A staff of enslaved butlers, housemaids, waiters, and cooks made the Washingtons’ lifestyle possible.

I beg you will make Caroline put all the things of every kind out to air and Brush and Clean all the places and rooms that they were in…

- Martha Washington to her niece, 1794

Their daily labor brought them into frequent contact with the home’s furnishings. Many objects in Mount Vernon’s collection were touched by enslaved people as much—if not more—than by the Washingtons themselves.

Caroline Branham

Caroline Branham, an enslaved housemaid, was about 35 years old in 1799. She began her work before sunrise and finished after sundown each day.

House Bell

This metal bell belonged to Mount Vernon’s original house bell system, installed in the 1780s. A series of wires, cranks, and pins connected pulls in the dining room and bedrooms to bells affixed to an outside wall. The bell’s “ding” alerted enslaved laborers in the Mansion area that they were wanted. Those who worked in the house were always on call.

Argand Lamp

Enslaved housemaids were responsible for tending to the fires, candles, and oil lamps that served as Mount Vernon’s only artificial light sources. Argand lamps like this were cutting-edge technology in the 1790s, designed to maximize brightness and minimize smoke.

Jug and Basin

Mount Vernon residents used long-necked jugs and basins in their bedchambers to wash their faces, necks, and hands—the typical daily hygiene of the era. Housemaids filled the jugs and later emptied dirty water from the basins.

Personal Attendants

Some enslaved people were intimately involved in the Washingtons’ daily lives. Valets, chamber maids, and nannies helped their masters and mistresses dress and bathe, arranged their hair, cleaned and mended their clothes, and delivered their messages.

The Washingtons relied on this labor and grew attached to the servants they interacted with frequently. The feeling may not have been mutual. Several enslaved domestic workers tried to escape, including Martha’s maid Ona Judge (who succeeded) and George’s valet Christopher Sheels (who didn't).

William (Billy) Lee

William Lee arrived at Mount Vernon in 1768, after Washington purchased him from a wealthy Virginia widow for 61 pounds and 15 shillings. Lee served as Washington’s valet for over 20 years, accompanying him everywhere. After severe knee injuries limited his mobility, Lee was reassigned to work as the estate’s shoemaker.

“We had an exceeding good Dinner, which was served up in excellent order.”

- Olney Winsor, Mount Vernon Visitor, 1788

Dining at Mount Vernon

The Washingtons relied on enslaved butlers, cooks, waiters, and housemaids to support their daily meals and frequent dinner parties. The family typically ate two substantial meals per day—breakfast at 7 a.m. and dinner at 3 p.m. Tea or coffee sometimes followed in the early evening.

At Mount Vernon, enslaved butler Frank Lee supervised preparations for the Washingtons’ meals, sometimes in conjunction with a hired white housekeeper. Lee ensured that the enslaved waiters and housemaids set the table properly with an elaborate array of porcelain dishes, glasses, silverware, and decorative ornaments. When the cooks had finished preparing the food, waiters carefully transported heavy platters from the detached kitchen to the dining room.

During the meal, waiters in white-and-red livery suits stood silently against the walls, ready to refill wine glasses or pass serving dishes. When the diners had finished, Frank Lee oversaw as the waiters and housemaids cleared the table, shook out table linens, swept up crumbs, took dishes to be washed by the cook’s assistant, polished silver, and returned tableware to storage.

Frank Lee

As butler, Frank Lee was often the first person visitors to the Mount Vernon Mansion encountered. Described as “portly, polite, and most accomplished,” he played a vital role in managing the household. On the inventory of the Mansion taken after Washington’s death, the pantry near the dining room was called “the closet under Frank’s direction.”

Outdoor Dining

The Washingtons used Mount Vernon’s piazza as an outdoor parlor in the hot summer months. To transform the space, enslaved workers moved a table from the house onto the piazza’s flagstone floor. They also carried out the hot water urn and tableware (see below) for coffee or tea.

Reading Between the Lines: A Guest for Coffee

Slavery made the Washingtons’ famous hospitality possible. After retiring from the presidency, George Washington hosted more than 650 overnight stays in one year. Visitors meant extra duties for enslaved cooks, waiters, housemaids, and grooms. English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe visited in July 1796. His diary entries suggest the many tasks the estate’s enslaved workers performed.

"Having alighted, I sent in my letter of introduction and walked into the portico next to the river."

Though not an invited guest, Latrobe brought a letter of introduction from George Washington’s nephew Bushrod. He probably handed it to the butler, Frank Lee.

"Dinner was served up about 1/2 after three."

Enslaved cooks Hercules and Lucy prepared the meal. Frank Lee, along with waiters Marcus and Christopher Sheels, served the family and guests at the table.

"Coffee was brought, about 6 o’clock."

Latrobe made several sketches of the Washingtons enjoying coffee on the piazza. One shows an enslaved man, possibly Frank Lee, standing behind the table. This figure is missing from Latrobe’s final watercolor of the scene.

Latrobe’s sketch of the piazza. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, 1960.108.1.2.21.

"We soon after retired to bed."

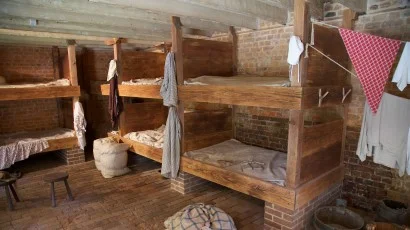

A housemaid, possibly Caroline Branham or Charlotte, prepared Latrobe’s room, ensuring the bed had fresh linens, filling a jug with clean water for washing and, if needed, emptying his chamber pot the next morning.

“…the horses came to the door.”

Cyrus or Wilson, Mount Vernon’s grooms, likely cared for Latrobe’s horses, boarding them in the stable overnight and bringing them back to the house for his departure.

Cooking at Mount Vernon

Cooking in Mount Vernon’s kitchen was hot, smoky, demanding, and skilled work. Enslaved cooks like Doll, Hercules, Nathan, and Lucy arose at 4 a.m. each morning to light the fire in the oven and prepare for the meals to be served in the Mansion. Their duties could continue well into the evening. The Washingtons placed great trust in their cooks, whose talent was evident in visitors’ descriptions of sumptuous meals.

Under Martha Washington’s supervision, cooks planned menus and selected ingredients for each day’s meals. Enslaved laborers on the estate grew and harvested most of the Washingtons’ food: wheat and corn from the fields, fresh vegetables from the garden, fruit from the orchards, fish caught in the Potomac, and smoked ham from hogs raised on site. Imported luxuries like tea, coffee, chocolate, olives, oranges, and wine supplemented homegrown ingredients.

Their role in the kitchen allowed enslaved cooks to shape the tastes of the household—and the region. Many iconic Southern dishes bear the influence of West African cuisine, from stews like gumbo to ingredients like okra, sweet potatoes, peanuts, and collard greens.

18th-Century Waffle Iron

Purchase, 1939 [W-1057]

Doll

Doll was 38 years old when she arrived at Mount Vernon in 1759 as part of Martha Washington's “dower” share of her first husband’s estate. She served as the Washingtons’ cook until the 1780s, preparing countless meals for the family and their guests.

Hercules

As chef at the executive residence in Philadelphia, Hercules produced elaborate meals for the Washingtons, members of Congress, and foreign dignitaries. Described as a “celebrated artiste,” he became a well-known figure in the city. He escaped from Mount Vernon in 1797 and was never recaptured.

A Day in the Life of an Enslaved Cook

Cooks were expected to be in the kitchen by 4:30 a.m. to begin preparing the Washingtons' breakfast and often did not finish their work until 8 p.m.

Learn more

The content on this page was adapted from Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, an exhibition on view from 2016–2020.

In 2025, Mount Vernon opened a reimagined version of the Lives Bound Together exhibition within the historic greenhouse quarters.