On May 28, 1754 Virginia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel George Washington and Mingo chief Tanacharison, also known as “Half-King,” led a party of roughly forty men in a raid against twenty-nine French soldiers in present-day western Pennsylvania killing ten and capturing twenty-one. To many, this confrontation at Jumonville Glen represented the beginning of the Seven Years’ War in North America. In the following weeks, French retaliation for the attack resulted in the Battle of Fort Necessity and British defeat under Washington.

Washington’s Allegheny Expedition

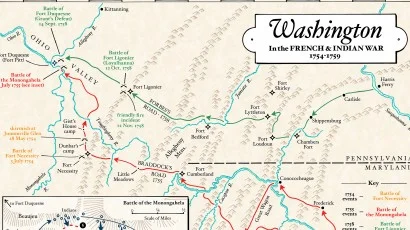

By 1753, the upper Ohio River Valley became an increasing source of friction between French and British imperial ambitions. In October, following reports of the French constructing forts in the region, Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie dispatched Washington with a request for French withdrawal.1 After a three month journey referred to as the Allegheny Expedition, Washington reported to Dinwiddie that the French had no intention of departing the Ohio and were in fact adding troops to the region.2 In response, Dinwiddie ordered the newly raised Virginia Regiment under Colonel Joshua Fry to the frontier. After raising and equipping his force in Alexandria, Washington was to proceed with an advance portion of the regiment and aid Captain William Trent in establishing a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, where the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers converge.3

Washington’s Return to the Ohio River Valley

When Washington and his roughly one hundred and fifty men arrived at Wills Creek (present-day Cumberland, Maryland) in April 1754, they learned that 1,000 French soldiers under the command of Captain Claude-Pierre Pécaudy, sieur de Contrecœur had overrun the scant force of British already working at the Forks.4 Washington ordered his small command over the Allegheny Mountains in the hopes of establishing a defensive position along Red Stone Creek and demonstrating British resolve to fight alongside their Native American allies in the region. These allies included “Mingos,” or individuals Iroquois Nation, many of which were Senca and Cayuga, who migrated to the Ohio River Valley. For the next month, Washington’s one hundred and fifty men worked to open a road from Will’s Creek to their position in the Great Meadows (near present-day Farmington, Pennsylvania) while awaiting reinforcements.5

Jumonville Glen Skirmish

On May 27th, reports came into Washington’s camp of a force of fifty French soldiers less than fifteen miles from his position. Washington met with Tanacharison, and the two of them decided to take a portion of their troops and meet the French. Throughout the night, the column of roughly fifty men traveled single file through the inky wilderness, with seven Virginians getting lost along the way. The next morning, they discovered the French in a sheltered glen hidden from the main trail, Washington describing the encampment as “lodgment which they did abt half a mile from the Road in a very obscure place surrounded with Rocks.”6 Tanacharison’s directed Mingos under his leadership behind the French position, while Washington’s Virginias advanced towards the front of the glen. With Washington in the lead, the Virginians swiftly moved on the French position and the resulting engagement lasted only fifteen minutes before the French surrendered.7

The details of the “battle” continues to plague Washington’s legacy to this day. By his own account, upon sighting the British advancing on their position, the French soldiers immediately went for their weapons prompting Washington’s soldiers to fire in their own defense. According to the French, they had no knowledge of the British soldiers until the Virginians fired their first volleys.8 Since Great Britain and France were not at war, the French argued, the actions of Washington’s soldiers amounted to murder. This was especially egregious since the French asserted they were an ambassadorial delegation under the command of Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville, the commander of the French party and a mortal victim of the skirmish. To his death, Washington argued that, by hiding in the woods near the Virginian position for many days rather than openly acknowledging their presence, the French were acting in a military capacity, not a diplomatic one.9 As such, he and his soldiers were in danger of the French, and had a right to defend themselves and their camp.

The treatment of French wounded following the engagement also plagues Washington’s reputation. French versions of the battle’s aftermath, related to them by a soldier that escaped, stated that the Virginians fired on the wounded French, and would have killed more if the Mingos had not intervened. Washington’s account states that the Mingos killed and scalped the French wounded, later sending those scalps as proof to their allies that war had begun and requesting their assistance in the conflict.10

French Retaliation

Just over a month after the skirmish at what became known as Jumonville Glen, 600 French soldiers and their Native American allies overwhelmed Washington’s position at Fort Necessity in the Great Meadows. Washington described the difficulty of the battle, “We continued this unequal Fight, with an Enemy sheltered behind the Trees, ourselves without Shelter, in Trenches full of Water, in a settled Rain, and the Enemy galling us on all Sides incessantly from the Woods.”11 The capitulation was especially awkward because the French force was led by Jumonville’s half-brother, Louis Coulon de Villers. During the surrender negotiations, the French had Washington sign a statement asserting that he and his troops had assassinated Jumonville, which was attributed to a translation error made by the British translator Jacob Van Braam.12 France later used the Jumonville Glen skirmish as causus belli to engage in the Seven Years’ War in North America.

Joseph F. Stoltz III, Ph.D. Digital Historian Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon

Notes:

1. “Instructions from Robert Dinwiddie, 30 October 1753,” Founders Online, National Archives.

2. “Journey to the French Commandant: Narrative, 1753-1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

3. “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 25 April 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

4. “Expedition to the Ohio, 1754: Narrative,” Founders Online, National Archives.

5. Ibid.; “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 29 May 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

6. “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 29 May 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

7. Papiers Contrecoeur et Autres Documents concernant Le Conflit Anglo- Francais sir L'Ohio de 1745 a 1756, ed. Fernand Grenier, (Quebec: Laval University Press, 1952).

8. “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 29 May 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

9. “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 29 May 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives.

10. “I., 19 July 1754, Account by George Washington and James Mackay of the Capitulation of Fort Necessity” Founders Online, National Archives. When Washington reported in to his Virginia superiors, he overstated the French forces, claiming they had 900 troops. Later scholarship shows that the number was close to 600. Edward G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (New York: Random House, 2005) 42-45; Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Vintage Books, 2000) 63-65.

11."I., 19 July 1754, Account by George Washington and James Mackay of the Capitulation of Fort Necessity” Founders Online, National Archives.

12. Ibid.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Knopf Double Day Publishing Group, 2007.

Axelrod, Alan. Blooding at Great Meadows: Young George Washington and the Battle That Shaped the Man. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press, 2007.

Alberts, Robert C. A Charming Field for an Encounter: The Story of George Washington's Fort Necessity. Washington, D.C.: Office of Publications, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1975.

Calloway, Colin G. The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of a Nation. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Clary, David A. George Washington's First War: His Early Military Adventures. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

Hindman, William Blake. The Great Meadows Campaign and the Climactic Battle of Fort Necessity. Leesburg, VA: Printed by Potomac Press, 1967.

Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. New York: Random House, 2005.

Links:

Jumonville Glen Subunit of the Fort Necessity National Battlefield, Pennsylvania