The story of slavery at Mount Vernon is complex and painful. But it is also a story of strength, humanity, and hope.

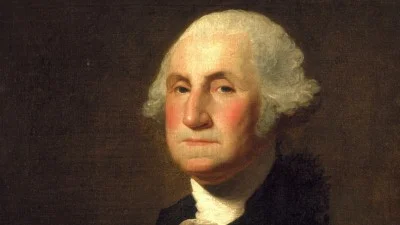

Mount Vernon was the home of George Washington. It was also home to hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children who lived here under Washington’s control. He depended on their labor to build and maintain his household and plantation. They, in turn, found ways to survive in a world that denied their freedom.

Where did Mount Vernon’s enslaved people come from?

Most were born at Mount Vernon or other plantations in Virginia—in some cases to families that had been enslaved in the American colonies for generations.

Others were captured in Africa. Depending on which ships transported them and when they arrived, people imported to Virginia came from different regions of the African continent, including Senegambia, the Bight of Biafra, and West Central Africa.

Slavery and the Washingtons' World

Like most elite Americans, the Washingtons were deeply entangled in a global commercial system that revolved around slavery. The vast network of 18th-century transatlantic trade involved the flow of manufactured goods from Europe, enslaved people from Africa, and raw materials from the Americas.

At Mount Vernon, Washington used enslaved labor to catch fish and grow crops like tobacco and wheat. He shipped these commodities to Europe and the Caribbean for sale in exchange for luxury goods and exotic products. Mahogany furniture, silver candlesticks, Chinese porcelain, silk textiles, crates of limes, and casks of rum signaled Washington’s wealth and gentility.

Within the world of the Mount Vernon Mansion, George and Martha Washington relied on enslaved people to operate their household. Frank Lee, Caroline Branham, Doll, and other domestic workers toiled long hours without pay to clean the Washingtons’ rooms, launder clothes, prepare meals, and wait on guests. Their daily labor brought them into contact with the elegant furnishings. These objects were polished, dusted, filled, emptied, and moved by Mount Vernon’s enslaved laborers, who were legally considered property themselves.

"And I do…most pointedly, and most solemnly enjoin it upon my Executors... to see that this clause respecting Slaves…be religiously fulfilled… without evasion, neglect or delay."

- George Washington's Last Will and Testament, July 9, 1799

Learn MoreWashington and Slavery

In 1732, the year of George Washington’s birth, slavery was legal everywhere in the Atlantic World. The economy and social structure of Washington’s native Virginia depended on the labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants to cultivate cash crops like tobacco.

Slavery was an integral part of Washington’s life from an early age. At age 11, he inherited 10 enslaved people from his father. He would go on to inherit, purchase, rent, and gain control of more than 500 enslaved people at Mount Vernon and his other properties by the end of his life.

Washington's Changing Views

Washington’s views on slavery changed over time. Economic and moral concerns led him to question slavery after the Revolutionary War, though he never lobbied publicly for abolition. Unable to extricate himself from slavery during his lifetime, Washington chose to free the 123 enslaved people he owned outright in his will. He was the only founding father to do so.

“The unfortunate condition of the persons whose labour in part I employed, has been the only unavoidable subject of regret.”

- George Washington, ca. 1787-1788

Life of the Enslaved

The men, women, and children enslaved on George Washington’s estate had little control over their lives. Their unpaid labor in Mount Vernon’s fields, workshops, and Mansion kept the estate running and supported the Washingtons’ elite lifestyle. Considered property by law, enslaved people had no legal rights and little personal autonomy. They could be sold or separated from family members at any time.

Life is a burden to a slave person, indeed it is–left without education and the mind terrified all the time.

- Edmund Parker, 1898

As they faced lives in bondage, Mount Vernon’s enslaved people showed strength and resilience. They formed families, created tight-knit communities, found ways to earn money, acquired personal possessions, and resisted the bonds of slavery.

Most enslaved people never had the opportunity to become literate and left no written documents. Information about their lives must come from other sources. Washington’s records, archaeology, and oral histories from descendants can help us reconstruct the lives of Mount Vernon’s enslaved people.

Daily Life

Most enslaved people never had the opportunity to become literate and left no written documents. Information about their lives must come from other sources. Washington’s records, archaeology, and oral histories from descendants can help us reconstruct the lives of Mount Vernon’s enslaved people.

"Riots, routs, unlawful assemblies, trespasses, and seditious speeches by a slave or slaves, shall be punished with stripes."

- An Act Concerning Slaves, 1785

What did it mean to be enslaved in 18th-century Virginia?

By 1799, the last year of George Washington’s life, slaves made up nearly 40 percent of Virginia’s residents. To prevent the enslaved population from rebelling, white lawmakers passed a series of “slave codes” governing the status, rights, and treatment of those in bondage. Violators faced severe punishment, including whipping, branding, and maiming.

The laws stipulated that:

Slaves were property, not people.

They could be bought, sold, rented, and inherited, just like houses, furniture, or livestock. If a master killed his slave in the course of punishment, there were no legal consequences.

Enslavement was permanent.

Unlike indentured servants, who became free after a set period of time, enslaved people were in bondage for life unless their owner chose to free them. Prior to 1782, emancipation in Virginia required special permission of the legislature, so it rarely occurred.

Enslavement was hereditary.

A child born to an enslaved woman was a slave from birth.

Enslaved people had no legal rights.

They could not vote, appear in court, or enter into contracts. They could not leave their plantation without written permission from an owner or overseer. Laws prevented enslaved people from gathering in large groups.

They could not legally marry

...and could be separated from family members at any time. While George Washington recognized marriages between enslaved people, these unions had no legal standing.

Mount Vernon after 1799

After Martha Washington’s death in 1802, the property passed to her late husband’s heirs.

Learn more

The content on this page was adapted from Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, an exhibition on view from 2016–2020.

In 2025, Mount Vernon opened a reimagined version of the Lives Bound Together exhibition within the historic greenhouse quarters.