Get to know the Washington Library’s executive director, Patrick Spero.

In 2023, Mount Vernon was pleased to introduce a new executive director at the George Washington Presidential Library—Patrick Spero, Ph.D.

As an award-winning historian and former director of the Library & Museum of the American Philosophical Society, Dr. Spero is well-equipped to lead the Washington Library into its second decade, noting: “It is an incredible honor to serve as the next steward of the library. I am excited to grow its collections and develop new programs that expand knowledge of the life, leadership, and legacy of George Washington, the most important figure in the nation’s most important era.”

To mark this new era, sit a spell with Dr. Spero as he discusses his journey to Mount Vernon and why studying the life of George Washington is more important than ever.

For those meeting you for the first time, tell us a little about yourself. Where are you from, and when did you discover your passion for early American history?

I grew up in Sandwich, Massachusetts, the oldest town on Cape Cod. It was founded in 1637, and I spent a good part of my youth traveling to historic sites like Plimoth Plantation, Mystic Seaport, and all the sites in Boston. I think that visiting all these places made me realize how compelling the past could be—a fascinating mixture of being distant and different from my own time but also relatable and relevant.

Of course, I also remember the history homework assignment, I think in fifth grade, in which I was supposed to write a book review, and I did mine on the Journals of James Cook, which my father owned. The teacher didn’t believe I actually read it, but I now consider that my first real research project!

On your path to Mount Vernon, you were not only a student of history—you were an educator, serving on the faculty of Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. What was your biggest takeaway from your years at the front of the classroom?

I think one of the keys to being a professor is to be a translator, someone whose job it is to distill all the important work that scholars do and make it accessible and interesting for students. It’s a fun part of the job and something I still try to do now, just in different ways. I think most people have an inherent interest in the past, and whether as a professor or as a public historian, I see my job as better cultivating that interest through stories.

You’re coming to Mount Vernon after serving as Librarian and Director of the Library & Museum of the American Philosophy Society (APS), one of the nation’s most distinguished independent research libraries. What’s something most people don’t know about the APS?

Most people probably associate the APS with Benjamin Franklin (its founder) and early America, but it has over 14 million pages of manuscripts and its largest area of current collecting is in modern science. In fact, it has the papers of seven Nobel Laureates. I spent 10 years at the APS, first as a post-doctoral fellow surveying their early American materials and then as Librarian, and it was an incredible honor to steward that collection and spend a decade with Ben—but I am excited now to spend some time with George and learn about Mount Vernon’s incredible history.

What do you remember about your first visit to Mount Vernon?

I remember it distinctly. It was in 2007. I was a graduate student and had taken a job as a consultant on a project that was exploring the lives and legacies of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I stepped onto the estate knowing all that Washington did as Commander-in-Chief and as President, but I left the estate realizing that I actually didn’t really know Washington. He was far more complex than I realized. He was a scientist, innovator, entrepreneur, and civic leader. My trip to Mount Vernon, more than any book I had read, made me realize that I had a lot more to learn about him. I then dedicated myself to reading a lot of his letters and biographies, but there is still so much more for me to learn. I hope others who visit the estate have that same experience!

What attracted you to the George Washington Presidential Library?

Since it opened 10 years ago, I’ve watched with great admiration as the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Doug Bradburn as founding director, and Kevin Butterfield as my predecessor have established the George Washington Presidential Library as one of the premier centers for the study of the American Revolution and Founding. I cannot imagine a more exciting opportunity than to help the Library grow and evolve during its second decade.

Meet Patrick Spero, Executive Director of the Washington Library

Sit down with Patrick Spero as he discusses the legacy of George Washington and his vision for the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon.

Why do you think it’s so important that we continue to examine the life of George Washington?

Washington’s life is endlessly fascinating, and we are learning new things about it every day, often here on the estate itself through archaeology and historic preservation. There is so much more to him than I think most people realize. He was a pioneering farmer, an accomplished and well-regarded botanist who corresponded with leading scientists throughout Europe, an engineer who designed his own plow, a successful entrepreneur who was an early adopter of a new, more efficient mill, a large distiller, and he even created a large fishery that exported throughout the globe.

Above all else, though, Washington was, in my estimation, the nation’s greatest president, and not just because of all the precedents he set. He also faced tremendous challenges and a nearly endless stream of major crises that threatened the fragile foundations of the nation he was trying to build. He faced rebellions from within the country, threats from foreign nations trying to undermine American independence, the first party system, and conflicts on the high seas and the European and North American continents. It is not an overstatement to say that any misstep on any of these fronts could have ended the American experiment.

Sometimes I worry that Washington seems removed from issues that Americans face today and that perhaps more recent presidents, especially those who lived since the inventions of photographs and videos, resonate more. They might seem more relatable simply by being more visible. But Washington had to confront many issues that still animate our society today: whether it is about the national debt, the role of government in American life, the importance of supporting civic institutions to support society, or America’s role in the world. Studying Washington, and especially his management of these issues, is just as salient as a president whose tenure might be closer to our own time. He was able to accomplish a lot and survive these innumerable crises because he knew how to exercise political leadership in a democratic republic. He was a model of restraint and decisiveness, someone who knew when to wield power (or not) in order to strengthen the country at a time when it could easily have fallen apart.

As the Library marks its 10-year anniversary, what do you anticipate for the institution’s next 10 years?

A research library needs to do four things: collect material of enduring value, provide access to its holdings, support original research in it, and promote the work of scholars who are making new discoveries about the past.

There are lots of opportunities to enhance the already stellar work that the Library has been doing in each of these areas. For one, I have an aspirational goal that we can complete Washington’s book collection. Washington had over 1,000 books in his library, and his collection provides incredible insight into his intellect and thought. We have slowly been acquiring the books he actually owned along with what we call “matching editions”—a copy of the same edition of the books we know he owned. We have several hundred to go, and I think it would be fantastic to complete that project in the next 10 years.

The manuscripts at the Library are also remarkable, both those that related directly to Washington’s life as well as those that document the history of this historic site and its stewardship by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. So far, we have digitized a bit more than 8,000 items, which receive a notable amount of traffic—about 10,000 users a month, far more than we can serve in our reading room. Those 8,000 pages are just the tip of the iceberg, though, and their current use shows the large demand for this material. I believe that in the next 10 years, maybe even less, the Washington Library can make a concerted effort to digitize all of these items.

The Library hosts a robust fellowship program that brings scholars from across the world to Mount Vernon where they can ask new questions about our history and make original discoveries that change what we know about our past, help us understand our present, and shape our future. As support for the humanities and history wanes in so many sectors of our society, the GWPL can help sustain this vital work by providing more direct support for researchers who want to make these important contributions. Washington was himself a student of history, and he knew that a democracy was only as strong as its citizenry. While many critics of the American Revolution were sure that this experiment in democracy would turn into a tyranny, Washington believed that the greatest bulwark against these threats was through an educated citizenry. Mount Vernon can help fill this growing void and improve our nation’s poor historic literacy by increasing its direct support of historians whose work can inform our collective knowledge of the past and its lessons.

In that same vein, the Library has an obligation to share the work of the scholars who are making these contributions. The Library has been and needs to continue to be a convener of important conversations about the presidency, the Constitution, and civic education. With the approach of the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Washington Library has a central and vital role to play in organizing events to highlight the importance of the American Revolution, both in its own time and today. For Washington, the Revolution actually began in 1775, and, although independence was declared in 1776, that independence was not secured until 1783, so I see this anniversary, and the story it can tell, as one that continues past 2026.

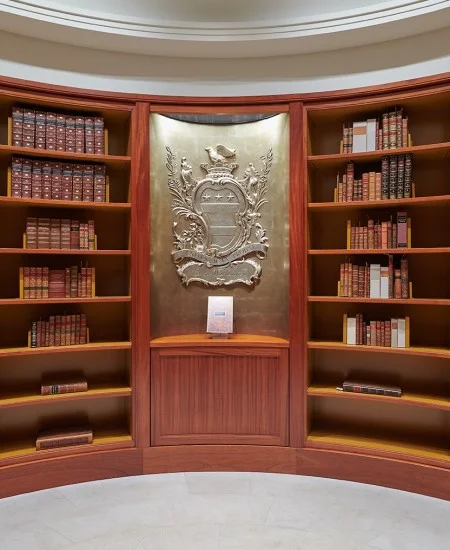

The Rare Books Suite includes an oval-shaped inner room that safeguards original books owned by George Washington, as well as duplicate editions of books from Washington’s library. The space also includes a six-foot-high pewter-toned rendition of Washington’s bookplate. (MVLA)

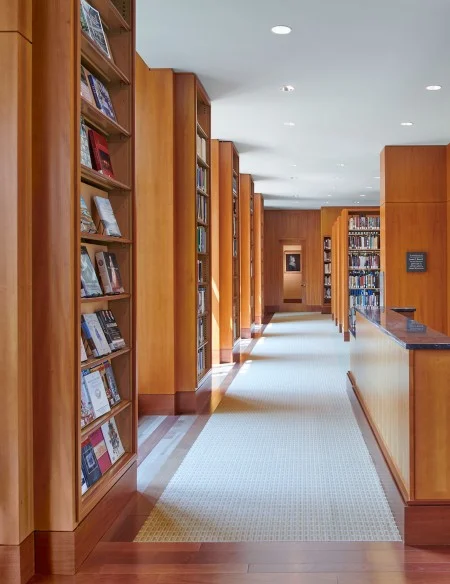

The Karen Buchwald Wright Reading Room is surrounded by six custom-created busts of prominent Framers as they would have appeared in 1785. (MVLA)

What’s your favorite place to visit on the Mount Vernon estate?

I have two. The first is the West Gate, which is the way most people in Washington’s time encountered the house. Unfortunately, it is not publicly accessible anymore, but the view of the estate from it is awe-inspiring. I often think: when someone first saw Mount Vernon from this perspective, what was Washington trying to project? When I look at it from this vantage point, I see some of Washington’s greatest attributes, a combination of power and restraint and of independence and order.

The other site is the slave quarters located just to the left of the Mansion. Today, this space tells so many interwoven stories about Mount Vernon and the nation, past and present. The first is the history of slavery on the estate itself, which is a hard conversation that is important to have. These rooms and their exhibits also provide a small window into the daily lives of the enslaved and help contextualize their experiences. The other is the story of the building itself. It is a replica that was built after WWII. The bricks used for it came from the White House, which was itself going through its own renovation. So, when you are standing inside these reconstructed slave quarters, the bricks that surround you are the same ones that surrounded Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Abraham Lincoln, and so forth—and we have discovered that these bricks were forged in a kiln in Alexandria that relied on enslaved labor. Standing inside that building, it is hard to wrap my head around all the history and stories that combine in that one space.