project) would have required lifting the room’s mopboards and floorboards. The dendrochronology date, which pinpoints the boards’ earlier removal and reinstallation, allies with the physical evidence previously observed by the team, such as the types of nails used.

Next, carpenters will replace this non-original framing to restore the structural integrity of Washington’s New Room.

Floorboard Conservation

The floorboards were transported to the Preservation lab, where they underwent further analysis. Project Preservationist Clay Fellows, alongside Preservation carpenters and technicians, carried out an in-depth analysis of the floorboards, carefully documenting the location of all fasteners, including original 18th-century dowels. This assessment provided critical information for the project architects, helping them finalize the design for the new joists and summer beams to be installed underneath the New Room floor.

Contract conservator Andy Compton, along with the skilled assistance of former Mount Vernon carpenter Dave Weir, then undertook the task of cleaning and repairing the floorboards. This involved carefully plugging holes left behind by 19th-century nails on the face of each floorboard—bringing the floor closer to its original 18th-century appearance.

To further enhance authenticity, the floorboards will be reinstalled using the original blind nailing method.

Mansion Revitalization

As the Mansion Revitalization Project continues, each step not only ensures the structural integrity of the Mansion but also deepens the Preservation team’s understanding of 18th-century craftsmanship.

That is certainly true of the New Room’s floor—an extraordinary connection to the past that will be preserved for future generations.

An In-Depth Look

As Mount Vernon's Mansion Revitalization Project proceeds into 2026, take a deep dive into the various aspects—and unexpected discoveries—of this landmark preservation project.

Learn more