In the spring of 1781, several enslaved individuals at Mount Vernon seized an extraordinary opportunity to liberate themselves.

As the British warship HMS Savage anchored in the Potomac River near the plantation, they made a bold and dangerous bid for freedom. The escapees, as recorded by Lund Washington, included: Lucy, Ester, Deborah, Peter, Lewis, Frank, Fredrick, Harry Washington, Tom, Sambo, Thomas, Peter, Stephen, James, Wally, Daniel, and Gunner.

Their flight was not only an act of self-emancipation—it was also deeply entangled in the politics and warfare of the American Revolution.

The British and the Promise of Freedom

Fleeing to the British—who still permitted slavery—may seem a paradox. But for many enslaved people, the British Army offered a rare chance at liberty. In 1775, John Murray, fourth Earl of Dunmore and Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to “all indented Servants & Slaves (the Property of Rebels) that will repair to His Majesty’s Standard—being able to bear Arms.” [1]

By April 1781, as war raged across the colonies, the HMS Savage—under the command of Captain Richard Graves—appeared in the Potomac near Mount Vernon. The ship had already burned homes across the river in Maryland and now demanded provisions from the Washington estate. Lund Washington, George Washington’s distant cousin and Mount Vernon's acting manager, initially refused the request.

But the threat of destruction loomed. Captain Graves moved the vessel closer and warned that Mount Vernon would meet the same fate. Fearing for the plantation, Lund boarded the ship and offered “a small present of poultry” as a peace gesture.

Graves, in turn, “expressed his personal respect for the character of the General,” praised Lund’s handling of the situation, and “assured him nothing but his having misconceived the terms of the first answer could have induced him… to entertain the idea of taking the smallest measure offensive to so illustrious a character as the General.” [2]

Graves also claimed that “real or supposed provocations… had compelled his severity on the other side of the river.” After this exchange, Lund returned to shore and “instantly despatched sheep, hogs, and an abundant supply of other articles as a present to the English frigate.”

This exchange spared the estate—but not without consequences.

“That Which Gives Most Concern…”

At the time, George Washington was away, commanding the Continental Army from his headquarters in New Windsor, New York. Lund’s decision to negotiate with the enemy—and the subsequent escape of 17 people—infuriated him.

“That which gives most concern,” Washington wrote on April 30, 1781, “is, that you should go on board the enemys vessels & furnish them with refreshments. It would have been a less painful circumstance to me, to have heard, that...they had burnt my House, & laid the Plantation in Ruins.” [3]

Washington was not only alarmed by the escape but also by what he viewed as a breach of loyalty and principle in cooperating with the enemy.

Who Escaped?

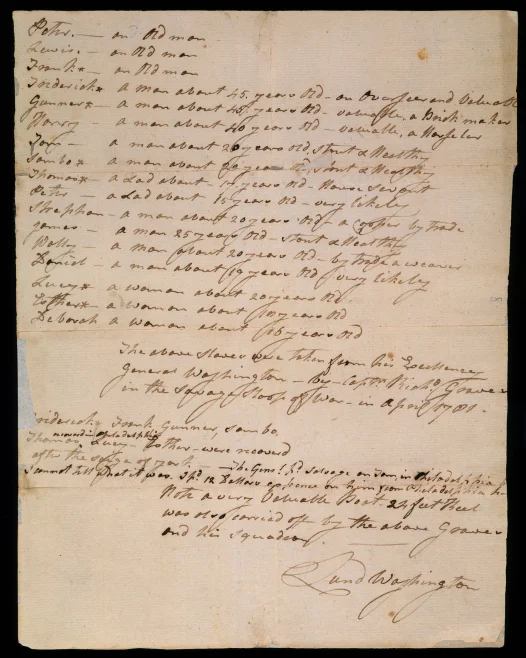

Shortly after the escape, Lund Washington compiled a list describing the individuals who had boarded the HMS Savage. While details vary, the list provides rare insight into their lives:

- Peter, Lewis, and Frank were described as “old.”

- Frederick, a 45-year-old overseer, and Gunner, a brick maker around the same age, were both considered highly valuable.

- Harry Washington, about 40 years old, was listed as a “Horseler.”

- James (25), Tom (20), and Sambo (20) were noted as “stout & healthy.”

- Stephen, a cooper, and Wally, a weaver, were each around 20.

- Thomas, a 17-year-old house servant; Peter (15); and Daniel (19) were described as “very likely.”

- Lucy (20), Ester (18), and Deborah (16) were listed by age alone, without occupational descriptors. [4]

While the exact circumstances of each individual’s escape remain uncertain—particularly for Harry Washington and Deborah Squash, who may have left earlier—the moment marked a powerful act of collective resistance.

After the Escape

The fate of those who fled varies:

- Seven individuals—Thomas, Fredrick, Frank, Sambo, Lucy, Ester, and Gunner—were recaptured and forcibly returned to Mount Vernon after the British surrender at Yorktown in late 1781.

- Harry Washington, Daniel Payne, and Deborah Squash were among those evacuated by the British to Nova Scotia, and Harry later emigrated to Sierra Leone, where he helped lead a rebellion against British colonial rule. [5]

- The remaining seven—Peter, Lewis, Tom, Peter, Stephen, James, and Wally—disappear from the record. They may have died in wartime disease outbreaks or gone on to lives of freedom, though their stories remain untold.

Today, their names and actions continue to shape our understanding of Mount Vernon’s history and the larger American story.

Resistance and Punishment

People at Mount Vernon found many ways to resist bondage and challenge George Washington’s authority.

Learn moreReferences

- John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775; quoted in: Mary V. Thompson, “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret”, University of Virginia Press, 2019.

- George Grieve, “Notes on Conversation with Lund Washington,” in Travels in North America... by the Marquis de Chastellux (Vol. 2), 1963.

- George Washington to Lund Washington, April 30, 1781, Founders Online.

- Lund Washington, List of enslaved people escaped to HMS Savage, 1781, Mount Vernon Digital Collections.

- Cassandra Pybus, “Washington’s Revolution,” Atlantic Studies, Vol. 3 No. 2, October 2006, doi.org/10.1080/14788810600875414.