George Washington’s Second Inaugural Address is, by a good margin, the shortest inaugural address ever delivered. Using just 135 words, Washington focused directly on what is, of course, the key element of the inaugural ceremony—the oath of office, and the responsibilities that that oath imposes—and said little else.

The speech seems to fit awkwardly in the company of inaugural addresses to come, ones that articulate policy visions and make grand statements of what the American nation should aspire to become. It has, on at least one occasion, simply been left out of a comprehensive account of presidential inaugural speeches.

Nonetheless, Washington’s Second Inaugural—all four sentences of it—merits our close attention. That it happened at all is itself important, the result of a thoughtful assessment by Washington and his cabinet, including Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and Henry Knox, of what was appropriate to the moment. And in the address’s focus upon the oath of office, Washington underscored an element of the presidency that can be overlooked: that the occupant of the office, while vested with substantial power, is also bound to adhere to the specific terms of an oath found in the Constitution itself.

There was no model to follow for what precisely should happen when a sitting president was elected to another term of office. The rituals of the American presidency were his to shape. In the election of 1792, Washington again had been elected president, unanimously, and again had great reluctance to take on the burdens of the office. There was a performative element in his repeated denials that he desired anything other than a long-delayed retirement, to be sure.

But it is also true that Washington primarily saw his continuation in the presidency as the performance of a duty owed to the nation, not as a personal accomplishment or, as so many subsequent presidents would see things, as a mandate to follow through on a specific political agenda. All of these things likely shaped his thinking about how, if at all, to talk publicly about his election to a second term in office.

The Cabinet's Opinion

On February 27, 1793, just days before the new term was to begin on March 4, Washington wrote to his Cabinet members and asked the four of them—Jefferson, Knox, Hamilton, and Edmund Randolph—to put their heads together and propose to him their “opinions as to the time, place & manner of qualification,” or oath. When they gathered at the War Office at 9:00 the following morning, the cabinet members discovered that they could not agree.

Jefferson and Hamilton, interestingly enough, both believed that Washington should simply take the oath privately, at his Philadelphia home, administered with no ceremony at all by Justice William Cushing of the Supreme Court, whose circuit included the nation’s capital. Knox and Randolph, on the other hand, advocated for a public event, in the presence of the members of Congress. In Jefferson’s recollection, Knox was “stickling for parade” and “got into great warmth” about the personal indispensability of Washington in the government’s survival: “it is the President’s character,” Jefferson remembered Knox arguing, “and not the written constitution which keeps it together.” Pomp and ceremony with Washington at the center, Knox believed, would serve a good purpose.

Ultimately, the four men recommended a public swearing-in, at noon, in the Senate Chamber with members of Congress and other dignitaries, such as foreign ministers, invited to observe. Hamilton acknowledged his initial concerns in a postscript he penned for President Washington, appended to the formal cabinet recommendation that Washington take the oath in a ceremony before Congress, but he did “think it right in the abstract to give publicity to the Act in question.” Washington agreed.

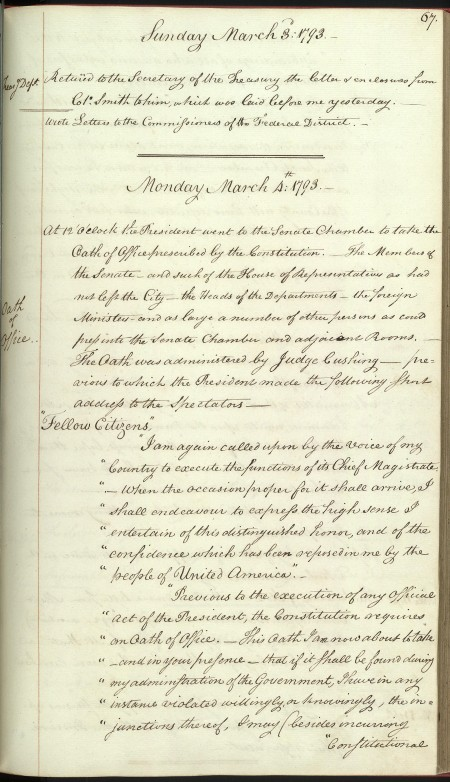

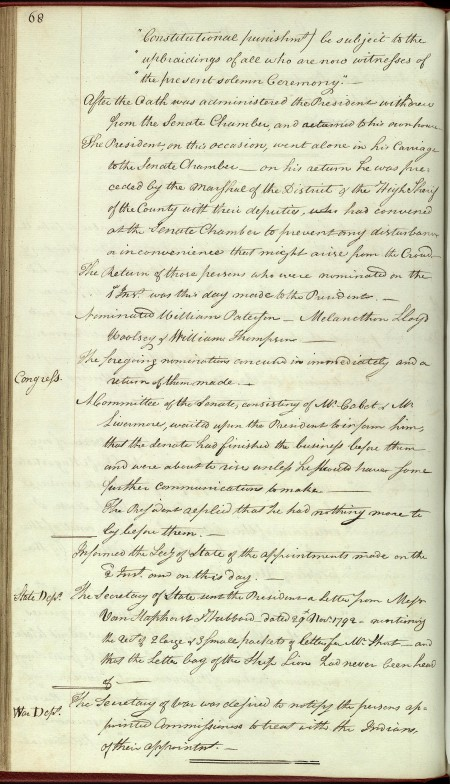

March 4, 1793

That Monday, Washington became the first man to be inaugurated president a second time. He also became the first president inaugurated on March 4, which would thereafter become one of the most important dates in the American political calendar—that is, until the ratification of the Twentieth Amendment in 1933, which moved the beginning of a presidential term to January 20. While the First Congress had been called to convene on March 4, 1789, Washington’s inauguration that year had come in late April, unavoidably delayed by the process of organizing the government. Beginning in 1793 and for nearly a century and a half, March 4 would become the standard date when one presidential term ended and another began.

Washington entered the Senate chamber precisely at noon, before an audience that included members of both houses of Congress, his own Cabinet, justices of the Supreme Court, foreign ministers, and “a number of private citizens, ladies and gentlemen,” according to the Philadelphia National Gazette. Vice President John Adams, who in many accounts is often mistakenly described as present, had left Philadelphia to attend to his wife, Abigail, during an illness. In his place, President Pro Tempore John Langdon called the proceedings to order by addressing Washington directly: “Sir, one of the Judges of the Supreme Court of the United States is now present, and ready to administer to you the oath required by the constitution, to be taken by the President of the United States.”

Washington stood and, to put it simply, briefly explained to Congress why it was that he had chosen to take the oath “in your presence.” He first noted that he would wait until “the occasion proper for it shall arrive” to go into more detail about “the high sense I entertain of this distinguished honor.” That time would come nine months later, in early December 1793, when Washington delivered his annual message to Congress and described both his “gratitude” and his “earnest wish for… retirement.”

On this day, at his second inaugural ceremony, Washington chose to focus on the oath itself and the public accountability it demanded. Should it be found that he had “in any instance, violated, willingly or knowingly, the injunction” of that constitutional oath, Washington asked to be held accountable, both to the strictures of “Constitutional punishment” (he refers here, of course, to impeachment) and to “the upbraidings of all who are now witnesses of the present solemn ceremony.” The man whom Americans most trusted to hold power spent the entirety of his Second Inaugural asking those around him to hold him accountable, both legally and morally, to the oath he was about to take.

Explore Washington's Full Address

The Oath of Office

Washington’s focus on the oath should not be surprising. Oaths and affirmations were extraordinarily important to the founding of the new nation, one that despite its powerful racial hierarchies and exclusions was nonetheless held together primarily by shared belief, not by history or an ethnic nationalism more typical to European states.

The War for Independence itself had driven this point home for Washington, who wrote to John Hancock in February 1777 to “strongly recommend every State to fix upon some Oath or Affirmation of Allegiance to be tendered to all the Inhabitants without exception, and to out law those that refuse it.” As a wartime leader in a chaotic environment in which allegiances were constantly up for grabs, Washington saw that “by our inattention” to oaths as a way to bind the people together “we lose a considerable Cement to our own Force, and give the Enemy an opportunity to make the first tender of the oath of allegiance to the King.” Interestingly, it was in this same letter that Washington advocated to Congress that steps be taken to inoculate the Continental Army against smallpox. The goal, in some ways, was similar: to prevent the spread of danger by securing people against it in advance.

With independence won and, after the Constitutional Convention of 1787, a new federal government created, the oath remained a crucial component in holding things together. In fact, the very first bill signed into law under the new government, on June 1, 1789, was “An Act to Regulate the Time and Manner of Administering Oaths,” which dictated the precise oath to be taken by all state and federal officials as called for in Article VI of the Constitution—everyone, that is, except the president, whose oath was found in the text of the Constitution itself. Now, nearly four years later and entering a second term in office, Washington took an opportunity to underscore just why those oaths were important. They bound the officers of the government to remain faithful and to fulfill their constitutional duties.

His short speech concluded, Washington stood opposite Justice William Cushing, who administered the oath. It is worth noting that the contemporary account in the Philadelphia National Gazette makes clear that Washington did not add the words “so help me God” at the end, further evidence that the myth that he had added those words four years earlier in New York is without any basis.

After taking the oath, Washington left “as he had come,” wrote the National Gazette, “without pomp or ceremony.” Though brief, though distinctly different from the addresses that would come from all those who would later assume the office, Washington’s Second Inaugural Address had one point to make, and it made it well: in a constitutional order full of checks, balances, and structural limitations on arbitrary power, the presidential oath was yet another safeguard to protect the American republic.

Kevin Butterfield, PhD

George Washington's Mount Vernon

Sources

“Cabinet Opinion on the Administration of the Presidential Oath, 28 February 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-12-02-0173.

“Cabinet Opinion on the Administration of the Presidential Oath, 1 March 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-12-02-0183.

"George Washington to the Cabinet, 27 February 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-12-02-0166.

"Inaugural Address, March 4, 1793, in secretary's hand (probably Tobias Lear).," Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/pin0201/.

“Notes on Washington’s Second Inauguration and Republicanism, 28 February 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0265.

"Washington's inauguration at Philadelphia" by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris. Pennsylvania Philadelphia, ca. 1947 (Cleveland, Ohio: The Foundation Press, Inc.) https://www.loc.gov/item/2004669765/.