Mount Vernon's landscape was George Washington’s carefully composed “pleasure grounds,” the highly cultivated, ornamental grounds created for the enjoyment of his guests. He instructed the creation of sweeping lawns, groves of trees, walled gardens, serpentine paths, and vistas that we enjoy today.

The buildings and grounds surrounding the Mansion lacked a cohesive design, having been developed over time with more of an eye toward practical necessity than beauty. Washington set out to implement a unified scheme for a “pleasure grounds” that would enhance the natural beauty of the place.

“In a word the garden, the plantations, the house, the whole upkeep, proves that a man born with natural taste can divine the beautiful without having seen the model. The G[enera]l has never left America. After seeing his house and his gardens one would say that he had seen the most beautiful examples in England…”

–Julian Niemcewicz, 1798

Aesthetic Features of Washington's Landscape

Modern visitors who photograph Mount Vernon’s scenery are often surprised by how easy it is to take perfect, natural-looking pictures. What many may not realize is how carefully George Washington planned his landscape to be picture-perfect, inspired by 18th-century theories about art and aesthetics.

English garden writers encouraged a naturalistic approach to landscape design. In place of the symmetry, balance, and clearly defined patterns found in earlier designs, they valued variety, surprise, and concealment of boundaries. To update Mount Vernon in the new fashion, Washington installed such admired naturalistic features as sweeping lawns, groves of trees, wildernesses, serpentine paths, vistas, and hidden ha-ha walls. He also retained some earlier design features, including a formal geometric plan for his ornamental flower garden and a symmetrical arrangement of plantings on either side of the west lawn.

Working with far fewer acres than English country estates, Washington lacked the option of completely separating the pleasure grounds from the working parts of his plantation. Instead, he arranged walls, groves, and shrubberies to cleverly keep the stable, laundry, blacksmith shop, and slave quarters hidden from the view of the Mansion and pleasure grounds. Ever practical, he incorporated vegetables, fruits, and berries within his ornamental flower garden. Such details reveal George Washington’s personal involvement and innovation, drawing ideas from English sources but adapting them to suit his own tastes and needs.

View to the North from the Lawn at Mount Vernon by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1796. This unique scene captures the Washington family taking tea on the piazza, enjoying the respite provided by George Washington’s carefully staged, picturesque river view. No other image conveys so vividly the Mount Vernon landscape’s importance to George Washington—offering quiet repose and the grandeur of nature to invigorate the father of his country. (MVLA)

By allowing viewers to see extended distances, spyglasses performed both aesthetic and practical functions. The standing man in Latrobe’s piazza scene peers toward the river – is he examining details of the carefully composed landscape, or searching for oncoming ships? Could this spyglass – thought to be one of several owned by George Washington – be the spyglass shown in the drawing? (MVLA, [W-644])

Picturesque, Natural Compositions

Approaches to landscape design evolved over the course of the 18th century from the formal clipped hedges, radiating walks, and contrived geometry of an earlier era to more natural compositions. Proponents of this shift emphasized the use of curved lines to give a more natural appearance to landscape design. British landscape architects were inspired by the paintings of 17th-century French artist Claude Lorrain, and they replicated his dramatic style by framing distant views with trees and landscape elements in the foreground. Landscape theorists believed that garden design should simply improve the beauty already provided by nature.

George Washington demonstrated an interest in picturesque landscapes early in life, ordering “A Neat Landskip” after Claude Lorrain for Mount Vernon’s Front Parlor in 1757. Many of the prints Washington purchased for the Mansion also featured the picturesque scenes that he admired in both art and landscape design.

The View to the West

The oval window at the middle of the Mansion’s pediment frames this spectacular view toward the west gate, nearly a mile away. This long, narrow clearing was the estate’s primary and most impressive “visto.” Staked out by George Washington in 1785, it stretched on a line from the Mansion’s front door. Washington designed several other secondary vistas, created and maintained by his enslaved workforce. They cleared brush from tree lines and planted additional varieties of trees to create richly textured views.

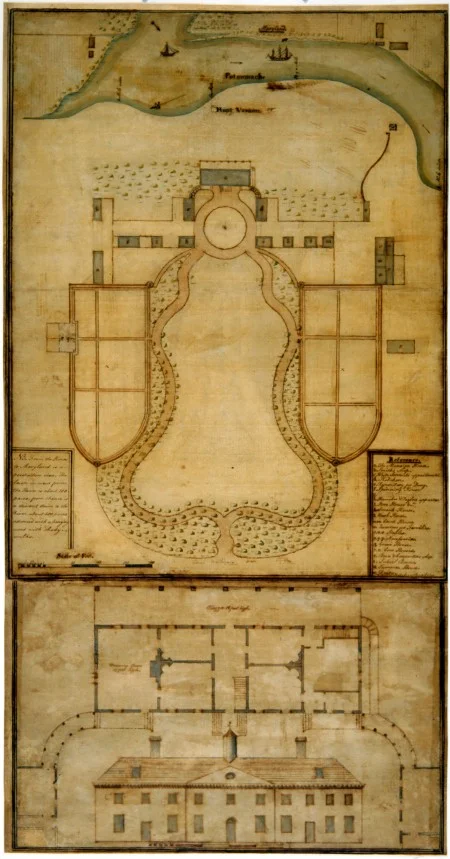

The Vaughan Plan

Washington’s most significant landscape improvements took form between 1785 and 1787. During this break from public affairs, rarely a day passed without some work on his landscape projects. He rode through the woods to mark specimen trees for transplanting, directed gardeners and enslaved workers to plant hedges and prune shrubs, and wrote letters requesting seeds or cuttings of unusual plants. When Washington departed to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, his work on the Mount Vernon landscape was nearly complete, needing only the passing seasons for plantings to become established.

By 1787, George Washington had installed the major elements of his landscape design, as beautifully recorded by his friend and admirer, Samuel Vaughan.

An enthusiastic supporter of the American cause, the wealthy English merchant Samuel Vaughn arrived in Philadelphia in September 1783, just days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris formally ended the American Revolution. Vaughan had long admired General Washington and met him through the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture.

Vaughan spent several days at Mount Vernon that summer, while Washington was in Philadelphia, presiding over the heated debates of the Constitutional Convention. The General was then beginning to think about improvements he wished to make at Mount Vernon, and Vaughan proved a valuable source of information on the latest English ideas on both landscape design and interior furnishings.

Vaughan explored the estate, took detailed measurements of the Mansion and surrounding features, and made a rough sketch in his small travel notebook. He subsequently compiled this information into a large finished drawing, which he presented to the General as a gift.

Known today as the “Vaughan plan,” this bird’s-eye view precisely captures George Washington’s “grand design” for his “pleasure grounds.” Preserved among his papers after his death, the original drawing returned to Mount Vernon in 1975. Vaughan’s drawing provides invaluable documentation about the appearance of the estate, guiding the restoration of landscape elements that have disappeared over time.

Samuel Vaughan’s drawing shows the major elements of George Washington’s pleasure grounds. A lettered key in the lower right identifies specific features: from the top, the sweeping curves of the Potomac River, the east lawn, and groves of trees at both ends of the Mansion. The formal geometry of the circle and the straight lines of outbuildings and garden pathways contrast strongly with the serpentine walks that border the central bowling green. Washington himself praised Vaughan’s accuracy, noting only that the trees came too close to the gate at the bottom of the drawing.

learn more about the vaughan plan

The View to the East

The breathtaking panorama of the Potomac River seen from the piazza is the most impressive view at Mount Vernon. While this scene appears to be completely natural, it is actually the result of George Washington’s carefully managed design scheme, incorporating popular English landscape features.

Learn moreHa-Ha Walls

Washington installed a “ha-ha,” or walled ditch, just below the crest of the hill, out of sight from the piazza. While keeping livestock out, the ha-ha fostered the illusion that the manicured lawn continued toward the river. Further down the slope, he maintained a cluster of neatly trimmed trees that were never allowed to grow high enough to obscure the view of the Potomac—a landscape feature known to Englishmen as a “hanging wood.” Finally, when planning the piazza itself, Washington broke the rules of classical architecture by using very thin, square columns that obstructed the view as little as possible.

Phases of Landscape Development

Imposing Order

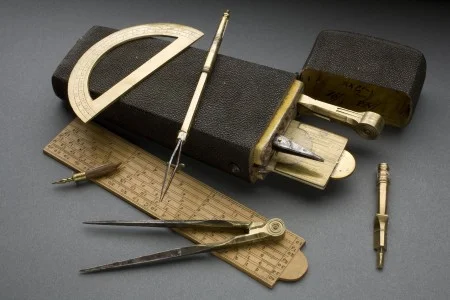

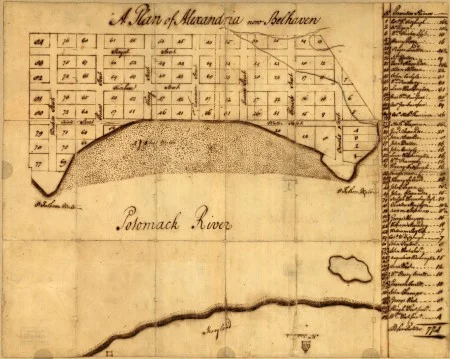

George Washington developed a thorough knowledge of Mount Vernon’s topography through the countless surveys he made of his land. This understanding allowed him to highlight the natural advantages provided by the rolling hills and to calculate sightlines for his vistas. He likely put these surveying skills to use to create a working plan that guided him as he laid out his design.

The design of Washington’s landscape functions like his surveys and town plans, imposing manmade order on the natural world by dividing land into discrete plots. Rather than wholeheartedly embracing the fully formed naturalism of the British picturesque, Washington picked the elements that appealed to him and slotted them into his own design, adapting them to fit his circumstances. When the landscape is viewed from above, the layout appears almost completely symmetrical. Buildings are aligned on either side of the carriage circle; the curvature of the bowling green and serpentine walks is identical; and two lozenge-shaped gardens border the composition.

The careful landscape design overlay another, less easily visible division of spaces – between separate but intersecting zones—the pleasure grounds of the elite white planter and the working landscape of the enslaved community. Washington maintained strict boundaries between these two zones, highlighting the hierarchical social order of a Virginia plantation and emphasizing his own authority over the domestic landscape.

Developing a Vision

Although George Washington never traveled to Great Britain, his landscape design is closely linked to the picturesque landscape that developed there. Washington learned of current fashions from gardening books imported to America, through correspondence with other gardeners, and by observing current trends implemented by his contemporaries. In 1784 and 1785, as he thought through the challenge of designing Mount Vernon’s pleasure grounds, Washington wrote letters to other gardeners requesting their advice on the best practices in landscape design.

The vast majority of gardening manuals and design books imported to America were written by British authors and provided advice specific to the growing conditions and landed estates found in Great Britain. Washington adapted this advice to an American context, where gardens were smaller and more compact. He also maintained an experimental garden where he could test the growing methods recommended in the garden manuals and determine appropriate techniques for American soil.

Washington was influenced by New Principles of Gardening by Batty Langley. The book offers practical suggestions for creating a more naturalistic garden by including good shade, uninterrupted views, and frequent “irregularities,” while avoiding stiffness and tiring repetition.

George Washington's compass allowed him to lay out straight lines in his gardens and to determine boundaries for his surveys. The sights allow the user to determine the position of a line in relation to magnetic north. MVLA, Gift of Judge Charles Burgess Ball, 1876, [W-579/A-B]

Finding Inspiration

George Washington developed a keen eye for landscape design through his travels. In addition to consulting garden design books, he drew inspiration from the natural wonders of the American landscape. As he traveled west, as a young man, he commented upon the grand drama created by scenes viewed from high prospects, like mountains. He would later use this concept to advantage when clearing the views at Mount Vernon.

Wherever Washington traveled, he often stopped to see the best gardens of the local elite. He determined what he liked or did not like about a particular estate and recorded these observations in his journal. When Washington visited the famous gardens of botanist John Bartram outside Philadelphia, he observed that although the botanical garden was brimming with exotic plants, it “was not laid off with much taste, nor was it large.”

After his visit to Mount Clare, the Baltimore home of Margaret Tilghman Carroll, Washington was so impressed with her greenhouse that he based elements of his design on hers.

Landscape Development at Mount Vernon

Dean Norton, Director of Horticulture at George Washington's Mount Vernon, discusses how George Washington shaped the landscape at his Mount Vernon home.

The Bowling Green

As the central element of his landscape composition, George Washington devised a level, well-manicured lawn, admiringly described by a French nobleman as “a kind of courtyard with a green carpet.” While modern visitors may be accustomed to such wide expanses of evenly trimmed grass, 18th-century lawns were expensive to plant and required extensive labor to maintain. After leveling the ground for the guitar-shaped bowling green west of the Mansion, Washington sought enough English or Goose grass seed “as would sow five acres,” noting that “the kind I want is that which affords the best turf for walks and lawns.” Although Clement Biddle, Washington’s agent in Philadelphia, was easily able to find grasses suitable for agriculture, he had difficulty procuring seed for a lawn, there being little demand for ornamental grass in America.

Once the grass was planted, keeping it cut was not nearly as simple as getting out a lawnmower. The day before a grass cutting, gardeners smoothed the ground with a large stone roller to create an even surface for cutting. The next day, gardeners cut the grass by swinging the blade of a freshly sharpened scythe back and forth in a repetitive motion. Maintaining an even surface and uniform height required skill, and only the most experienced gardeners were allowed to cut the grass. As they worked their way across the bowling green, the gardeners repeatedly paused to sharpen their blades with stones carried on their belts.

Serpentine Paths

To tie together the different elements of his landscape design, George Washington laid out “serpentine paths” hugging the contours of the bowling green. These gently curving gravel walkways guided visitors through Mount Vernon’s pleasure grounds, revealing carefully arranged scenes around every bend. The gentle S-curves of the serpentine pathways gave the landscape a more natural appearance, strongly contrasting with the straight, formal walks of most 18th-century American landscapes.

Along the serpentine paths, Washington planted forest trees, which framed the views while offering welcome shade, These trees were planted more densely during Washington’s lifetime, prompting at least one visitor to marvel at what seemed to him a “thousand kinds of trees, plants, and bushes.”

The Potomac River provided a ready supply of smooth river stones to gravel the many paths. Found during an archaeological dig of the upper garden, this gravel was prepared by Mount Vernon’s gardeners by passing it “through a wooden sieve, to take out Stones of too large a size” before spreading the gravel in the wide paths and packing it down with a stone roller.

Walking west from the Mansion along these paths, Washington’s guests first encountered two “shrubberies,” dotted with bursts of color created by flowering shrubs. Turning the bend of the upper path, a pair of gates came into view, offering the upper garden and greenhouse to exploration. Further along, visitors encountered Washington’s “wildernesses,” which were so thickly planted with evergreens that the sun barely shone through. A pathway snaking through each wilderness allowed visitors to explore these spaces before emerging again onto the serpentine walks as they opened onto the bowling green, with the prospect of the Mansion on one side and the vista to the west gate on the other.

On either side of the bowling green, George Washington built brick-walled gardens of approximately one acre each. The brick walls protected the plantings from wildlife and also retained heat, creating a micro-climate that kept the interior warmer and extended the growing season for delicate plants. The north, or upper garden, was the more ornamental of the two and was intended to be a highlight of a walk through the pleasure grounds. Entering from the bowling green, the greenhouse dominated the view of large planting beds and gravel paths. The south, or lower garden, was dedicated entirely to food production. It received the best direct sunlight, with two terraces set into the side of a hill.

The Gardens at Mount Vernon

George Washington's well-ordered gardens provided food for the Mansion's table and were also pleasing to the eye. Eighteenth-century visitors to Mount Vernon were delighted by bountiful offerings of fresh vegetables and fruits, and reveled in after-dinner walks amongst all manner of opulent flowering plants.

explore the four gardensCultivating the Earth

To build and maintain Mount Vernon’s pleasure grounds and produce gardens, George Washington used the labor of both free and enslaved workers. As Washington developed his landscape between 1785 and 1787, he directed the work of the “Mansion house people,” the enslaved persons on the home farm, as they transplanted the trees, built the brick walls, and graveled the serpentine walks.

enslaved workers at mount vernon

In 1789, as Washington headed to New York to assume the presidency, he sought, “a compleat Kitchen Gardener with a competent knowledge of Flowers and a Green House.” The following year, Washington hired John (Johann) Christian Ehlers, a well-trained gardener who had served in royal gardens in his native Germany. In Washington’s absence, Ehlers showed visitors around the Mount Vernon estate, pointing out exotic plants by their Latin names. The German gardener typically worked with two or three enslaved laborers, including at various times Frank Lee, Harry, Sam, George and the former cook, Hercules. Enslaved children at the Mansion House farm performed smaller tasks such as raking grass clippings or picking up fallen sticks.

Returning from the presidency in 1797, George Washington parted ways with his German gardener, John Christian Ehlers, after almost eight years. Washington had grown weary of Ehler’s inability to “refrain from Spirituous liquors” and his propensity toward idleness.

Properly trained gardeners were scarce in the United States, so Washington wrote to James Anderson, a friend and economist living in Scotland, requesting assistance in finding a gardener who had apprenticed at one of the aristocratic estates there. The former President sought a Scotsman because he believed that “generally speaking, they are more orderly & industrious, than those of other nations,” and the climate in parts of Scotland was similar to that of Virginia. Washington’s letter to Anderson listed the skills he sought and summarized the responsibilities of Mount Vernon’s gardeners.

Wanted: A Good Kitchen and Nursery Gardener

A Gardener needed by George Washington, at Mount Vernon, Virginia, to start October 1797.

Responsibilities

- Maintains the pleasure grounds of a large plantation, including a formal garden, greenhouse, kitchen garden, and several lawns

- Oversees a workforce of two or three individuals and also labors in the garden himself

- Provides guests with tours of the grounds

Qualifications

- Capable of supplying sufficient fruits and vegetables to the table of a private residence with frequent visitors

- Experienced with growing exotic plants in a greenhouse and forcing plants in a hothouse

- Has successfully fulfilled the requirements of his apprenticeship

Benefits

- Salary of 20 to 25 guineas per year

- Passage to the United States if engaged for a period of three years

- He will be furnished with a good apartment convenient to his work

- If the applicant is single, the washing of his laundry is included

Based on George Washington’s letter to James Anderson, April 7, 1797

Preserving the Past

Today, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association strives to present the landscape as closely as possible to the way it appeared in 1799, the last year of George Washington’s life.

Unfortunately, there were no cameras to document the 18th-century layout, and until the advent of modern garden archeology, it was very difficult to determine the historical appearance of these spaces.

From the late 19th century, the upper garden was interpreted as a formal flower or rose garden with large and neatly trimmed boxwood hedges. In 2005, Mount Vernon archaeologists began an extensive dig searching for the upper garden’s historical appearance.

They located the remains of the broad walkways that Washington had installed as well as evidence for his six planting beds. These walkways lined up almost perfectly with those on the only known drawings of the landscape from Washington’s lifetime—those recorded by Samuel Vaughan in 1787. Our historians combed through Washington’s writings and those of his guests to determine what had been planted there. They also consulted garden manuals of the period and gardening practices at other estates to create a plan for the garden.

In 2011, the horticultural staff reinstalled the upper garden based on this extensive evidence, and today, the space is an accurate restoration of the garden George Washington created.

![By allowing viewers to see extended distances, spyglasses performed both aesthetic and practical functions. The standing man in Latrobe’s piazza scene peers toward the river – is he examining details of the carefully composed landscape, or searching for oncoming ships? Could this spyglass – thought to be one of several owned by George Washington – be the spyglass shown in the drawing? (MVLA, [W-644])](https://mtv-main-assets.mountvernon.org/files/styles/text_image_block/s3/callouts/sml_spyglass.jpg.webp?VersionId=MK__tdJ3vaelU1USWsohkFWYa.tyPKfl&itok=oyxdeBnU)

![George Washington's compass allowed him to lay out straight lines in his gardens and to determine boundaries for his surveys. The sights allow the user to determine the position of a line in relation to magnetic north. MVLA, Gift of Judge Charles Burgess Ball, 1876, [W-579/A-B]](https://mtv-main-assets.mountvernon.org/files/styles/text_image_block/s3/callouts/sml_surveying-gear-web.jpg.webp?VersionId=COSHLsfP5DNNHih03LVx_I6GFT9wmmoL&itok=Pc5EdPMB)

![New Principles of Gardening By Batty Langley London: A. Bettesworth et al., 1728, MVLA, Gift of Mrs. Fairfax Harrison, Vice Regent for Virginia, 1936 [M-1681]](https://mtv-main-assets.mountvernon.org/files/styles/text_image_block/s3/callout/text-image-block-full/image/sml_batty-langley-june-2013-shenk-103-web-3.jpg.webp?VersionId=JgIaNJiHk48_5hB975NX30gDo3roc.Rg&itok=YZ7cF3wg)