George Washington traveled extensively within the boundaries of the British Empire in North America and United States, though only went abroad once in his lifetime. Washington traversed through most of the what became the early United States, stretching north to New England, south to Georgia, and as far west as the Ohio Valley. In the course of his travels Washington met a variety of people. He visited and lodged with people who spoke English, German, and several Native American languages. His accommodations and travels taught him much about what would become the United States.

Travel as a Surveyor

As a trained surveyor, Washington knew his local landscape in Virginia well. He took his first significant trip in 1748, when at the age of sixteen he was invited to accompany a surveying party to assess land in the western part of Virginia belonging to Thomas, Lord Fairfax.1 At this point in his life, Washington became increasingly interested in landed opportunities to the west, remarking on the natural richness of western Virginia and areas that would later be a part of present-day West Virginia.

Travel to Barbados

Washington accompanied his ill, half-brother Lawrence Washington to Barbados in 1751 in hopes of seeking relief for his tuberculosis. This was his only time travelling abroad, but he was exposed to social experiences such as the theater that had a lasting impact on his life.2 While there he also studied and documented various wildlife features.3 He returned home with coral from the island that he displayed at Mount Vernon. Importantly, while visiting, George Washington suffered and survived from smallpox. This exposure allowed him to develop immunity from the illness during the American Revolution. When the brothers returned to Virginia, Lawrence passed away in July of 1752.

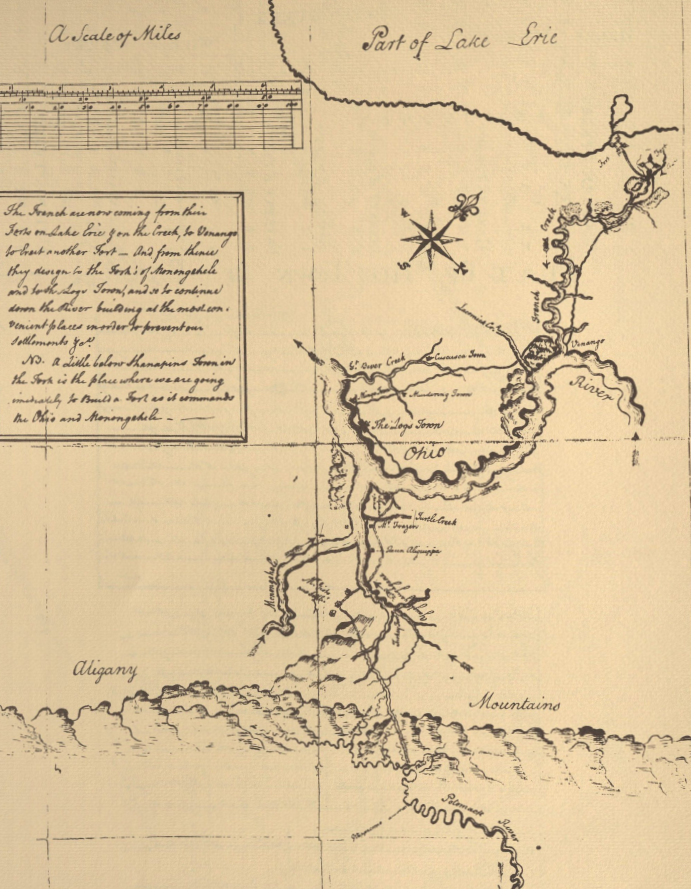

Travel as a Soldier

As a surveyor and soldier, Washington moved throughout western lands located in the present-day states of Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.4 Washington travelled to present-day Pittsburgh on the Alleghany Expedition in 1753, to Ohio on the Braddock Expedition in 1755 and to the Ohio River Valley on the Forbes Expedition in 1758. During these missions a part of the Seven Years’ War in North America, Washington interacted with French soldiers, foreign translators, and Indigenous people. Most notably, he negotiated with Tanacharison “Half-King” a Seneca leader who also recalled his nation’s dealings with his great-grandfather John Washington.

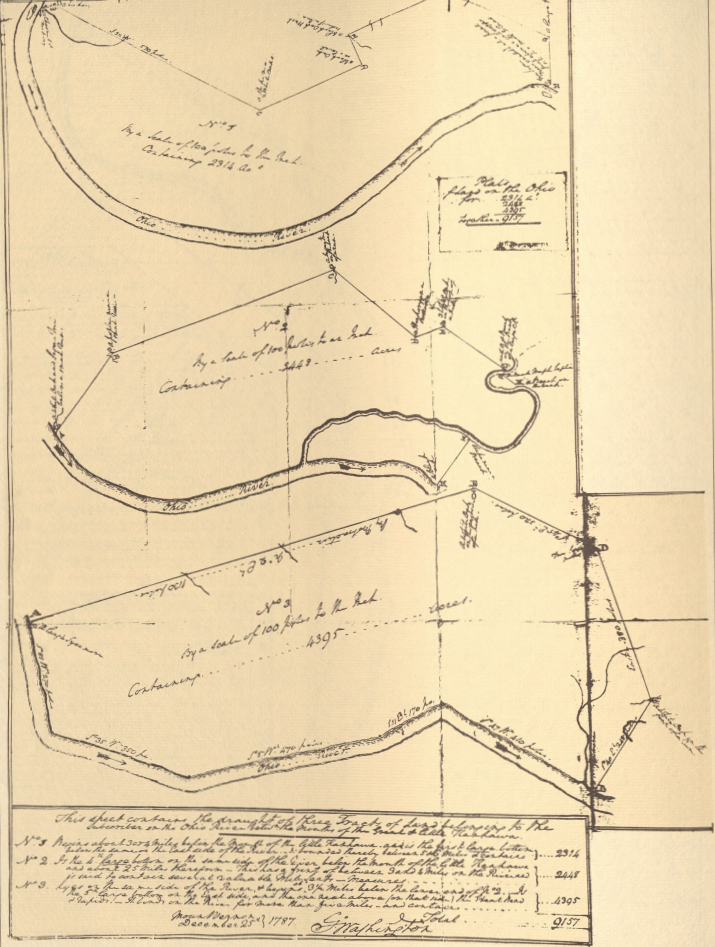

Washington received notoriety for documenting his time as a solider through his publication, The Journal of Major George Washington documenting his experiences on the Alleghany Expedition.5 Additionally, for his service, Washington was entitled to western lands, including on the Ohio River Valley such as on the Kanawha River. He used his parcels received for his service to continue to speculate nearby land, often buying parcels from other soldiers who did not desire the land. His land speculation continued all the way to land purchases in present-day Kentucky.

Travel After Marriage

Washington's 1759 marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis led to less constant travel, however his attendance at the twice-yearly sessions of the House of Burgesses provided more than a decade of experience navigating between Mount Vernon and the colonial capital of Williamsburg. Washington began traveling again in the 1770s, beginning with a trip to the western lands with his friend, Dr. James Craik.6 They later returned to those lands in 1784, after the American Revolution.

Travel and the American Revolution

In 1774 and 1775 Washington visited Philadelphia as part of the Virginia delegation to the First and Second Continental Congresses.7 As commander of the Continental Army between 1775 and 1783, Washington traveled throughout multiple states and established various headquarters including at Cambridge, Valley Forge, Morristown, and Newburgh. During the course of the war he travelled as far as New York to Yorktown, Virginia. He only briefly stopped at Mount Vernon while travelling to Yorktown. He coordinated the travel of Martha Washington to meet him at various headquarters.

After the war and his final journey west in 1784, Washington believed he perhaps returned to Mount Vernon to spend most of his life. However, three years later Washington was enticed away from Mount Vernon, back to Philadelphia in 1787 to preside over the Constitutional Convention.8 It was there he was seen as the obvious choice for the nation’s first president.

Travel as the President

In 1789, Washington traveled to New York for his inauguration as the country's first president, and later to Philadelphia when the capital was relocated there. At both capitals, Washington and his family enjoyed activities like the theater and circus. Living in these cities connected him to other government officials, foreign ambassadors, and friends from the American Revolution.

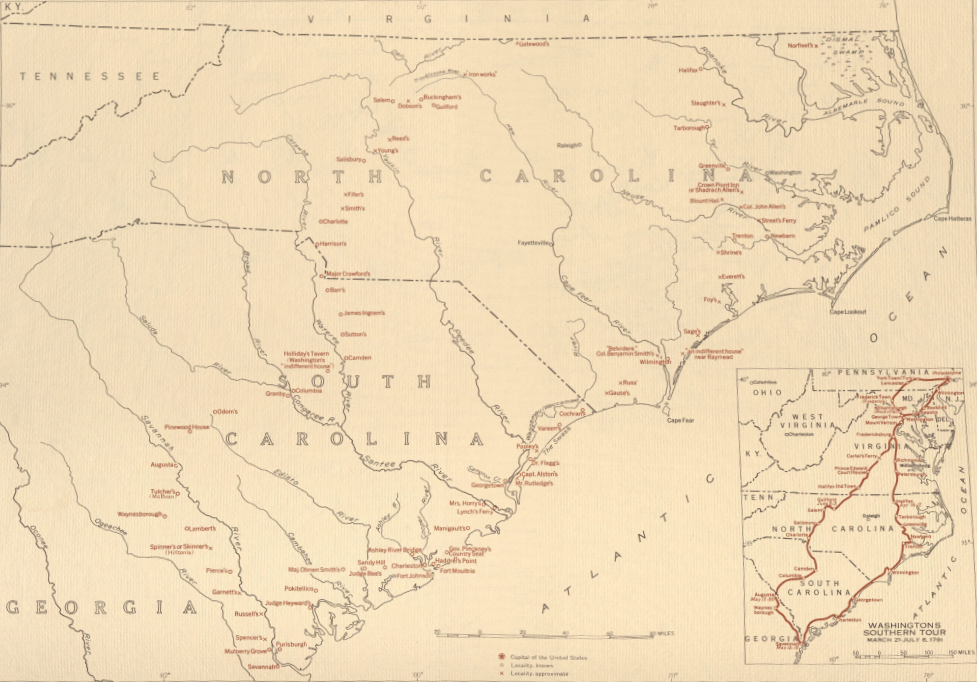

Washington wanted to learn as much as he could about the United States and its people. As a result, he made three presidential tours: to New England in 1789, Long Island in 1790, and to the southern states in 1791.9 In doing so, Washington visited the first thirteen states. Washington was greeted with hospitality, parades, and communities organized improvements to roads and bridges to ensure the ease of his travel. In the latter part of Washington's life people along the route of his journeys frequently wanted to celebrate his arrivals and departures. The President's arrival in Annapolis, Maryland, during his Southern Tour was announced by the firing of fifteen guns, a greeting by the governor, and two official dinners—one at the governor's home and the other for the town’s citizens.10

Washington's diary indicates that he had a preferred travel routine. Washington tended to get an early start and then stop along the road at a tavern for breakfast. Continuing his journey, he would break again for dinner in the afternoon only to stop to rest during the evening. Washington liked to travel at a fairly quick pace, noting in his journal that his "usual travelling gate" was "5 Miles an hour."11

Shortly after Washington's retirement from the presidency his step-granddaughter Nelly described the trip home to Mount Vernon to a friend as being "tedious & fatiguing."12

However, the family had clearly become adjusted to all the ceremony in their lives, accurately illustrating Washington's arc to social and political prominence: "We encountered no adventures of any kind, & saw nothing uncommon," Nelly explained, "except the light Horse of Delaware, & Maryland, who insisted upon attending us through their states, all the Inhabitants of Baltimore who came out to see, & be seen & to Welcome My Dear Grandpapa—some in carriages, some on Horseback, the others on foot."13

Following his presidency Washington retired once more to Mount Vernon but was forced to leave for Philadelphia one last time in 1798 when war with France became a possibility. After that brief trip, he returned to Mount Vernon where he would spend the remainder of his life. The nature, extent, and reaction to Washington's travels changed, reflecting the larger shifts in his public life and his own interests.

Revised by Zoie Horecny, Ph.D., 11 August 2025

Notes:

1. The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, (Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1976-1979), 1-23.

2. “[Diary Entry: 14 November 1751],” Alicia K. Anderson, Lynn A. Price, William M. Ferraro, eds., George Washington’s Barbados Diary, 1751-1752. University of Virginia Press, 2018, pg. 70.

3. “[Diary Entry: 22 December 1751],” Alicia K. Anderson, Lynn A. Price, William M. Ferraro, eds., George Washington’s Barbados Diary, 1751-1752. University of Virginia Press, 2018, pg. 77.

4. The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1, ed. by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, (Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1976-1979), Vol. 1, 118-210

5. “Journey to the French Commandant: Narrative,” Founders Online, National Archives.

6. For the western trip, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 4, 1-71.

7. For Washington's activities during the 1st and 2nd Continental Congresses, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 3, 272-288, 327-36.

8. For the Constitutional Convention, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 5, 153-87.

9. On Washington's New England Tour, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 5, 460-497. For his tours of Long Island and the Southern states, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 6, 62-7, 96-169.

10. "Eleanor Parke Custis to Elizabeth Bordley, 18 March 1797," George Washington’s Beautiful Nelly: The Letters of Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, 1794-1851, ed. Patricia Brady (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1991), 30-1.

11. See diary entry for 12 September 1784, in The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 4, 19.

12. For the trip home to Mount Vernon after his retirement, see The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 6, 236-9.

13. "Eleanor Parke Custis to Elizabeth Bordley, 18 March 1797," George Washington’s Beautiful Nelly: The Letters of Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, 1794-1851, ed. Patricia Brady (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1991), 30-1.

Bibliography:

Abbot, W.W. "George Washington, the West, and the Union." Indiana Magazine of History 84 (March 1988): 3-14.

Atkinson, Rick. The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777. Henry Holt and Company, 2019.

Atkinson, Rick. The Fat of the Day: The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780. Crown, 2025.

Anderson, Alicia K., Lynn A. Price, William M. Ferraro, eds., George Washington’s Barbados Diary, 1751-1752. University of Virginia Press, 2018.

Achenbach, Joel. The Grand Idea: George Washington's Potomac and the Race to the West. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002.

Breen, T. H. George Washington: The President Forges a New Nation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life. New York: The Penguin Press, 2010.

Cleland, Hugh. George Washington in the Ohio Valley. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1955.

Cook, Roy Bird. Washington’s Western Lands. Strasburg, Va.: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc., 1930.

Ferling, John. The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009.

Henderson, Archibald. Washington's Southern Tour. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1923.

Hughes, Sarah. Surveyors and Statesmen: Land Measuring in Colonial Virginia. Richmond: Virginia Surveyors Foundation and Virginia Association of Surveyors, 1979.

Lipscomb, Terry W. South Carolina in 1791: George Washington’s Southern Tour. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1993.

Maass, John R. From Trenton to Yorktown: Turning Points of the Revolutionary War. New York, NY: Osprey Publishing, 2025

McDonnell, Michael A. Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America. New York: Hill and Wang, 2015.