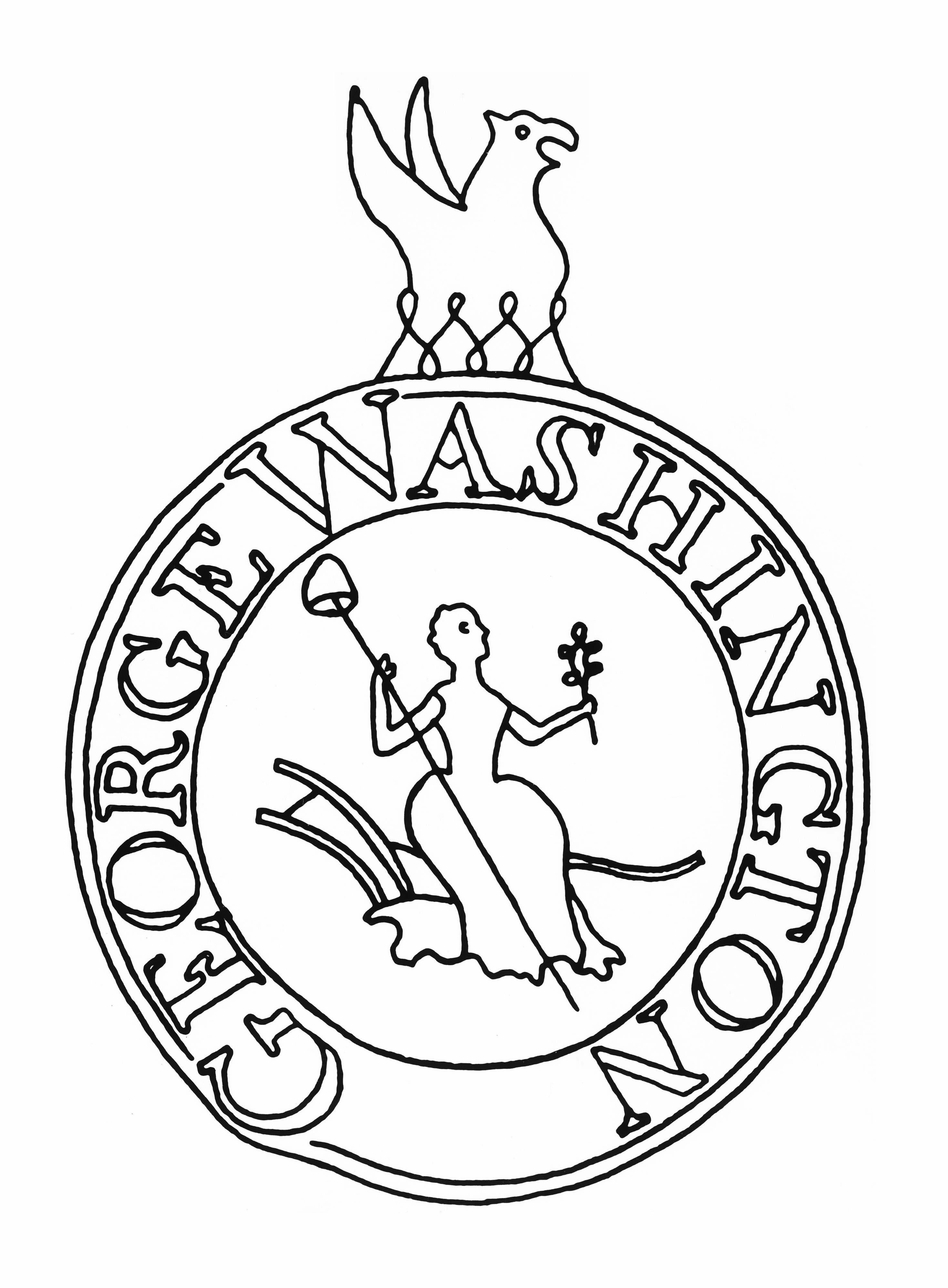

George Washington began using a watermark to authenticate documents that he authored during his first term as president. A watermark is a barely-visible design added to paper by the manufacturer that can indicate its features like size or quality. However, important figures like Washington could request unique watermarks for paper they intended to buy and use in an official capacity. Washington’s personal watermark was designed to embrace symbolism associated with the early Republic. It featured a central figure of Liberty leaning on a plow, holding a liberty pole with a cap aloft. The design is encircled by the lettering of "GEORGE WASHINGTON" surmounted by a griffin. These images all carried specific meaning.

Washington’s watermark featured a griffin in a crown, which is a part of the Washington family heraldry that Washington also engraved on other objects such as his personal silver.1 In the center, Lady Liberty is holding a liberty pole as indicated by the felt conical cap at its end known as a liberty cap. Lady Liberty leans upon a plow while holding a piece of wheat, representative of the importance of agriculture in the new nation and to Washington. The symbol of the plow was also was relevant to the Society of the Cincinnati as the tool was prominent in a scene engraved into medals worn by its members. Washington is often represented as Cincinnatus, a retired Roman general who led the Romans to victory against the Aequians, and returned to his farm or his “plow” after victory. Washington’s likeness to Cincinnatus is illustrated in a life-sized sculpture that features him standing in a plow by Jean-Antoine Houdon.

In 1790, Washington visited a papermill in New York and reflected on its operations and profitability.2 However, it is most likely two Pennsylvania-based papermakers connected to Washington provided his watermarked paper. James F. Magee or Henry Schütz's paper mill on Sandy Run, Whitemarsh Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania both supplied paper found at Mount Vernon. Papermills produced watermarks on paper by applying pressure of a projecting design mold impinged upon the surface of wet paper in order to control thinning during manufacture. Watermarking creates a translucent image with areas of lighter fiber density that is visible when the paper is held up to the light. Watermarks provided an early form of trademark for documents to deter counterfeits. Although watermark technology was linked to papermaking industry and papermakers, Washington became one of the first Americans who was not a papermaker that employed watermarks to set provenance for documents they issued.

Through the use of paper with his unique watermark, Washington set a presidential precedent for distinguishing documents created by the president. The watermark also indicated mail that was from the president, so that it would be exempt from postage fees as was customary for public officials. Before Congress issued a red inked “City of Washington” stamp for presidential use, Mount Vernon was the first location in the United States granted free franking privileges. Franking is a process in which a postage mark is applied to mail to indicate that it has been paid for, so with free franking privileges, Washington could send mail from Mount Vernon without charge. After Washington's death, when Congress was informed of the enormous amount of letters and packages during the period of mourning for Washington, the body passed an act granting the former First Lady Martha Washington franking privileges in 1800.

Originally researched by Meredith Eliassen Reference Specialist, Special Collections Department J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University, Updated by The Center for Digital History, 27 October 2015

Notes:

1. “George Washington to Isaac Heard, 2 May 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives; “George Washington to Robert Cary & Company, 6 June 1768,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. “[Diary entry: 24 April 1790],” Founders Online, National Archives.

Bibliography:

Bidwell, John. American Paper Mills, 1690-1832: A Directory of the Paper Trade, with Notes on Products, Watermarks, Distribution Methods, and Manufacturing Techniques. Darthmouth Press, 2013, 28-29.

Gravell, Thomas L., and Miller, George. American Watermarks, 1690-1835. New Castle, DE.: Oak Knoll Press, 2002.

Manca, Joseph. George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon. John Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Rickards, Maurice. Encyclopedia of Ephemera: A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator, and Historian. New York: Routledge, 2000.